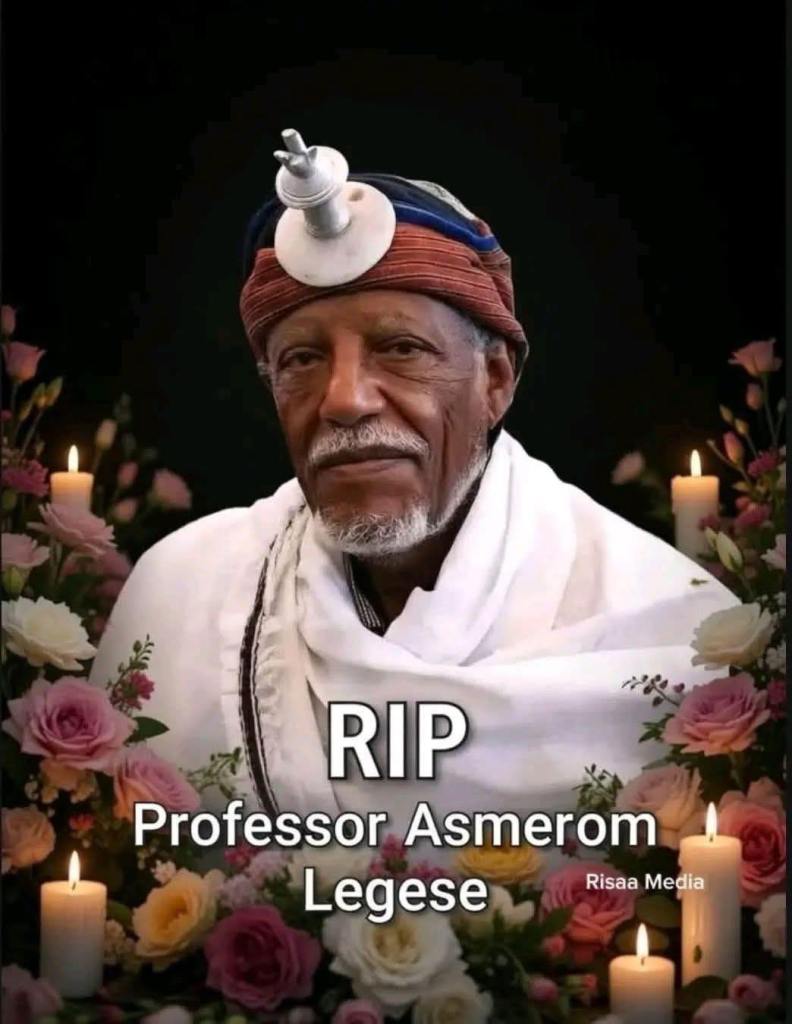

Borana University Mourns a Beacon of Indigenous Knowledge: Professor Asmarom Legesse

Borana University Mourns a Beacon of Indigenous Knowledge: Professor Asmarom Legesse

(Yabelo, Oromia – February 5, 2026) Borana University, an institution deeply embedded in the cultural landscape it studies, today announced its profound sorrow at the passing of Professor Asmarom Legesse, the preeminent anthropologist whose lifelong scholarship fundamentally defined and defended the indigenous democratic traditions of the Oromo people. The University’s tribute honors the scholar not only as an academic giant but as a “goota” (hero) for the Oromo people and for Africa.

In an official statement, the University highlighted Professor Legesse’s “lifelong dedication to understanding the complexities of Ethiopian society—especially the Gadaa system,” crediting him with leaving “an indelible mark on both the academic and cultural landscapes.” This acknowledgment carries special weight from an institution situated in the heart of the Borana community, whose traditions formed the bedrock of the professor’s most celebrated work.

The tribute detailed the pillars of his academic journey: a Harvard education, esteemed faculty positions at Boston University, Northwestern University, and Swarthmore College, and the groundbreaking field research that led to his seminal texts. His 1973 work, “Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society,” was cited as revolutionary for revealing “the innovative solutions indigenous societies developed to tackle the challenges of governance.”

