More Than a Gathering: Lammii gathering of Buundhaa in Boji Becomes a Hub for Oromo Cultural Revival

Subtitle: Lammii gathering of Buundhaa from Across the Region Unite on the Pitch, Spark Community Dialogue on Aadaa and Safuu

BOJI, OROMIA — The sound of cheering fans and bouncing footballs has become a powerful call to unity in the rural landscape of Boji. Here, at the Ambo Ejersa gathering, a simple cultural gathering event has blossomed into a profound social gathering, uniting Oromo generations from various parts of the country and reigniting vital conversations about cultural heritage and values.

The generation gathering has successfully drawn teams that map the Oromo heartland: local generation from Boji are competing alongside their brothers from Itaya, Ambo, Meexxii, Maatii, Wadesse, and Shanan. This convergence on the lammii pitch represents a significant grassroots effort to strengthen communal bonds that stretch across the region.

“This is truly something that brings joy,” remarked an elderly spectator, Bulo Tadese, his eyes following the energetic play. “In these times, seeing our sons from different corners come together in peace and healthy competition… it warms the heart. Waan haalan nama gammachisudha (It is profoundly joyous).”

Yet, the true significance of the event extends far beyond the final score. In the shade of trees and under makeshift tents, the community surrounding the gathering is engaging in a parallel, equally important contest: a collective effort to reclaim and revive core Oromo principles.

During breaks and after matches, elders, players, and spectators are gathering for marii boonsaa—meaningful, extended community dialogues. The central focus is the urgent discussion of aadaa (culture/tradition) and safuu (a deep-seated moral and ethical code governing respect and social harmony).

“This lammii gathering of Buundhaa was the spark, but the conversation is the real fire,” said organizer Dhaqaba Gammada. “We play the meeting to bring the generation of Buundhaa together, but we use this gathering to ask important questions: How do we preserve our identity? How do we practice safuu in our daily lives? The energy here shows our people are hungry for this discussion.”

The spontaneous emergence of these dialogues points to a deep-seated community desire to navigate modernity while firmly rooting the younger generation in their cultural foundation. Elders see it as a chance to impart wisdom, while youth see it as a space to understand their heritage in a contemporary context.

The Ambo Ejersa lammii gathering of Buundhaa stands as a powerful example of how lammii gathering can serve as a catalyst for social cohesion and cultural preservation. It demonstrates that the goal is not only to win games but to strengthen the very fabric of the community, ensuring that the values of aadaa and safuu are passed on, debated, and lived.

As the lammii gathering of Buundhaa continues, the message is clear: the most important victory is happening off the field, in the hearts and minds of a people rediscovering the strength of their shared identity.

Galma Araaraa: A Spiritual Journey of the Oromo People

A ceremony of reconciliation, peace, and renewal marks a profound cultural resurgence for the people of East Shewa.

