Ethiopia’s Strategic Crossroads: When Criticism Blurs the Line Between Government and Nation

By Maatii Sabaa

Feature News

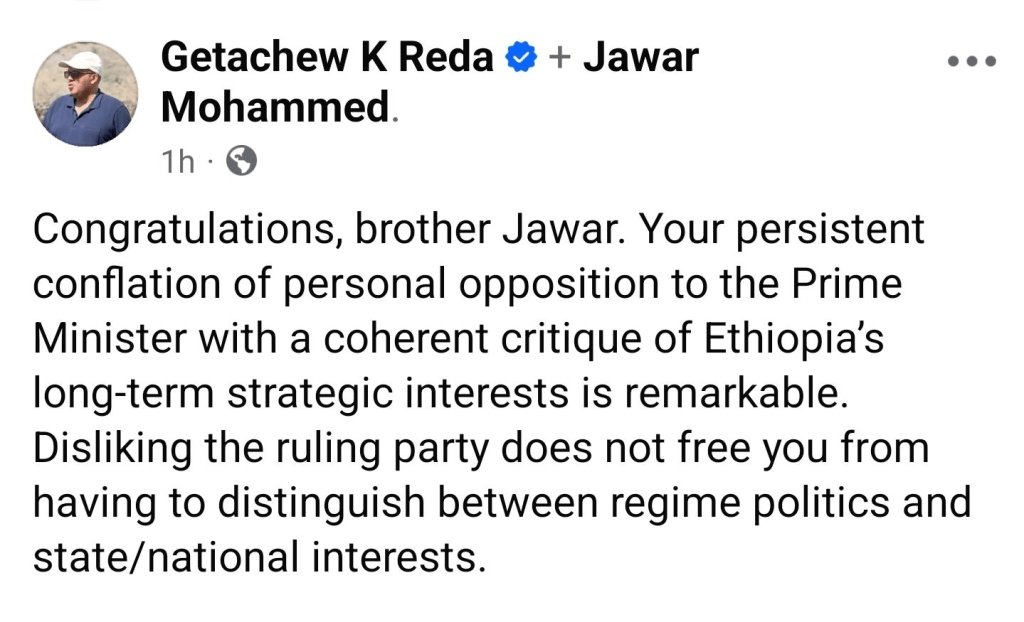

In the high-stakes arena of the Horn of Africa, where geopolitics shifts like tectonic plates beneath ancient soils, a troubling pattern has emerged in Ethiopia’s opposition discourse—one that increasingly conflates personal grievances against a sitting prime minister with the nation’s enduring strategic interests.

Over the past several days, Jawar Mohammed, once a close ally of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and now one of his most prominent critics, has launched a series of attacks against Ethiopia’s posture toward the deepening crisis in neighboring Sudan. His criticism, while occasionally resting on isolated facts, appears to systematically strip those facts of their broader strategic context—reducing complex national security calculations to evidence of government incompetence or malice.

The distinction being lost, critics argue, is one upon which stable democracies are built: the difference between the party in power and the state itself.

Facts Without Context: The Strategic Vacuum

Some of the reports circulated by Mohammed and his associates may be factually accurate in their narrowest sense. Ethiopia has indeed sought to protect its strategic interests amid Sudan’s collapse. It has engaged with actors on the ground. It has not adopted the posture of a passive observer.

Yet to present these moves as evidence of strategic folly—without reference to the regional power competition, Ethiopia’s existential stake in Sudanese stability, or the active interventions of other external actors—is to substitute selective outrage for sober analysis.

“The tragedy unfolding in Sudan is indeed exacerbated by foreign intervention,” one regional analyst noted, speaking on condition of anonymity. “But Ethiopia is hardly unique in pursuing its interests. What’s unique is Ethiopia’s vulnerability.”

No country in the region, and perhaps few beyond it, stands to lose more from a permanently destabilized Sudan. Ethiopia shares a 744-kilometer border with its northern neighbor. It hosts hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees. Its access to critical trade routes, its management of transboundary water resources, and its exposure to cross-border armed group proliferation are all directly implicated in Sudan’s trajectory.

Egypt and other regional actors are not neutral mediators. They have been actively shaping the conflict’s trajectory to favor preferred belligerents. To suggest that Ethiopia should operate as though this were not the case—or that acknowledging these realities somehow constitutes aggression—reflects what one foreign policy specialist described as “an aversion to the very language of national security.”

The Luxury of Abstraction

Mohammed positions himself as a politician-activist, a hybrid role that in theory could bridge grassroots mobilization and high-level policy engagement. But his recent posture suggests discomfort with the hard currency of statecraft: strategic interest, national security, geopolitical positioning.

In the Horn of Africa—a region defined by proxy competition, transboundary militant threats, and zero-sum maneuvering among rival states—such discomfort is not a virtue. It is a liability.

“States do not have the luxury of moral abstraction when core national interests are at stake,” said a former Ethiopian diplomat who requested anonymity to speak candidly. “You can critique how a government pursues those interests. You can propose alternative strategies. But to pretend that Ethiopia should have no strategy at all—or to frame every strategic move as evidence of malign intent simply because it originates from this prime minister—is not analysis. It’s partisan grievance dressed in policy language.”

The pattern has raised concerns among observers who note that Mohammed, widely believed to harbor ambitions for higher office, appears to be adopting what one analyst termed a “scorched-earth posture” not merely toward the Abiy administration but toward the Ethiopian state itself.

Governments Change. Geography Doesn’t.

This conflation carries implications beyond the immediate policy debates.