It was his 2000 magnum opus, however, that solidified his legacy as the definitive voice on the subject. In “Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System,” Professor Legesse meticulously documented a system characterized by eight-year term limits for all leaders, a sophisticated separation of powers, and the Gumi assembly for public review—a structure that presented a centuries-old model of participatory democracy. “His insights challenged prevalent misconceptions about African governance,” the University noted, “showcasing the rich traditions and political innovations of the Oromo community.”

For his unparalleled contributions, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters from Addis Ababa University in 2018.

Perhaps the most powerful element of the University’s statement was its framing of his legacy beyond academia. By “intertwining the mechanics of the Gadaa system with the broader narrative of Oromo history and cosmology,” Professor Legesse was credited with fostering “a profound understanding of Oromo cultural identity.” It is for this work of preservation, interpretation, and transmission that he is declared “a hero—a goota—to the Oromo people and to Africa as a whole.”

Looking forward, Borana University management has called upon its students and faculty to honor his memory through “ongoing research and discourse on indigenous governance systems,” ensuring his foundational work continues to inspire new generations of scholars.

The entire university community extended its deepest condolences to Professor Legesse’s family, friends, and loved ones, mourning the loss of a true champion of Oromo culture and a guiding light in the study of African democracy.

About Borana University:

Located in Yabelo, Borana Zone, Oromia, Borana University is a public university committed to academic excellence, research, and community service, with a focus on promoting and preserving the rich cultural and environmental heritage of the region and beyond.