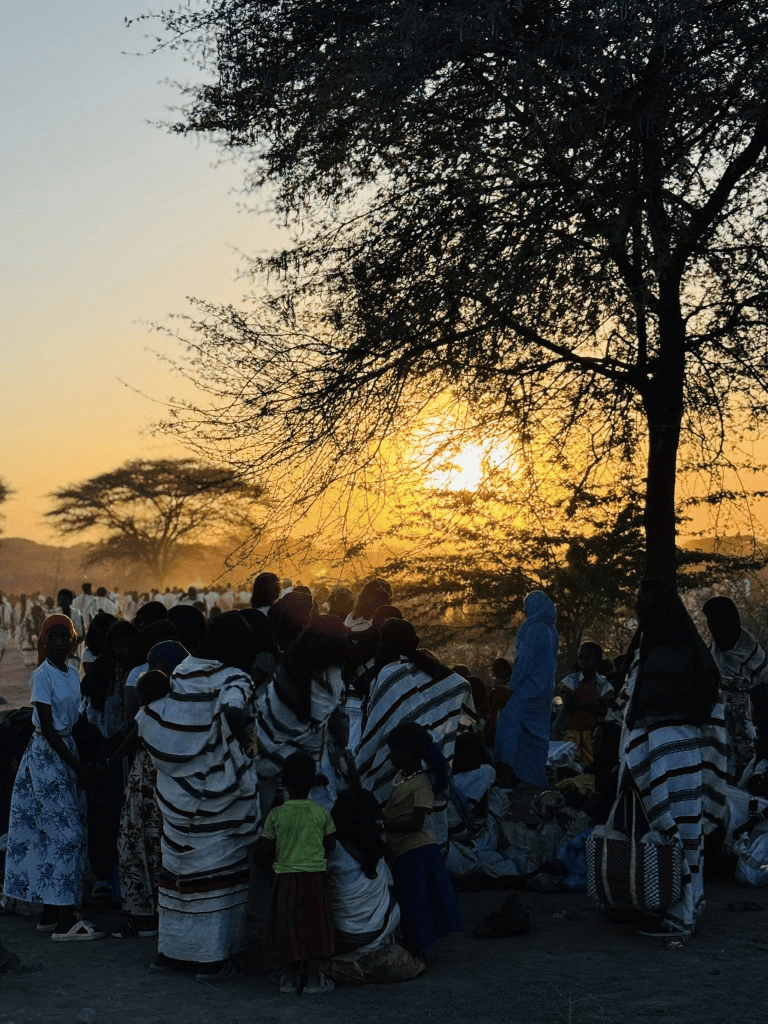

DIRREE BADHAAS, OROMIA – In a powerful display of cultural and spiritual revival, the Waaqeffannaa community recently conducted the sacred Galma Araaraa (House of Reconciliation/Restoration) ritual within the revered Dirree Badhaas ritual ground. This profound ceremony, described by participants as a monumental sign of reclaiming their ancestral identity, wove together deep spiritual homage, ecological connection, and intergenerational transmission.

The Galma Araaraa was enacted as a multifaceted ritual of restoration. It began with devoted prayers to Waaqa (the Supreme Being) at the site, followed by rituals performed within the surrounding natural landscape (duudhaa gaa’elaa), emphasizing the inseparable bond between the community, their spirituality, and their environment.

A central and hopeful aspect of the gathering was the active involvement and education of the younger generation (dhaloota haaraa), ensuring the continuity of this sacred knowledge and practice. The rituals culminated in community-wide celebrations featuring traditional songs of blessing (qabbanaa) and joyous dances (marabbaa), transforming the site into a vibrant hub of collective expression.

Elders and spiritual leaders present articulated that the Galma Araaraa served a higher purpose than a single event. It was, they stated, a deliberate act of constructing five essential spiritual houses: a House of Peace (galma nagaa), a House of Joy (galma gammachuu), a House of Resolution (galma furmaataa), a House of Motivation (galma dammaqiinsaa), and a House of Unity (galma waloomaa).

“The successful completion of this Galma Araaraa on our ancestral land of Dirree Badhaas is our greatest sign (mul’ata keenya guddaa),” declared one senior Qallu. “It signifies the return of our people to the dignity and fullness of our original identity (eenyummaa duriitti deebisu). This is a journey of spiritual homecoming.”

The event has been hailed by cultural observers as a significant step in the preservation and revitalization of indigenous Oromo spiritual heritage, demonstrating its enduring role in fostering social harmony, environmental stewardship, and cultural pride.