Governments are transient. Parties rise and fall. But strategic geography is stubborn. Ethiopia’s long-term national interests—its access to the sea, the security of its borders, the stability of its neighborhood, the viability of its water security arrangements—will outlast any single administration.

A credible political alternative, analysts argue, must demonstrate the capacity to distinguish between the party temporarily in power and the permanent interests of the nation. It must show that it can inherit the state without seeking to dismantle it.

“Thus far, Jawar has shown a near-pathological inability to make that distinction,” said Meheret Ayenew, a political scientist at Addis Ababa University. “The criticism never stops at the government. It bleeds into delegitimization of the state’s very right to defend its interests. That’s not opposition. That’s something else entirely.”

The Accountability Question

To be clear: critique of government policy is not only legitimate but essential. Ethiopia’s approach to the Sudan crisis, like any foreign policy posture, warrants scrutiny. Questions about coordination, consistency, and effectiveness are fair game.

But critique demands an alternative framework. What, precisely, should Ethiopia be doing differently? Should it abandon its engagement in Sudan entirely? Should it defer to Cairo’s preferred outcomes? Should it pretend that its national security is not implicated in the fate of its neighbor?

These questions, conspicuously absent from Mohammed’s recent broadsides, are the ones that distinguish serious opposition from performance.

Beyond the Immediate

The tragedy in Sudan has already claimed thousands of lives and displaced millions. For Ethiopia, the stakes are not abstract. They involve real security threats, real economic costs, and real humanitarian obligations that will persist regardless of who sits in the prime minister’s office in Addis Ababa.

In such moments, the distinction between government and state matters. A political culture that cannot sustain that distinction is one that struggles to produce durable alternatives—only perpetual opposition.

Whether Mohammed and his allies can evolve beyond this posture remains to be seen. But the clock is ticking. The region does not pause for Ethiopia to resolve its internal political debates.

And strategic interests, neglected or denied, have a way of asserting themselves regardless.

Challenges to PM Abiy Ahmed: Gedu’s Rebuttal on Tigray War

Senior Official Rebuts PM Abiy’s Claims, Alleges Cover-Up in Eritrean Role During Tigray War

[February 4, 2026] – In a scathing and meticulously detailed open letter to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Gedu Andargachew, a former high-ranking official, has issued a sharp rebuttal to the Prime Minister’s recent parliamentary statements, directly challenging the official narrative of Eritrea’s role in the Tigray war and accusing the administration of evading moral responsibility for the conflict’s atrocities.

The letter, dated January 27, 2015, Ethiopian Calendar, was prompted by the Prime Minister’s mention of Gedu by name during a parliamentary address concerning tensions with Eritrea on January 26, 2015, Ethiopian Calendar. Gedu states that this reference compelled him to “place the matter on the public record, without addition or subtraction,” offering a starkly different account of key wartime events.

Disputing the Official Eritrea Narrative

Gedu’s core contention challenges the timeline presented by the government. He asserts that Eritrean forces fought alongside the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) from the war’s outset until the Pretoria Agreement was finalized, contradicting the official line that their involvement was brief or contested.

He provides specific military details to support his claim, recalling a moment in the winter of 2013 E.C. (2020/2021 Gregorian) when Tigrayan forces advanced into the Amhara region. “We remember that the Eritrean army came as far as the Debretabor area and fought,” he writes. He further alleges that the ENDF and the Eritrean military conducted joint operations “in a manner resembling a single national army” until the peace deal was made public.

Alleging a Deliberate Cover-Up and Shift of Blame

The letter accuses PM Abiy of a pattern of deflecting responsibility for the war’s devastating human cost. Gedu expresses disappointment that instead of seeking forgiveness from the peoples of Tigray and Ethiopia, the Prime Minister chose to “simply provide explanations” and “try to find another party to blame.”

He argues this approach is not only a moral failure but also dangerous, stating it prevents the necessary lessons from being learned and “makes the recurrence of similar disasters possible.” Gedu directly links a range of national crises—the wars in Tigray and Oromia, alleged atrocities in Amhara, and conflicts in Benishangul-Gumuz—to what he calls the leadership’s “deficiency” and a flawed mindset that “cannot stay in power without conflict and war.”

Denying a Secret Mission to Eritrea

Gedu forcefully denies the Prime Minister’s insinuation that he was sent to Eritrea as a special envoy concerning the Tigray war. He clarifies he was removed from his post as Foreign Minister the day after the conflict began and states, “There has never been a suspicion that this issue was entrusted to me.”

He confirms a single trip to Asmara in early 2013 E.C. but describes a mission with entirely different objectives: to convey gratitude for Eritrea’s joint military cooperation, deliver a victory message regarding coordinated operations, and discuss mutual caution over mounting international “naming and shaming campaigns” related to human rights abuses.

Critically, Gedu claims that when he raised the international community’s demand for Eritrean troop withdrawal, PM Abiy explicitly instructed him not to request that Eritrea pull its forces out. “You warned me, ‘Do not at all ask them to withdraw your army,'” Gedu writes.

Revealing Contemptuous Remarks Toward Tigrayans

In the letter’s most explosive personal allegation, Gedu recounts a private meeting where he advised caution and the rapid establishment of civilian administration in Tigray to prevent future grievances. He claims PM Abiy dismissed these concerns with contemptuous rhetoric.

Gedu quotes the Prime Minister as allegedly stating: “Tigrayans will not rebel from now on; don’t think they can get up and fight seriously… we have crushed them so they cannot rise. Many people tell me ‘the people of Tigray, the people of Tigray’; how are the people of Tigray better than anyone? We have crushed them so they cannot rise. We will hit them even more; because the escape route is difficult, from now on the Tigray we know will not return.”