Remembering Prof. Asmerom Legesse: A Legacy of Oromo Scholarship

By Daandii Ragabaa

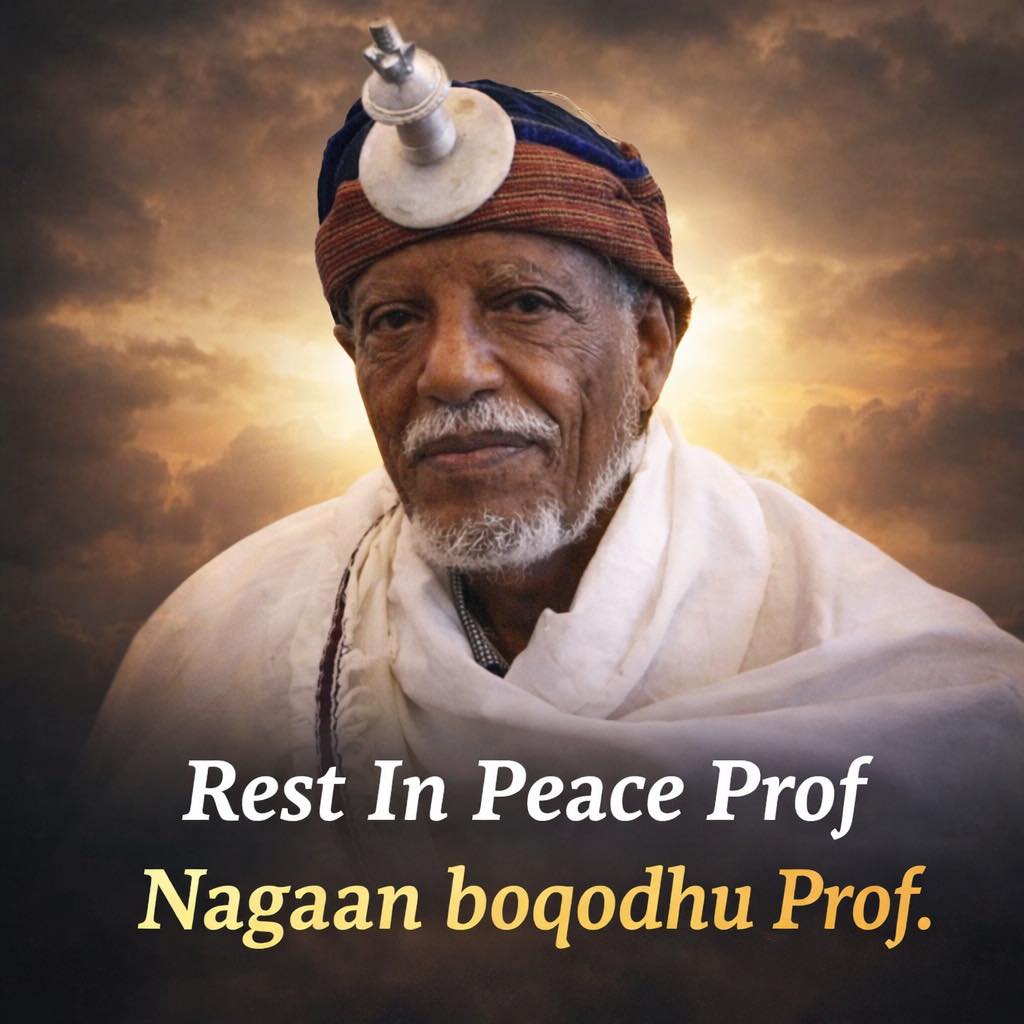

A Scholar Immortal: Prof. Asmerom Legesse’s Legacy Lives in the Hearts of a Nation

5 February 2026 – Across the globe, from the halls of academia to the living rooms of the diaspora, the Oromo community is united in a chorus of grief and profound gratitude. The passing of Professor Asmerom Legesse at the age of 94 is not merely the loss of a preeminent scholar; it is, as countless tributes attest, the departure of a cherished friend, a fearless intellectual warrior, and an adopted son whose life’s work became the definitive voice for Oromo history and democratic heritage.

The outpouring of personal reflections paints a vivid portrait of a man whose impact was both global and deeply intimate. Olaansaa Waaqumaa recalls a brief conversation seven years ago, where the professor’s conviction was unwavering. “Yes! It is absolutely possible,” he declared when asked if the Gadaa system could serve as a modern administrative framework. “The scholars and new generation must take this mantle, think critically about it, and bridge it with modern governance,” he advised, passing the torch to future generations.

This personal mentorship extended through his work. Scholar Luba Cheru notes how Professor Legesse’s 1973 seminal text, Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society, became an indispensable guide for her own decade-long research on the Irreecha festival. She reflects, “I never met him in person, but his work filled my mind.”

Ituu T. Soorii frames his legacy as an act of courageous resistance against historical erasure. “When the Ethiopian empire tried to erase Oromo existence, Professor Asmarom rose with courage to proclaim the undeniable truth,” they write, adding a poignant vision: “One day, in a free Oromiyaa, his statues will rise—not out of charity, but out of eternal gratitude.” Similarly, Habtamu Tesfaye Gemechu had earlier praised him as the scholar who shattered the conspiracy to obscure Oromo history, “revealing the naked truth of the Oromo to the world.”

Echoing this sentiment, Dejene Bikila calls him a “monumental figure” who served as a “bridge connecting the ancient wisdom of the Oromo people to the modern world.” This notion of the professor as a bridge is powerfully affirmed by Yadesa Bojia, who poses a defining question: “Did you ever meet an anthropologist… whose integrity was so deeply shaped by the culture and heritage he studied that the people he wrote about came to see him as one of their own? That is the story of Professor Asmerom Legesse.”

Formal institutions have also affirmed his unparalleled role. The Oromo Studies Association (OSA), which hosted him as a keynote speaker, stated his work “fundamentally reshaped the global understanding of African democracy.” Advocacy for Oromia and The Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau hailed him as a “steadfast guardian” of Oromo culture, whose research was vital for UNESCO’s 2016 inscription of the Gadaa system as Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Binimos Shemalis reiterates that his “groundbreaking and foundational work… moved [Oromo studies] beyond colonial-era misrepresentations.” Scholar Tokuma Chala Sarbesa details how his book Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System proved the Gadaa system was a sophisticated framework of law, power, and public participation, providing a “strong foundation for the Oromo people’s struggle for identity, freedom, and democracy.”

The most recent and significant political tribute came from Shimelis Abdisa, President of the Oromia Regional State, who stated, “The loss of a scholar like Prof. Asmarom Legesse is a great damage to our people. His voice has been a lasting institution among our people.” He affirmed that the professor’s seminal work proved democratic governance originated within the Oromo people long before it was sought from elsewhere.

Amidst the grief, voices like Leencoo Miidhaqsaa Badhaadhaa offer a philosophical perspective, noting the professor lived a full 94 years and achieved greatness in life. “He died a good death,” they write, suggesting the community should honor him not just with sorrow, but by learning from and adopting his teachings.