Revival of Sirna Goobaa: A New Dawn for Oromo Governance

Feature News: Dawn Reclamation – Oromo Gadaa Assembly Ushers in New Era at Historic Tarree Leedii Site

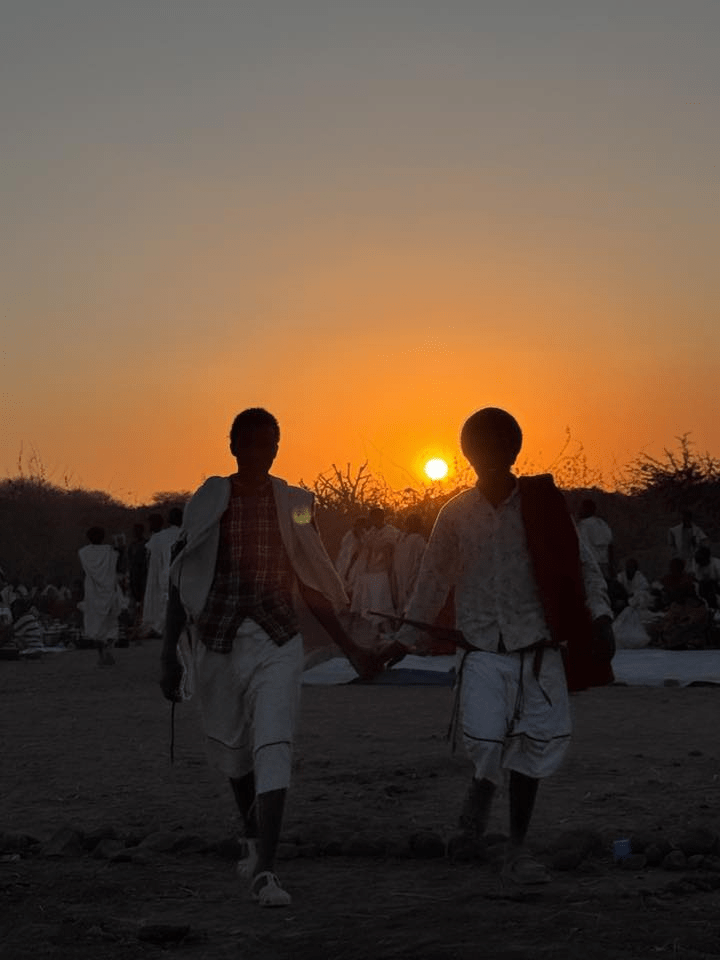

FANTAALLEE, SHAWA BAHAA, OROMIA – In a powerful act of cultural restoration and communal resolve, the Oromo Gadaa system of the Karrayyuu region has formally reinstated its traditional assembly, the Sirna Goobaa, at the sacred grounds of Ardaa Jilaa, Tarree Leedii. This landmark gathering, conducted at dawn on Saturday according to sacred custom, marks not just a meeting, but the revival of an ancient democratic and spiritual heartbeat in Eastern Shawa.

The ceremony, led by Abbaa Gadaas, elders, and community representatives, began in the pre-dawn hours, adhering strictly to the profound rituals and aesthetics of Oromo tradition. Participants gathered under the ancient trees of Ardaa Jilaa, a site long held as a seat of ancestral wisdom and collective decision-making, to reignite the principles of the Sirna Goobaa—the assembly of law, justice, and social order.

“This is not a symbolic gesture; it is a homecoming,” declared one senior elder, his voice echoing in the crisp morning air. “We are reclaiming our space, our process, and our responsibility to govern ourselves according to the laws of our forefathers and the balance of nature. The Goobaa is where our society heals, deliberates, and progresses.”

The choice of location and time is deeply significant. Tarree Leedii is historically a cornerstone of socio-political life for the Karrayyuu. By convening at dawn (ganamaa), the assembly honors the Oromo cosmological view that links the freshness of the morning with clarity, purity, and the blessing of Waaqaa (the Supreme Creator). The meticulous observance of rituals involving sacred items, chants (weeduu), and the pouring of libations underscores a commitment to authenticity and spiritual sanction.

Community members, young and old, observed in reverent silence as the protocols unfolded. For many youth, it was a first-time witnessing of the full, unbroken ceremony. “To see our governance system in action, here on this land, is transformative,” said a young university student in attendance. “It connects the history we read about directly to our future. It shows our systems are alive.”