A Call for Accountability

The letter concludes not with personal grievances, but with a broader indictment of the administration’s governance. Gedu presents his detailed refutation as a necessary corrective to the historical record and an implicit call for a truthful accounting of the war’s origins, conduct, and consequences—an accounting he suggests is being actively avoided by the highest levels of government.

The Prime Minister’s office has not yet issued a public response to the allegations contained in the letter.

For more detail see the official Amharic letter of Gedu Andargachew

Asmerom Legesse: Champion of Oromo History and Gadaa System

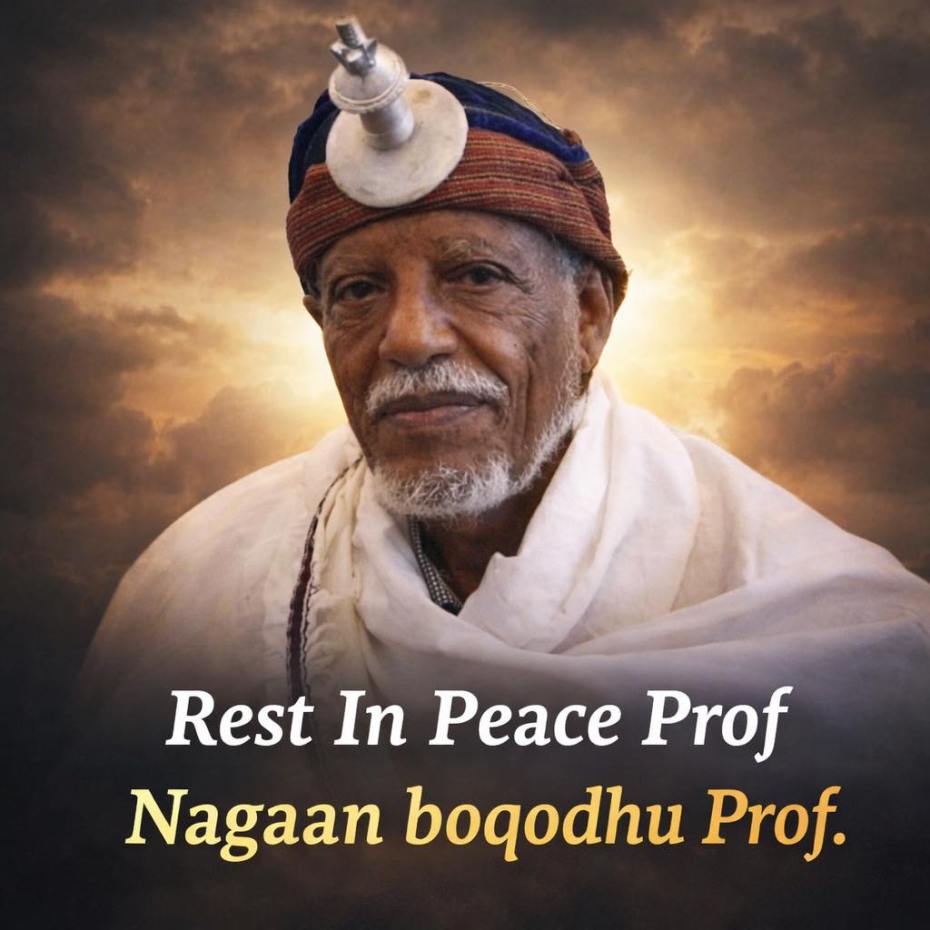

We are deeply saddened by the passing of Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse, a towering African intellectual whose scholarship stands among the most consequential contributions to Oromo history and African political thought.

Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse, an Eritrean social anthropologist trained at Harvard University and later a distinguished professor at institutions including Boston University, Northwestern University, Swarthmore College, and Yale University, devoted rare rigor and integrity to African knowledge systems. Yet his true stature was not defined by titles, but by the seriousness with which he treated the Oromo Gadaa system.

At a time when African societies were routinely dismissed as lacking political sophistication, he refused to reduce Gadaa to “custom” or folklore. Through disciplined research and cultural immersion, he framed Gadaa as an indigenous constitutional order—built on rotating generational leadership, codified law (seera), institutional checks and balances, accountability, and collective sovereignty.

His landmark work, Gadaa: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society (1973), introduced the world to the depth and coherence of Oromo political organization. Decades later, Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System (2000) further clarified Gadaa as an egalitarian democratic system whose institutional logic long predates modern Western models. These works remain core references for understanding Oromo governance and for challenging enduring stereotypes about African political thought.

Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse understood what many still refuse to acknowledge: Oromo history is not marginal, not invented, and not secondary to anyone else’s narrative. It is a complete intellectual tradition—deserving serious documentation, protection, and transmission. By recording Gadaa with scholarly precision, he did more than study Oromo society; he defended it against erasure and misrepresentation.

For this reason, Oromo communities came to hold him in special esteem, symbolically recognizing him as an “Abbaa Gadaa”—a guardian of truth and a custodian of a threatened heritage. Beyond Oromo studies, he wrote on Eritrean refugees, and wider questions of displacement, power, and justice in the Horn of Africa, embodying the responsibilities of a public intellectual.

We at OROMEDIA express our heartfelt condolences to his family, colleagues, students, and all communities touched by his life and work. We also offer our deep gratitude for the intellectual ground he helped secure for generations of Oromo scholars and citizens. His scholarship did not merely preserve the past; it equipped future generations with evidence and language to assert historical truth.

Rest in power, Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse. Your work lives on, wherever Gadaa is studied, defended, and lived as a testament to indigenous Oromo democracy and African intellectual greatness.