As Seenaa G-D Jimjimo eloquently summarizes, “His scholarship leaves behind not just a legacy for one community, but a gift to humanity.” While the physical presence of this “real giant,” as Anwar Kelil calls him, is gone, the consensus is clear: the intellectual and moral bridge he built is unshakable. His legacy, as Barii Milkeessaa simply states, ensures that while “the world has lost a great scholar… the Oromo people have lost a great sibling.”

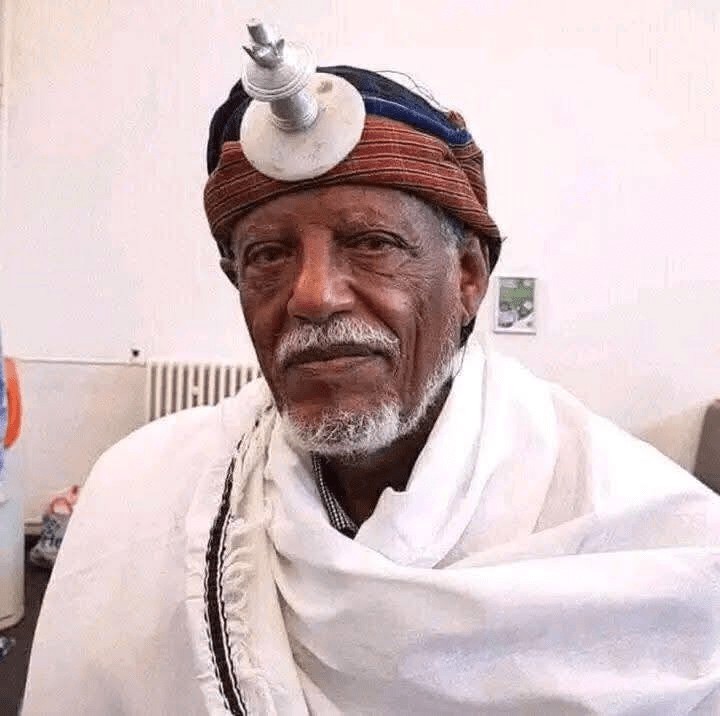

Asmerom Legesse: Champion of Oromo History and Gadaa System

We are deeply saddened by the passing of Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse, a towering African intellectual whose scholarship stands among the most consequential contributions to Oromo history and African political thought.

Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse, an Eritrean social anthropologist trained at Harvard University and later a distinguished professor at institutions including Boston University, Northwestern University, Swarthmore College, and Yale University, devoted rare rigor and integrity to African knowledge systems. Yet his true stature was not defined by titles, but by the seriousness with which he treated the Oromo Gadaa system.

At a time when African societies were routinely dismissed as lacking political sophistication, he refused to reduce Gadaa to “custom” or folklore. Through disciplined research and cultural immersion, he framed Gadaa as an indigenous constitutional order—built on rotating generational leadership, codified law (seera), institutional checks and balances, accountability, and collective sovereignty.

His landmark work, Gadaa: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society (1973), introduced the world to the depth and coherence of Oromo political organization. Decades later, Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System (2000) further clarified Gadaa as an egalitarian democratic system whose institutional logic long predates modern Western models. These works remain core references for understanding Oromo governance and for challenging enduring stereotypes about African political thought.

Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse understood what many still refuse to acknowledge: Oromo history is not marginal, not invented, and not secondary to anyone else’s narrative. It is a complete intellectual tradition—deserving serious documentation, protection, and transmission. By recording Gadaa with scholarly precision, he did more than study Oromo society; he defended it against erasure and misrepresentation.

For this reason, Oromo communities came to hold him in special esteem, symbolically recognizing him as an “Abbaa Gadaa”—a guardian of truth and a custodian of a threatened heritage. Beyond Oromo studies, he wrote on Eritrean refugees, and wider questions of displacement, power, and justice in the Horn of Africa, embodying the responsibilities of a public intellectual.

We at OROMEDIA express our heartfelt condolences to his family, colleagues, students, and all communities touched by his life and work. We also offer our deep gratitude for the intellectual ground he helped secure for generations of Oromo scholars and citizens. His scholarship did not merely preserve the past; it equipped future generations with evidence and language to assert historical truth.