The reinstatement of the Sirna Goobaa at Ardaa Jilaa sends a resonant message beyond the borders of Fantuallee District. It represents a grassroots-driven renaissance of indigenous Oromo governance, asserting its relevance and authority in contemporary community life. It serves as a forum to address local disputes, environmental concerns, and social cohesion through the framework of Gadaa principles—Mooraa (council), Raqaa (law), and Seera (covenant).

Analysts view this move as part of a broader movement across Oromia where communities are actively revitalizing Gadaa and Waaqeffannaa institutions as pillars of cultural identity and self-determination. The successful convening at Tarree Leedii demonstrates local agency and the enduring power of these systems to mobilize and inspire.

As the sun rose over the assembly, illuminating the faces of the gathered, the event concluded with a collective affirmation for peace, justice, and unity. The revival of the Sirna Goobaa at this historic site is a dawn in every sense—a new beginning for community-led governance, a reconnection with ancestral wisdom, and a bold statement that the Gadaa of the Karrayyuu is once again in session, ready to guide its people forward.

Oromo New Year Birboo: Tradition and Unity in Waaqeffannaa Faith

Feature News: Celebrating Heritage and Harmony – Waaqeffannaa Faithful Usher in Oromo New Year 6420 at Walisoo Liiban Temple

WALISOO LIIBAN, OROMIA – In a profound celebration of cultural rebirth and spiritual unity, the Waaqeffannaa faithful gathered at the sacred Galma Amantaa (House of Worship) here on Thursday to solemnly and joyfully observe the Oromo New Year, Birboo, marking the dawn of the year 6420.

The ceremony was far more than a ritual; it was a powerful reaffirmation of an ancient identity, a prayer for peace, and a community’s declaration of continuity. Under the sacred Ficus tree (Odaa) that stands as a central pillar of the Galma, elders, families, and youth came together in a vibrant display of thanksgiving (Galata) to Waaqaa (the Supreme Creator) and reverence for nature and ancestry.

The air was thick with the fragrance of burning incense (qumbii) and the sound of traditional hymns (weeduu) as the Qalluu (spiritual leader) guided the congregation through prayers for blessing, prosperity, and, above all, peace for the coming year. The central message of the celebration, as echoed by the organizers, was a heartfelt benediction for the entire Oromo nation: “May this New Year bring you peace, love, and unity!” (Barri kun kan nagaa, jaalalaafi tokkummaa isiniif haa ta’u!).

This public and dignified observance of Birboo carries deep significance in the contemporary context of Oromia. As Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group navigates complex social and political landscapes, the celebration at Walisoo Liiban served as a potent symbol of cultural resilience.

“Observing Birboo at our Galma is not just about marking a calendar,” explained an elder attending the ceremony. “It is about remembering who we are. It is about connecting our past to our future, grounding ourselves in the values of balance, respect for all creation, and community that Waaqeffannaa teaches. In praying for peace, we are actively willing it into being for our people.”

The sight of children learning the rituals and youths actively participating underscored a vital theme: the intergenerational transmission of indigenous knowledge and spirituality. The celebration was a living classroom, ensuring that the philosophy of Safuu (moral and ethical order) and the connection to the Oromo calendar, based on sophisticated astronomical observation, are not relegated to history books but remain a vibrant part of community life.

The event concluded with a communal meal, sharing of blessings, and a collective sense of renewal. As the sun set on the first day of 6420, the message from the Galma Amantaa at Walisoo Liiban was clear and resonant. It was a declaration that the Oromo spirit, guided by its ancient covenant with Waaqaa and nature, remains unbroken, steadfastly hoping for and working towards a year—and a future—defined by nagaa (peace), jaalala (love), and tokkummaa (unity).