Professor Asmerom Legesse: A Champion of Oromo Democracy

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

A Guardian of Heritage: Advocacy for Oromia Mourns the Passing of Professor Asmerom Legesse (1931-2026)

(Melbourne, Victoria) – February 5, 2026 – Advocacy for Oromia, with profound respect and deep sorrow, announces the passing of the world-renowned scholar, Professor Asmerom Legesse. We extend our most heartfelt condolences to his family, his colleagues in academia, and to the entire Oromo people, for whom his work held monumental significance.

Professor Legesse was not simply an academic; he was a steadfast guardian and a preeminent global ambassador for the ancient Gadaa system, the sophisticated democratic and socio-political foundation of Oromo society. For more than forty years, he dedicated his intellect and passion to meticulously studying, documenting, and advocating for this profound indigenous system of governance, justice, and balanced social order.

His seminal work, including the definitive text Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System, transcended mere historical analysis. Professor Legesse’s scholarship performed a vital act of cultural reclamation and global education. It restored dignity to a marginalized history, affirmed the cultural identity of millions, and presented to the international community a powerful, self-originating model of African democracy that predated and paralleled Western constructs.

Born in Asmara in 1931, Professor Legesse’s intellectual journey—from political science at the University of Wisconsin to a doctorate in anthropology from Harvard University, where he later taught—was always directed by a profound sense of purpose. His research provided the rigorous, academic foundation for understanding indigenous African political philosophy.

His passing is felt as a deeply personal loss within our community, reminding us of the interconnected threads of Oromo history and resilience. On a recent visit to Asmara, a delegation from Advocacy for Oromia visited a site of immense historical importance: the church where Abbaa Gammachis and Aster Ganno, giants of faith and resistance, resided while translating the Bible into Afaan Oromo. It was there we learned that the family home of Professor Asmerom Legesse stood adjacent.

This physical proximity stands as a powerful metaphor. It connects the spiritual and linguistic preservation embodied by Abbaa Gammachis with the intellectual and political excavation led by Professor Legesse. They were neighbors not only in geography but in sacred purpose: both dedicated their lives to protecting, promoting, and elucidating the core pillars of Oromo identity against historical forces of erasure.

Professor Legesse’s lifetime of contributions has endowed current and future generations with the intellectual tools to claim their rightful place in global narratives of democracy and governance. For this invaluable and enduring gift, we offer our eternal gratitude.

While we mourn the silence of a towering intellect, we choose to celebrate the immortal legacy he leaves behind—a legacy of knowledge, pride, and empowerment that will continue to guide and inspire.

May his soul rest in eternal peace. May his groundbreaking work continue to illuminate the path toward understanding, justice, and self-determination.

Rest in Power, Professor Asmerom Legesse.

About Advocacy for Oromia:

Advocacy for Oromia is a global network dedicated to promoting awareness, justice, and the rights of the Oromo people. We work to uphold the principles of democracy, human rights, and cultural preservation central to Oromo identity and heritage.

Unpacking the Controversies in General Gonfa’s Narrative

Feature Commentary: Unpacking the Narrative – A Rebuttal to General Hailu Gonfa’s ETV Interview

By Daandii Ragabaa

February 1, 2026

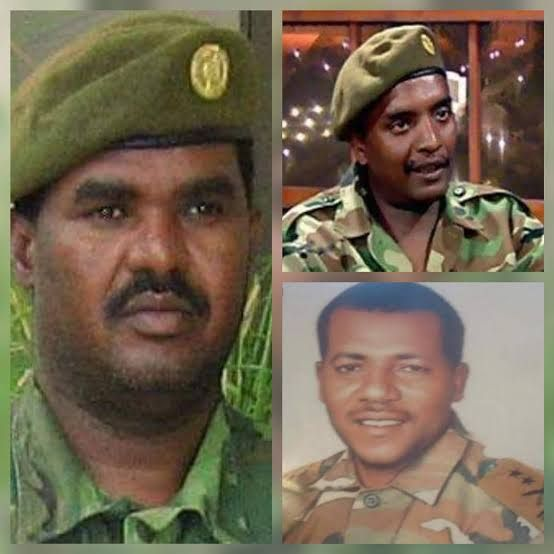

A recent interview given by General Hailu Gonfa, a former high-ranking member of the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), to Ethiopian state television (ETV) has sent ripples through political and activist circles. Presented as a “tell-all,” the interview was a stark narrative of disillusionment with the OLF/OLA, peppered with allegations of foreign manipulation and internal failure. For the state broadcaster, it was a coup—a former insurgent commander validating state narratives. For many observers, however, it was a performance laden with contradictions and historical revisionism that demands scrutiny, not passive acceptance.

General Gonfa’s core thesis is one of victimhood at the hands of the Eritrean government (Shaebia) and strategic confusion within the OLF/OLA. He paints a picture of being used, misled, and ultimately betrayed. Yet, a closer examination of his own points reveals a narrative more complex and less absolving of his own agency.

1. The Eritrea Conundrum: Pawns or Strategic Partners?

Gonfa claims they went to Eritrea not out of hatred for Ethiopia, but to oppose the system, following the path of Eritreans themselves. He then details a three-month military training at Camp Ashfaray, a period of intense hardship. The critical question he sidesteps is: what did he and his comrades believe they were building towards in Asmara? Did they receive a political program from the OLF leadership? As senior military cadres, did they simply execute orders without understanding the overarching political strategy? His portrayal reduces seasoned officers to naive children, which insults both their intelligence and the gravity of their decision to seek foreign military training.