Rest in power, Abbaa Gadaa Professor Asmerom Legesse. Your work lives on, wherever Gadaa is studied, defended, and lived as a testament to indigenous Oromo democracy and African intellectual greatness.

Oromo Community Mourns a Great Scholar: Asmerom Legesse’s Impact

Feature Commentary

A World Mourns an Intellectual Giant: Unified Tributes Honor Professor Asmerom Legesse, Scholar of Oromo Democracy

4 February 2026 – The global Oromo community, alongside academic and cultural institutions, is united in profound grief following the passing of Professor Asmerom Legesse, the preeminent scholar whose life’s work defined the study of the Oromo Gadaa system. Hailed as a “towering scholar,” “global voice,” and “steadfast guardian,” his death has prompted a powerful wave of tributes that collectively affirm his unparalleled role in bringing an indigenous African democratic tradition to the world stage.

Across statements from scholars, activists, and organizations, a consistent narrative emerges: Professor Legesse was far more than an academic. He was a truth-teller, a bridge-builder, and a revolutionary intellectual who dedicated his career to the reclamation and elevation of a system long marginalized by colonial and oppressive narratives.

Scholars and Leaders Reflect on a Transformative Legacy

Prominent voices have emphasized the transformative nature of his work. Scholar Asebe Regassa called him a “pioneer of Gadaa studies,” whose “groundbreaking anthropological work” ensured he will be “remembered forever.” Tayiba Hassen Kayo noted his “unwavering commitment” left an “enduring mark on academia and on the Oromoo people,” ensuring his life’s work “will never be forgotten.”

The personal dimension of his scholarship was highlighted by Israel Fayisa, who poignantly described him as “Eritrean by birth and Oromo by choice,” a scholar treated “like an enemy by many Ethiopianist scholars merely because he dedicated his life to revealing the truth.” This sentiment underscores the courageous stance his research represented.

A Legacy of Global Recognition and Cultural Pride

His work is credited with achieving what once seemed impossible: securing global academic respect for an indigenous African system. As Visit Oromia stated, his research “gave international recognition to one of Africa’s most remarkable indigenous governance systems.” Activist Dereje Hawas pointed out that what defined him was “the seriousness with which he treated African and especially Oromo knowledge systems,” elevating them to their rightful place in global discourse.

Activist and journalist Dhabessa Wakjira captured the core of his academic revolution, writing that Legesse “proved definitively that principles of equality, rotational leadership, checks and balances, and the rule of law were not foreign imports to the continent, but were deeply embedded, living traditions.” This work, as Lelise Dhugaa noted, was foundational to UNESCO’s inscription of the Gadaa system as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.

A Community’s Deep Personal Loss

For the Oromo people, the loss is both intellectual and deeply personal. The tribute from Olumaa Qubee expresses this communal grief: “Oromoon fira guddaa tokko dhabe” (“The Oromo people have lost a great sibling”). The call for schools and institutions to be named in his honor within Oromia reflects a desire to anchor his legacy physically in the land of the people he championed.

As tributes from colleagues like Zewdu Lechissa remember the “truly brilliant scholar and a kind soul,” the collective message is one of both mourning and determined continuity. Professor Asmerom Legesse’s pioneering scholarship did not merely document the Gadaa system; it restored a pillar of Oromo identity and gifted the world a timeless model of democracy. His legacy, as echoed by all, will undoubtedly “continue to inspire generations.”

Condolence Message from the Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau

The Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau expresses its profound sorrow and deep sense of loss at the passed away of Professor Asmarom Legesse, an eminent scholar, cultural custodian, and an unwavering servant of the Gada system.

Professor Asmarom devoted his life to the preservation, interpretation, and transmission of the Gadaa system—a living heritage of governance, justice, peace, and social responsibility. Through his scholarship, leadership, and lifelong service, he played an indispensable role in safeguarding the philosophical foundations and moral values that define Oromo identity and humanity at large.

His work bridged generations, linking ancestral wisdom with contemporary knowledge, and ensured that the Gadaa system remains a guiding light for social harmony, equity, and collective responsibility.

Beyond academia, Professor Asmarom stood as a moral compass for his community. He embodied the principles of truth, justice, service, and integrity, and tirelessly worked to nurture unity, dialogue, and cultural continuity. His contributions have left an enduring imprint on cultural institutions, academic circles, and community life, both within Oromiyaa and beyond.