Ilfinash Qannoo: A Symbol of Oromo Resilience

News Feature: The Unbroken Flame – Ilfinash Qannoo Embodies a Lifetime of Struggle and Steadfastness

GULLALLE, OROMIA – In the bustling activity of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) headquarters this Amajji 1 celebration, one figure sits with a quiet, palpable gravity. Ilfinash Qannoo, her body bearing the weight of years and the toll of relentless struggle, is a living archive of the Oromo quest for freedom. Too weak to stand, too ill to move independently, she is carried to gatherings, not as an invalid, but as a revered ember of the movement’s enduring fire.

Her presence is a testament, not to frailty, but to an indomitable will. It is the final, physical testament of a life offered completely—uleetti rarraatee—stretched across the altar of the Oromo struggle. Her commitment, born of a profound and unwavering love for the cause, saw her pour her energy into every space she could reach, for as long as she could manage, until her very body could no longer sustain the pace of the fight.

Today, on Oromo World Brotherhood Day (WBO), surrounded by a new generation of activists and leaders at the OLF Gullalle office, Ilfinash Qannoo’s role has transformed from frontline mobilizer to living monument and moral compass. Her journey is a bridge connecting the sacrifices of the past to the responsibilities of the present.

“A Seed That Moves Does Not Rot; The Dead Do Not Rise, So Do Not Fear Them.”

This powerful Oromo proverb, evoked by those who know her story, encapsulates her legacy. Ilfinash Qannoo was never static. She was a “seed” that moved—organizing, advocating, supporting—ensuring the ideas of liberation never stagnated or “rotted” in passivity. Her life’s work was to keep the movement in motion.

Now, her physical stillness speaks volumes. It forces a confrontation with the cost of the struggle and the solemn duty of those who remain. “Do not fear the dead,” the proverb advises, urging the living to act with the courage of those who can no longer stand. In her silent, observant presence, she embodies this charge, a silent reminder that the true threat is not the fallen, but the inaction of those who inherit their dreams.

Her life has been one of radical interdependence—naamaan deeggaramtee—leaning on and being leaned upon by the community she helped build. From providing shelter and intelligence in perilous times to offering counsel and moral support, her strength was always relational, woven into the fabric of the collective struggle.

As officials and well-wishers approach her chair on this day of celebration, they do not offer pity. They offer kabaja—deep respect. They bend to whisper words of gratitude, to seek a silent blessing from her weary eyes. The whispers that surround her are not about illness, but about endurance; not about an ending, but about a transcendent persistence.

“Ulfaadhu, umurii dheeradhu jenna!” – “Be strong, may you have long life!” is the fervent wish expressed for her. It is a wish for the longevity of the spirit she represents: the spirit of self-sacrifice, unconditional love for the cause, and an resilience that refuses to be extinguished.

Ilfinash Qannoo, in her dignified fragility, is more than an individual. She is a symbol. She represents every parent who lost a child, every activist who endured prison, every anonymous supporter who carried the movement forward in shadows. On this Amajji 1, as the Oromo people worldwide celebrate their brotherhood and identity, the image of Ilfinash Qannoo, carried to the heart of the movement’s headquarters, serves as the most profound reminder: that the journey is long, the cost is high, and the flame, once lit by love, must be tended by every generation.

Her silent message echoes in the hall: The seed must keep moving. Do not let it rot. And do not fear—build the future with the courage her life has demanded.

Honoring the Guardians of the Struggle

Feature Commentary

“Galata Qabsaa’otaa…” – Honor the Warriors. These words resonate as a sacred debt of gratitude within the Oromo community, a recognition of those who risked everything when the price of freedom was ultimate sacrifice.

In the tumultuous years following the fall of the Derg regime, a period of profound uncertainty and danger descended upon Ethiopia. For many Oromo freedom fighters, the dawn of a new era brought not peace, but a brutal twilight. Stripped of legal protection, they became targets—some left to perish from untreated wounds by the roadside, others hunted and thrown into the shadows of prisons. It was a time of severe crisis, a test of collective conscience.