2. The Phantom “Russian Assignment” and Internal Discord.

He recounts a meeting in Russia where OLF members approached him, but they could not agree on a common agenda for working inside Ethiopia. He claims he was later given a vague, “impossible” national assignment. This raises a fundamental question: if there was such profound disagreement on core strategy before undertaking major actions, why proceed? The attempt to blame subsequent failures on a pre-existing lack of consensus suggests a failure of leadership and collective decision-making, not merely the deceit of others.

3. The “Oromia Republic” Straw Man.

This is perhaps the most disingenuous claim. Gonfa asserts a foundational disagreement over the goal of an “Oromia Republic,” which he labels a “colonial agenda.” He claims this deadlock was irreconcilable. Yet, the public record shows that figures like General Kamal Galchu, in a VOA interview, spoke openly about the possibility of a republic after achieving liberation. Furthermore, the OLF’s own political programs have historically navigated the spectrum between self-determination and possible independence based on a popular referendum. To frame a central, debated political aspiration as a shocking, divisive “colonial” plot is a gross misrepresentation of the struggle’s own intellectual history, likely tailored for his current audience in Addis Ababa.

4, 5 & 7: The Shaebia Scapegoat and the Mystery of Betrayal.

Gonfa dedicates significant time to blaming Eritrea for their imprisonment and manipulating the OLA’s military wing. He describes a mysterious Colonel “Xamee” who allegedly controlled them. This narrative of total Eritrean control sits awkwardly with his other claims of internal OLA agency, such as the alleged refusal of some army units to follow orders in 2018. If the OLA was merely a puppet, how did it exercise such defiance? His testimony about Colonel Abebe (allegedly now a Brigadier General in the OLA) is particularly damaging but presented without context or corroboration. It creates a convenient fog where all failures can be attributed to a shadowy foreign hand, absolving internal leadership of critical misjudgments.

6. The Uncomfortable Transition from Refugee to Parliamentarian.

Gonfa’s personal journey—from an economic refugee with a Swedish passport to a member of parliament—is presented as a triumph of resilience. Yet, it unavoidably invites questions about the pathway from armed opposition to state legitimization. He speaks of the hardships of struggle, but for many watching, the stark contrast between the described suffering and his current official position underscores the complex, often ambiguous, transitions in Ethiopian political life, where former enemies can become state stakeholders.

8 & 9: Rewriting the Homecoming and the Gadaa Model.

He claims that upon returning to Ethiopia, they chose to work on national issues within the political system, respecting the existing OLF leadership. This sanitizes what many saw as a major split and a demobilization. His praise for the “Gadaa model” of conflict resolution, now being adopted in Amhara region, rings hollow. It appears less as a genuine endorsement of traditional systems and more as an endorsement of the federal government’s current policy of co-opting ethnic administrative models, a far cry from the Gadaa system’s principles of sovereignty and self-rule.

Conclusion: A Performance with a Purpose

General Hailu Gonfa’s interview is less a revelation and more a strategic repositioning. It is an effort to construct a personal and political narrative that reconciles a past of armed rebellion with a present of state accommodation. In doing so, it simplifies a multifaceted struggle into a story of foreign deception and internal error, draining it of its political substance and reducing it to a series of personal grievances and bad partnerships.

For the state, it is a useful narrative: the rebels were confused, controlled by Eritrea, and have now seen the light. For the still-active struggle, it is a warning about the power of state platforms to reshape history. For critical observers, it is a reminder that every testimony, especially those given in such loaded circumstances, must be read not just for what is said, but for the silences it cultivates and the interests it serves. The truth of the Oromo struggle, in all its sacrifice, complexity, and ongoing evolution, lies not in this single curated confession, but in the totality of its lived history, which is far messier, more principled, and more enduring than this interview suggests.

US-Ethiopia Accord: Unpacking the Anti-Terror Strategy

A Strategic Embrace: Reading Between the Lines of the US-Ethiopia “Anti-Terror” Accord