On behalf of the Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau, we extend our heartfelt condolences to his family, relatives, colleagues, students, and the entire Oromo community who mourn this irreplaceable loss. While his physical presence has departed, his wisdom, teachings, and exemplary life will continue to live on, inspiring generations to uphold the values of Gada and to serve society with dedication and humility.

May the Almighty grant strength and solace to all who grieve his passing.

May his soul rest in eternal peace.![]()

Professor Asmerom Legesse: A Champion of Oromo Democracy

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

A Guardian of Heritage: Advocacy for Oromia Mourns the Passing of Professor Asmerom Legesse (1931-2026)

(Melbourne, Victoria) – February 5, 2026 – Advocacy for Oromia, with profound respect and deep sorrow, announces the passing of the world-renowned scholar, Professor Asmerom Legesse. We extend our most heartfelt condolences to his family, his colleagues in academia, and to the entire Oromo people, for whom his work held monumental significance.

Professor Legesse was not simply an academic; he was a steadfast guardian and a preeminent global ambassador for the ancient Gadaa system, the sophisticated democratic and socio-political foundation of Oromo society. For more than forty years, he dedicated his intellect and passion to meticulously studying, documenting, and advocating for this profound indigenous system of governance, justice, and balanced social order.

His seminal work, including the definitive text Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System, transcended mere historical analysis. Professor Legesse’s scholarship performed a vital act of cultural reclamation and global education. It restored dignity to a marginalized history, affirmed the cultural identity of millions, and presented to the international community a powerful, self-originating model of African democracy that predated and paralleled Western constructs.

Born in Asmara in 1931, Professor Legesse’s intellectual journey—from political science at the University of Wisconsin to a doctorate in anthropology from Harvard University, where he later taught—was always directed by a profound sense of purpose. His research provided the rigorous, academic foundation for understanding indigenous African political philosophy.

His passing is felt as a deeply personal loss within our community, reminding us of the interconnected threads of Oromo history and resilience. On a recent visit to Asmara, a delegation from Advocacy for Oromia visited a site of immense historical importance: the church where Abbaa Gammachis and Aster Ganno, giants of faith and resistance, resided while translating the Bible into Afaan Oromo. It was there we learned that the family home of Professor Asmerom Legesse stood adjacent.

This physical proximity stands as a powerful metaphor. It connects the spiritual and linguistic preservation embodied by Abbaa Gammachis with the intellectual and political excavation led by Professor Legesse. They were neighbors not only in geography but in sacred purpose: both dedicated their lives to protecting, promoting, and elucidating the core pillars of Oromo identity against historical forces of erasure.

Professor Legesse’s lifetime of contributions has endowed current and future generations with the intellectual tools to claim their rightful place in global narratives of democracy and governance. For this invaluable and enduring gift, we offer our eternal gratitude.

While we mourn the silence of a towering intellect, we choose to celebrate the immortal legacy he leaves behind—a legacy of knowledge, pride, and empowerment that will continue to guide and inspire.

May his soul rest in eternal peace. May his groundbreaking work continue to illuminate the path toward understanding, justice, and self-determination.

Rest in Power, Professor Asmerom Legesse.

About Advocacy for Oromia:

Advocacy for Oromia is a global network dedicated to promoting awareness, justice, and the rights of the Oromo people. We work to uphold the principles of democracy, human rights, and cultural preservation central to Oromo identity and heritage.

Unpacking the Controversies in General Gonfa’s Narrative

Feature Commentary: Unpacking the Narrative – A Rebuttal to General Hailu Gonfa’s ETV Interview

By Daandii Ragabaa

February 1, 2026

A recent interview given by General Hailu Gonfa, a former high-ranking member of the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), to Ethiopian state television (ETV) has sent ripples through political and activist circles. Presented as a “tell-all,” the interview was a stark narrative of disillusionment with the OLF/OLA, peppered with allegations of foreign manipulation and internal failure. For the state broadcaster, it was a coup—a former insurgent commander validating state narratives. For many observers, however, it was a performance laden with contradictions and historical revisionism that demands scrutiny, not passive acceptance.