Amidst this pervasive fear in Finfinnee (Addis Ababa), a flicker of humanity refused to be extinguished. A handful of Oromo residents, themselves navigating a treacherous landscape, made a courageous choice. They became protectors, hiding wounded and wanted fighters in plain sight, providing not just shelter but life-saving medicine and care. Their homes became field hospitals; their quiet defiance, a shield against the state’s wrath.

Among these unsung heroes is Obbo Araggaa Qixxataa. Born and raised in Dirree Incinnii, Oromia, he had come to Finfinnee as a businessman, establishing his life for many years in the Birbirsa Goora area. But when history demanded more than commerce, he answered. His residence became a sanctuary, a critical node in a clandestine network of survival. The business acumen that guided his public life was redirected to the covert logistics of preservation—securing medicine, arranging safe passage, sustaining lives that the official order sought to erase. Today, residing in America, his legacy is not measured in capital but in the lives he helped safeguard. Galataa fi Kabaja Oromummaatu isaanif mala! Gratitude and respect for Oromummaa are his rightful due.

This act of remembrance is being formally honored. The organization Oromo Global has undertaken the vital mission of strengthening and recognizing these aging veterans of the struggle. By bestowing acknowledgments like the one upon Obbo Araggaa, they perform a critical act of historical preservation—ensuring that the quiet bravery of the past is not lost to the noise of the present.

The Bottom Line:

The story of Obbo Araggaa Qixxataa is a microcosm of a broader, often unrecorded history. It reminds us that liberation movements are not sustained by soldiers and speeches alone. They are nourished by the shopkeeper who shares his bread, the homeowner who opens her door, and the businessman who uses his resources to heal rather than just to profit. Honoring the warriors also means honoring their guardians.

As organizations like Oromo Global step forward to say “Galata haa argatan”—let them receive thanks—they are piecing together a fuller, more human tapestry of resistance. They affirm that in the economy of gratitude, the currency of courage spent in dark times never depreciates.

Karrayyu Community’s Sacred Ritual for Power Transition

Karrayyu Gadaa Council Prepares Historic “Buttaa Qaluun” Rite for Leadership Transition

TARREE KEEDII, OROMIA — In accordance with the sacred eight-year cycles of the Oromo Gadaa system, the Karrayyu community is undertaking profound preparations for the Buttaa Qaluu ceremony—a pivotal ritual that facilitates the peaceful and systematic transfer of power from one Gadaa grade to the next.

Central to this process is the revered Baallii Gadoomaa (the scepter of Gadaa). Per Oromo law, the scepter is transferred every eight years. For the Karrayyu, the incumbent Gadaa council, having held the scepter and led the people for its designated eight-year term, is now charged with preparing the successor grade to assume power.

“The current Gadaa grade, having taken the Baallii Gadoomaa and governed for eight years, must now create the space—the Goobaa or Irreessa—for the next Gadaa set to rise,” explained a senior cultural analyst familiar with the rites. “This act of ‘giving space’ is a core constitutional principle of Gadaa, ensuring balanced, rotational, and non-hereditary leadership.”

The elaborate Buttaa Qaluu ceremony, now being organized at the sacred site of Tarree Keedii, is the formal mechanism for this transition. The term Goobaa itself encompasses the acts of vacating, clearing the path, mentoring, and imparting wisdom to the incoming leaders.

“The Karrayyu use Gadaa’s peaceful and consensual transfer of power as a model for national governance,” the analyst added. “The Goobaa demonstrates how leadership can be relinquished gracefully to ensure continuity and stability.”

Current Council Prepares the Ground

All eyes are now on the Gadaa Michillee council, the current custodians of power. Their critical preparatory duty is to receive the final blessings (Eebbaa) from the Abbaa Bokkuu (the presiding father) at their designated ritual ground (Ardaa).

Following this, they will proceed to the assembly site at Tarree Leedii to take their positions and oversee the meticulous execution of the Goobaa rituals. Their role is to ensure every sacred protocol is followed to legitimize and empower the incoming grade.