By Maatii Sabaa

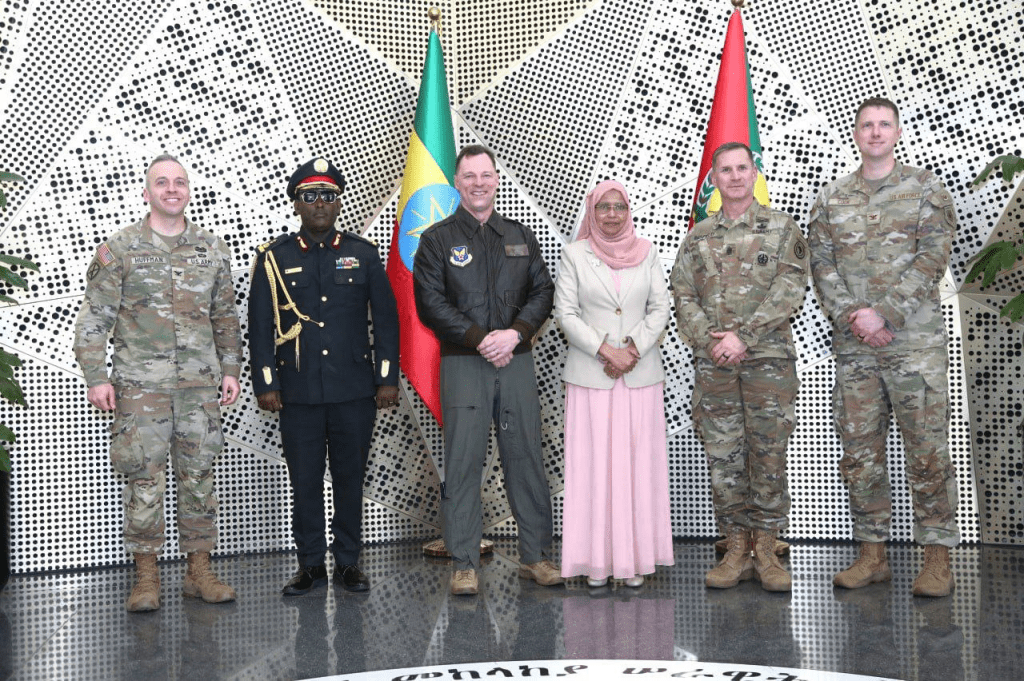

This week, the corridors of power in Addis Ababa hosted a meeting that was, on the surface, all about forward momentum. Ethiopian Defense Minister Engineer Aisha Mohammed received United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM) Commander General Dagvin Anderson, and the subsequent joint statement was a masterclass in diplomatic phraseology. The two nations, we are told, agreed to elevate their “growing diplomatic and military relations into a higher strategic partnership,” reaffirmed a shared commitment to “peace and security,” and—most pointedly—pledged to “jointly combat terrorism to safeguard their respective national interests.”

The language is smooth, strategic, and designed for international news wires. Yet, in the complex geopolitical theater of the Horn of Africa, such declarations are never just ink on paper. They are seismic signals, revealing shifting tectonic plates of influence, ambition, and realpolitik. To understand this meeting, one must read not just the statement, but the subtext, the timing, and the unspoken needs of both parties.

For the United States, represented by the commander of its African military umbrella, the engagement is a calibrated re-engagement. Ethiopia, long a cornerstone of US strategy in the region, experienced a profound rupture in relations following the Tigray War. The meeting signals a deliberate American pivot: from a posture of pressure and sanctions to one of renewed partnership, albeit with a clear, security-first agenda. The framing of “combating terrorism” provides a mutually acceptable chassis for this rebuilt relationship. It allows the US to re-establish critical military-to-military ties, secure influence in a strategically vital nation bordering volatile regions, and counter the deepening foothold of rivals like Russia and China. General Anderson’s presence at the 90th anniversary of the Ethiopian Air Force was not merely ceremonial; it was a symbolic reinvestment in a key institutional partner.

For the Ethiopian government of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the benefits are equally compelling, but stem from a position of seeking consolidation. Emerging from a devastating internal conflict and facing persistent security challenges—from insurgent groups in Oromia to tensions with neighboring Somalia—Addis Ababa craves international legitimacy and material support. A publicized strategic partnership with the world’s preeminent military power serves both ends. It burnishes the government’s diplomatic standing, frames its internal conflicts through the lens of a global “war on terror,” and potentially unlocks access to security assistance, intelligence sharing, and diplomatic cover. The phrase “safeguard their respective national interests” is crucial here; it acknowledges Ethiopia’s sovereign prerogative to define its threats, while America gains a partner in regional stability.

However, the term “terrorism” in this context is a Pandora’s Box. Who defines it? Which groups fall under this banner? The agreement risks providing international sanction for the domestic suppression of political dissent or armed resistance movements, branding them as terrorists in the name of shared security. This has profound implications for human rights and political negotiation within Ethiopia. Critics will argue that such pacts can embolden securitized approaches to complex political problems, prioritizing military solutions over dialogue and reconciliation.

Ultimately, the Addis Ababa meeting is a transaction. The United States gains a relaunched strategic foothold. Ethiopia gains validation and support. The glue binding the deal is a shared, if vaguely defined, enemy: “terrorism.” While the language speaks of peace and partnership, the underlying calculus is one of hard-nosed interest. The test of this new chapter will not be in the warmth of high-level meetings, but in the concrete actions that follow. Will it lead to greater stability and rights-respecting security in Ethiopia, or will it simply militarize a troubled landscape under a new banner of cooperation? The joint statement opens a door; what walks through it will define the true meaning of this strategic embrace.

The Truth Behind the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

Feature Commentary: Untangling the Nile – Correcting the Record on Africa’s Renaissance Dam

In the global discourse surrounding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), facts have often been submerged under waves of political rhetoric and historical bias. A recent intervention by former U.S. President Donald Trump, laden with sweeping inaccuracies, serves as a stark case study in how misinformation can poison complex transboundary issues. By examining his ten central claims, we can separate hydroelectric reality from hydrological fiction and recenter a conversation that is fundamentally about development, sovereignty, and dignity.

The False Financial Ledger

The assertion that “The United States paid for the dam” (Claim No. 1) is not merely incorrect; it is an erasure of a national endeavor. GERD stands as a monument to domestic sacrifice, funded by Ethiopian bonds, civil servant contributions, and public mobilization. This narrative of external funding subtly strips Ethiopia of its agency, reframing a sovereign project as a foreign-sponsored venture. The truth is more powerful: Africa’s largest hydropower plant is being built by Africans, for Africans.

The Hydro-Logic of Power, Not Theft

The core technical misrepresentations reveal a fundamental misunderstanding—or deliberate mischaracterization—of how a dam functions. GERD does not “stop the Nile” (Claim No. 2) nor did Ethiopia ever “cut off Egypt’s water” (Claim No. 3). A run-of-the-river hydropower plant generates electricity from the flow of water, which then continues downstream. It is not a reservoir of contention but a conduit of energy. Repeating the fiction of water theft does not make it fact; it manufactures a crisis where none exists.