General Gonfa’s core thesis is one of victimhood at the hands of the Eritrean government (Shaebia) and strategic confusion within the OLF/OLA. He paints a picture of being used, misled, and ultimately betrayed. Yet, a closer examination of his own points reveals a narrative more complex and less absolving of his own agency.

1. The Eritrea Conundrum: Pawns or Strategic Partners?

Gonfa claims they went to Eritrea not out of hatred for Ethiopia, but to oppose the system, following the path of Eritreans themselves. He then details a three-month military training at Camp Ashfaray, a period of intense hardship. The critical question he sidesteps is: what did he and his comrades believe they were building towards in Asmara? Did they receive a political program from the OLF leadership? As senior military cadres, did they simply execute orders without understanding the overarching political strategy? His portrayal reduces seasoned officers to naive children, which insults both their intelligence and the gravity of their decision to seek foreign military training.

2. The Phantom “Russian Assignment” and Internal Discord.

He recounts a meeting in Russia where OLF members approached him, but they could not agree on a common agenda for working inside Ethiopia. He claims he was later given a vague, “impossible” national assignment. This raises a fundamental question: if there was such profound disagreement on core strategy before undertaking major actions, why proceed? The attempt to blame subsequent failures on a pre-existing lack of consensus suggests a failure of leadership and collective decision-making, not merely the deceit of others.

3. The “Oromia Republic” Straw Man.

This is perhaps the most disingenuous claim. Gonfa asserts a foundational disagreement over the goal of an “Oromia Republic,” which he labels a “colonial agenda.” He claims this deadlock was irreconcilable. Yet, the public record shows that figures like General Kamal Galchu, in a VOA interview, spoke openly about the possibility of a republic after achieving liberation. Furthermore, the OLF’s own political programs have historically navigated the spectrum between self-determination and possible independence based on a popular referendum. To frame a central, debated political aspiration as a shocking, divisive “colonial” plot is a gross misrepresentation of the struggle’s own intellectual history, likely tailored for his current audience in Addis Ababa.

4, 5 & 7: The Shaebia Scapegoat and the Mystery of Betrayal.

Gonfa dedicates significant time to blaming Eritrea for their imprisonment and manipulating the OLA’s military wing. He describes a mysterious Colonel “Xamee” who allegedly controlled them. This narrative of total Eritrean control sits awkwardly with his other claims of internal OLA agency, such as the alleged refusal of some army units to follow orders in 2018. If the OLA was merely a puppet, how did it exercise such defiance? His testimony about Colonel Abebe (allegedly now a Brigadier General in the OLA) is particularly damaging but presented without context or corroboration. It creates a convenient fog where all failures can be attributed to a shadowy foreign hand, absolving internal leadership of critical misjudgments.

6. The Uncomfortable Transition from Refugee to Parliamentarian.

Gonfa’s personal journey—from an economic refugee with a Swedish passport to a member of parliament—is presented as a triumph of resilience. Yet, it unavoidably invites questions about the pathway from armed opposition to state legitimization. He speaks of the hardships of struggle, but for many watching, the stark contrast between the described suffering and his current official position underscores the complex, often ambiguous, transitions in Ethiopian political life, where former enemies can become state stakeholders.

8 & 9: Rewriting the Homecoming and the Gadaa Model.

He claims that upon returning to Ethiopia, they chose to work on national issues within the political system, respecting the existing OLF leadership. This sanitizes what many saw as a major split and a demobilization. His praise for the “Gadaa model” of conflict resolution, now being adopted in Amhara region, rings hollow. It appears less as a genuine endorsement of traditional systems and more as an endorsement of the federal government’s current policy of co-opting ethnic administrative models, a far cry from the Gadaa system’s principles of sovereignty and self-rule.

Conclusion: A Performance with a Purpose

General Hailu Gonfa’s interview is less a revelation and more a strategic repositioning. It is an effort to construct a personal and political narrative that reconciles a past of armed rebellion with a present of state accommodation. In doing so, it simplifies a multifaceted struggle into a story of foreign deception and internal error, draining it of its political substance and reducing it to a series of personal grievances and bad partnerships.