This meticulous process underscores the Gadaa system’s enduring sophistication as a indigenous system of democracy, conflict resolution, and constitutional governance. The Buttaa Qaluun ceremony is not merely a cultural event but a living enactment of a social contract that has guided the Oromo people for centuries.

The upcoming rites are expected to draw elders, scholars, and community members from across the region to witness this foundational practice of Oromo democracy in action.

# # #

About the Gadaa System:

Gadaa is the traditional, holistic social system of the Oromo people that governs political, economic, social, and religious life. It is based on an eight-year cyclical timeline, with power rotating democratically among five generational grades. In 2016, UNESCO inscribed the Gadaa system on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Gadaa Michillee Clan of Karrayyu Commences Historic “Cidha Buttaa” Ceremony

Muddee 26, 2025 — The esteemed Gadaa council of the Michillee clan within the Karrayyu Oromo nation has officially inaugurated the grand Cidha Buttaa ritual at Tarree Leedii, marking the beginning of a profound 12-day cultural and spiritual observance. The ceremony, which began on the 26th of Muddee (December), is set to conclude with major rites on the 26th and 27th.

The Cidha Buttaa is a complex sequence of traditional rites performed in a strict, consecutive order over its duration. The opening days have seen powerful foundational ceremonies:

Day 1 (Muddee 26):

- The Gadaa council members formally took their designated seats (Tarree Leedii).

- The sacred fire at the Abbaa Bokkuu’s (leader’s) hut was ignited.

- Blessing rituals (Eebbaa) were performed.

- A ritual of communion and sharing of ceremonial drink (Qubsuma) was held.

- Camels (Geejjiba) were paraded in a display of honor and strength.

- At Tulluu Huffeenna, a Kataarii tree was erected and burned, with prayers for abundance (Korbeessa Huffeenaa).

- The Raabaa officials conducted rituals involving a ceremonial staff (Dhaddacha) and the planting of a ritual stake (Ardaaga).

Day 2 (Muddee 27):

- A mature bull (Dullacha) was sacrificed at the entrance of the leader’s hut.

- Vigil was kept over the sacred fire and the Ardaaga stake.

From the third to the fifth day (Muddee 28-30), the focus shifted to construction: building the main ritual lodge (Galma), installing the central ritual object (Daasa Keessummaa), and constructing enclosures for cattle and camels.

The period from the fifth to the ninth day (Muddee 30-Amajjii 3) involves spiritual and communal deliberations:

- Pilgrimages to sacred sites like Uman, hills, and valleys.

- Prayers for peace to Waaqa (the Creator).

- A series of assemblies to discuss the preservation and transmission of Gadaa laws, customs, and clan identities.

- Deliberations on environmental stewardship and land protection.

All these preparatory rituals will lead to the climactic ceremonies on the tenth day.

Day 10 (Amajjii 6):

- At dawn, the final preparations (Hiiddii) will be made.

- A special shelter (Bitimaa) will be erected behind the cattle enclosure.

- In the afternoon, the Abbaa Galmaa (ceremony head) will stand before the shelter to formally authorize the appointed ritual actors (Gumaachitoota).

The Cidha Buttaa will then enter its final, most sacred phase on the night of the 6th of January, continuing into the 7th of January.

This elaborate ceremony reaffirms the vitality of the Gadaa system, serving as a critical mechanism for cultural renewal, social cohesion, spiritual blessing, and the intergenerational transfer of authority and knowledge among the Karrayyu Oromo.

Bokkuu and Qaalluu: The Sacred Pillars of Oromo Democracy

OROMIA — At the heart of the Oromo Gadaa system, an indigenous democratic governance structure recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, lies a refined balance of power and spirituality, embodied in two sacred pillars: the Bokkuu and the Qaalluu.