The Colonial Claim vs. The Geographic Truth

The most historically loaded falsehood is that “The Nile belongs to Egypt” (Claim No. 4). This claim is a relic of colonial-era agreements from which Ethiopia was excluded. Over 86% of the Nile’s water originates in the Ethiopian highlands. A nation does not seek permission to use a river that springs from its own soil. Sovereignty over natural resources is not granted by historical habit or downstream hegemony.

Sovereignty, Not Permission

This leads directly to the paternalistic fantasy that “someone allowed Ethiopia to build this dam” (Claim No. 6). Ethiopia, a sovereign state, did not request nor require an external permit to develop its infrastructure. To frame GERD’s existence as something that was “allowed” is to deny the very essence of self-determination. Similarly, labeling national development as a “crisis Ethiopia created” (Claim No. 5) inverts the moral framework. The crisis is the persistent expectation that African nations should forgo electrification and growth to preserve an untenable status quo.

Weaponizing Rhetoric vs. Generating Watts

The rhetorical escalation to call GERD “a weapon” (Claim No. 7) or a direct threat to “Egypt’s survival” (Claim No. 8) is dangerous alarmism. The dam is concrete and steel, producing megawatts, not conflict. Egypt’s water security challenges—rooted in population growth and resource management—predate GERD. Blaming an upstream dam is a political diversion from difficult domestic reforms.

The Fallacy of the Outsider Savior & The Apology That Is Not Owed

Finally, the twin falsehoods of a solitary “powerful outsider” capable of solving the dispute (Claim No. 9) and that “Ethiopia must apologize for progress” (Claim No. 10) are two sides of the same coin. They suggest African agency is insufficient and that development is an offense. Sustainable resolution will come from good-faith negotiation among the Nile Basin nations—Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia—not from external diktat. And using one’s own resources to lift millions from energy poverty warrants celebration, not contrition.

The Real Dam Blocking Progress

In the end, GERD is not the problem. Ethiopia’s pursuit of development is not the problem. The problem, as this list of false claims makes abundantly clear, is misinformation. It is the circulation of outdated narratives, the weaponization of technical ignorance, and the refusal to acknowledge a simple truth: that the long-overdue renaissance the dam’s name promises is for Ethiopia, and its light need not dim any other nation’s future. The path forward is lit by facts, not fiction.

Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa: A Scholar’s Struggle in Oromia

A Scholar in Exile: The Plight of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa and a Community’s Anguish

A quiet crisis is unfolding in the heart of Oromia, one that speaks volumes about the precarious state of its intellectuals. Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa, a revered Oromo scholar, author, and elder, is reportedly in a dire situation, having lost his home and been forced to return to his birthplace in Qeellem Wallagga under difficult circumstances.

The news of Dr. Gammachuu’s troubles first circulated months ago but, as sources lament, “became a topic of discussion and then, while the Oromo community failed to find a solution, it was forgotten and left behind.” The issue was recently brought back to public attention through a poignant interview on Mo’aa Media, where the scholar himself confirmed the severity of his plight.

In the interview, Dr. Gammachuu shared a stark reality. After losing his house—reportedly sold to fund the publication of his scholarly work on Oromo history—he has returned to his ancestral land. “We have returned to our birthplace and are living there, farming our family’s land,” he stated, describing this turn as a significant hardship in his life. He revealed a history of being targeted, mentioning a prior expulsion from Addis Ababa University under the Derg regime.

His current predicament stems from a sacrifice for knowledge: “They sold their house to publish a book about the Oromo people,” he explained of the decision. He expressed frustration that people who know him seem unwilling to acknowledge his struggle, stating, “For the first time, I don’t know how this problem caught up with me, but I also don’t know how to be humiliated by a problem.”

The revelation has sparked profound concern and indignation within the Oromo community, both in Ethiopia and across the diaspora. The case of such an esteemed figure—a PhD holder who has contributed greatly to the preservation of Oromo history and culture—living without a stable home has become a powerful and troubling symbol.

The public reaction is crystallizing around urgent, critical questions directed at the Oromia Regional State government:

- Where is Oromo Wealth? Community members are asking, “The wealthy Oromos, where are they?” The question highlights a perceived disconnect between the region’s economic elite and the welfare of its most valuable intellectual assets.

- What is the Government’s Role? A more direct challenge is posed to the regional leadership: “The government that calls itself the government of the Oromo people spends money on festivals and various things. How is it that Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa, who has served the country with great distinction, has fallen through the cracks and is not provided a house?”

The situation of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa is no longer seen as a personal misfortune but as a test case. It tests the community’s commitment to honoring its elders and scholars, and it tests the regional government’s stated mission to uplift and protect the Oromo nation. His empty study is a silent indictment, and his return to the soil he has spent a lifetime documenting is a powerful, somber metaphor. The Oromo public now watches and waits to see if a solution will be found for one of its own, or if his struggle will remain an unanswered question in the ongoing narrative of Oromo self-determination.

Unfinished Liberation: The Oromo People at a Crossroads of Struggle and Resurgence

A PRESENT OF PROTEST, A FUTURE OF POSSIBILITY**

The story of the Oromo people, the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, has long been narrated as a history of resistance against centuries of marginalization. But history is not a closed book. As the community moves through the 21st century, its narrative is one of a profound and tense present—a reality where deep-rooted political challenges coexist with an unprecedented cultural revival, and where the struggle for self-determination is being redefined by a new generation.

This sixth chapter of Oromo history is not about the past; it is a living document, written daily in protests, in songs, in displacement camps, and in the global halls of advocacy.