This dual authority forms the cornerstone of a system that has guided Oromo social, political, and spiritual life for centuries. Among the Karrayyuu Oromo, custodians of deeply traditional Gadaa practices, the Holder of the Bokkuu (Abbaa Bokkuu) leads the active Raaba Gadaa council, symbolizing lawful political authority, unity, and temporal governance.

The authority of the Bokkuu is absolute in ceremonial life. No Gadaa ritual—from a temporary ceremonial visit (jila) to a full-scale relocation of the assembly—can commence without its sacred blessing. The scepter is not merely a symbol; it is the source of legitimacy for all communal undertakings.

While the Abbaa Bokkuu governs the political, economic, and social spheres, spiritual authority rests with the Qaalluu. This sacred office is responsible for blessings, prayers for rain and fertility, and invoking peace (nagaa) for the land and people. This clear separation and interdependence of spiritual (Qaalluu) and temporal (Bokkuu) powers ensure a holistic system of checks and balances, preventing the concentration of power and aligning leadership with moral and divine will.

The system also has a built-in mechanism for continuity. In the absence of the Abbaa Bokkuu, leadership is seamlessly entrusted to the Abbaa Sabbataa, who acts as deputy to ensure governance never falters.

Furthermore, Oromo tradition dictates that for any Gadaa ceremony to be valid and declared complete, three indispensable elements must be present: men, women, and cattle. This triad represents the foundational pillars of Oromo society—humanity in its complementary duality, and the cattle that symbolize sustenance, wealth, and the covenant between the people and their environment.

This intricate structure highlights the Gadaa system’s sophistication, where democracy is not a secular political exercise but a sacred covenant involving the entire community, the natural world, and the divine. As modern governance seeks sustainable and inclusive models, the ancient balance of the Bokkuu and Qaalluu offers a timeless lesson in integrated leadership.

Karrayyu Gadaa Announces Historic Ceremony: Call to Witness Buttaa Qaluu and Passing of the Goobaa Scepter

OROMIA, ETHIOPIA – In a profound continuation of a centuries-old tradition, the Karrayyu Gadaa system has officially entered the preparatory phase for one of its most sacred rites: the Buttaa Qaluu ceremony and the formal transfer of the Goobaa, the leadership scepter. This pivotal event, scheduled to take place one week from today, marks a critical juncture in the eight-year Gadaa cycle, where power is peacefully passed to the next generation.

The Gadaa system, a UNESCO-recognized indigenous democratic and socio-political institution of the Oromo people, operates on a strict eight-year rotational leadership schedule. For the Karrayyu, this process involves a meticulous two-year preparatory period. The current Gadaa assembly is now finalizing preparations to hand over the Goobaa to the incoming class, ensuring the unbroken chain of governance, law, and cultural continuity.

“Karrayyu Gadaa continues its journey. The existing Gadaa, after two years of preparatory work, has begun the process of transferring leadership to the next group by presenting the Goobaa,” stated the official announcement.

The upcoming week will culminate in the Cidha Buttaa Qaluu, a specific and elaborate ritual that formalizes this transfer. The ceremony is not merely administrative but a deeply spiritual and communal reaffirmation of identity, law, and social order.

In a move that underscores the communal and intergenerational nature of Gadaa, the Karrayyu elders have extended a formal and respectful invitation to members of the community to witness this historic passage.

“In this regard, an invitation has been extended to you to participate as part of this history, to be present as the historical Cidha Buttaa Qaluu and the passing of the Goobaa are conducted next week,” the announcement declared.

The Goobaa is far more than a symbolic object; it is the embodiment of authority, justice, and the collective will of the people under Gadaa law. Its transfer is a carefully orchestrated event that educates the incoming leaders and binds them to their responsibilities.

The call concludes with a powerful affirmation of cultural purpose: “Guides of generations, let us manifest our culture together!”

The ceremony is expected to draw participants and observers from across the community, serving as a living testament to the resilience of the Gadaa system and its enduring role in guiding the social, political, and spiritual life of the Karrayyu Oromo.