The Persistent Political Paradox

Demography has not translated into democracy for the Oromo. Constituting an estimated 35-40% of Ethiopia’s population, they remain in a paradoxical position: a numerical majority without commensurate political power. Critical decisions concerning land, security, and resources are still centralized, leaving many Oromos feeling politically sidelined in their own homeland. This structural marginalization is the bedrock of ongoing discontent and the primary catalyst for the powerful protest movements that have shaken the nation over the past decade.

A Landscape of Insecurity and Displacement

The political tension has a human cost. In recent years, several Oromia regions have been plagued by instability. Reports from human rights organizations and media detail cycles of violence involving armed groups and state security forces, leading to civilian casualties, widespread internal displacement, and persistent allegations of rights abuses. Families have been uprooted, farms abandoned, and a pervasive climate of fear has disrupted the social fabric, casting a long shadow over daily life and economic stability.

The Unbreakable Spirit: Cultural Renaissance

Against this challenging backdrop, a powerful counter-narrative flourishes: a cultural renaissance. The Oromo language, *Afaan Oromo*, once suppressed, is now a working language of the Oromia region and is thriving in media, education, and digital spaces. Oromo music, art, and literature are experiencing a golden age, with artists like the late Hachalu Hundessa becoming national icons of resistance and identity. This cultural reawakening is not a retreat but a reclamation—a tool of resilience and a defiant affirmation of existence. Young people, in particular, wear their Oromo identity with a pride that is both personal and political.

The New Architects: Qeerroo and Qarree

The engines of this new chapter are the youth (*Qeerroo*) and women (*Qarree*). The *Qeerroo* movement, a leaderless network of young Oromos, demonstrated its formidable power in the 2014-2018 protests that helped usher in a political transition. Simultaneously, *Qarree*—Oromo women—are moving powerfully from the background to the forefront, organizing, advocating, and demanding a seat at every table, challenging both external oppression and internal patriarchy. Their grassroots activism represents the most dynamic force in contemporary Oromo society.

A Global Struggle with a Peaceful Heart

Oromo activism has consistently emphasized peaceful resistance, even in the face of violence. This principled stance, coupled with the strategic work of a large and mobilized global diaspora, has successfully internationalized the Oromo question. From parliaments in Washington and Brussels to universities worldwide, the call for Oromo rights and self-determination is now part of the global discourse on human rights and federalism in Ethiopia.

Hope Anchored in Unity and Knowledge

The path forward is fraught but illuminated by a clear vision. Community leaders and intellectuals stress that the future hinges on internal unity, a deep understanding of their own history, and an unwavering commitment to peaceful struggle and dialogue. The goal is not just political change but the building of a society where Oromo identity is the foundation for dignity, justice, and shared prosperity.

Conclusion: A Story Still Being Told

This Oromo history confirms that their story is still unfolding. It is a present-tense narrative of simultaneous pain and power, of loss and limitless cultural vitality. The struggle for a truly equitable place within Ethiopia continues, but it is now carried by a generation armed with history, mobilized by technology, and inspired by an unbroken spirit. The Oromo history, as it is written today, remains—above all—a enduring story of survival, resistance, and an undimmed hope for a future of their own making.

Oromo Diaspora Celebrates 46th OLA Anniversary Online

Oromo Diaspora Marks 46th OLA Anniversary and New Year with Virtual Gathering, Honors Foundational Victory

January 2, 2026-In a significant online assembly bridging continents, the global Oromo community gathered on January 2, 2026, for a dual commemoration: the 46th anniversary of the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA/WBO) and the celebration of Ayyaana Amajjii 1, the Oromo New Year. The virtual event, held via Zoom, served as a space for reflection, strategic review, and a powerful reaffirmation of commitment to the liberation struggle.

The gathering provided a platform to assess the achievements and persistent challenges of the Oromo quest for self-determination. Speakers connected the modern struggle directly to its historical roots, with participant Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo detailing the harsh founding conditions of the OLA. He highlighted a pivotal foundational moment: the first official day of the OLA was celebrated on January 1, 1980, to mark a victory over a major campaign by the then-ruling Darg (Derg) regime. This historical note underscored that the movement was born not in abstraction, but in the crucible of direct combat and early triumph.

The intertwining of the cultural New Year (Ayyaana Amajjii) with the military anniversary was emphasized as a core feature of Oromo resistance, symbolizing the inseparable link between cultural identity and political struggle. Organizers stated that these dates are perennially observed wherever Oromo patriots, members of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF/ABO), and supporters of the cause are found.

A central and poignant message was directed at the Oromo youth. In his keynote address, Dr. Daggafaa Abdiisaa framed the continuation of the struggle as a sacred duty inherited from past sacrifices, declaring, “The duty to pursue the goal and objective of the OLF rests upon you, the beloved children of the fallen heroes.”

The event concluded with a sense of solemn purpose, honoring the legacy of the last 46 years—from the first victory commemorated in March 1980 to the present-day resistance—while charting a determined course for the future. It reinforced the global diaspora’s role as a pillar of solidarity and historical memory for the ongoing movement in Oromia.

###

Background Notes:

- The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA/WBO) is the armed wing associated with the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF/ABO).

- On January 1, 1980, the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) celebrated its first formal day to commemorate a hard-fought victory over the Darg regime’s campaigns.

- This day stands as a testament to the early courage and sacrifice that laid the foundation for the ongoing struggle. We remember, honor, and draw strength from the resilience shown from the very beginning.

- Ayyaana Amajjii 1 marks the Oromo New Year based on the traditional Gadaa calendar.

- The OLA’s first commemorative day was March 1, 1980, following a military victory against the Derg (Darg) government.

- The Oromo have been engaged in a long-standing struggle for self-determination within Ethiopia.