For the state, it is a useful narrative: the rebels were confused, controlled by Eritrea, and have now seen the light. For the still-active struggle, it is a warning about the power of state platforms to reshape history. For critical observers, it is a reminder that every testimony, especially those given in such loaded circumstances, must be read not just for what is said, but for the silences it cultivates and the interests it serves. The truth of the Oromo struggle, in all its sacrifice, complexity, and ongoing evolution, lies not in this single curated confession, but in the totality of its lived history, which is far messier, more principled, and more enduring than this interview suggests.

The Gedeo Daraaro Festival: A Celebration of Renewal and Justice

“Daraaro”: The Gedeo Festival of Renewal and its Modern Resonance

In the heart of Ethiopia’s capital, a celebration of profound cultural and spiritual significance is unfolding. The Gedeo people’s “Daraaro” festival—the annual marker of their transition from the old year to the new—is being observed in Addis Ababa with a solemnity and vibrancy that speaks to both its deep roots and its contemporary relevance.

Described as a festival of “gift, gratitude, and peace,” Daraaro is far more than a calendrical event. It is a living embodiment of a worldview. At its core, it is an act of communal reorientation: a time to present gifts (sita) to spiritual leaders (Abba Gada), expressing thanks for peace and success granted, and articulating collective hopes for health, security, and a bountiful harvest in the year ahead. This intertwining of the spiritual, the social, and the agricultural reveals a holistic philosophy where human well-being is inseparable from divine favor and environmental harmony.

What makes the current observance in Addis Ababa particularly noteworthy is its dual character. It is simultaneously an act of cultural preservation and a statement of modern identity. The inclusion of symposia and events detailing Gedeo history, culture, and language transforms the celebration into a platform for education and dialogue. It asserts that Gedeo heritage is not a relic of the past, but a vital, intellectual, and artistic tradition deserving of national recognition and understanding.

The festival’s official framing around the theme of “development for culture and tourism” is a significant and complex evolution. On one hand, it represents a strategic move to gain visibility and economic leverage within the Ethiopian state, which actively promotes cultural tourism. On the other, it risks commodifying a sacred tradition. The true test will be whether this external framing can remain a vessel for the festival’s intrinsic meanings of gratitude, peace, and social justice, rather than subsuming them.

Indeed, the commentary’s note that issues of “justice and the national system” are part of the discourse during Daraaro is crucial. For the Gedeo—a people with a distinct identity and a history intertwined with questions of land, resource rights, and administrative recognition—a festival of renewal is inevitably also a moment to reflect on societal structures. Prayers for a good harvest and communal safety are, in the modern context, also implicit commentaries on land tenure, economic equity, and political inclusion.

The most forward-looking aspect of the report is the work towards UNESCO recognition as intangible cultural heritage. This pursuit is a high-stakes endeavor. Success would provide a global shield for the festival, fostering preservation, research, and prestige. However, it must be navigated carefully to avoid fossilizing the tradition or divorcing it from the community that gives it life.

A Commentary: The Bridge of Daraaro

Daraaro, in its essence, builds a bridge. It bridges the old year and the new, the human and the divine, the individual and the community. Now, as celebrated in Addis Ababa, it builds another: a bridge between the particularity of Gedeo culture and the broader Ethiopian—and indeed global—conversation.

Its message of gratitude and peace is a universal one, yet it is delivered in the specific, potent vocabulary of Gedeo tradition. Its emphasis on social justice ties an ancient ritual to the most pressing contemporary debates. Its pursuit of UNESCO status places a local Ethiopian practice within an international framework of cultural value.

The celebration of Daraaro in the capital is thus a powerful symbol. It signifies that Ethiopia’s strength does not lie in a monolithic culture, but in the ability of its diverse nations and peoples to bring their unique, rich, and reflective traditions to the national table. It reminds us that a “new year” is not just a change of date, but an opportunity for societal recalibration—a time to offer gratitude, seek justice, and plant collective hopes for the future. In honoring Daraaro, we are reminded that some of the most vital frameworks for building a peaceful and prosperous society are not new political doctrines, but ancient festivals of renewal, patiently observed year after year.

Soil and Water Conservation: A Path to National Pride

A Green Future Takes Root: Soil and Water Conservation as a Legacy in Shawa Lixaa, Dirree Incinnii district.

In the heart of Shawa Lixaa, Dirree Incinnii district, a quiet but profound transformation is unfolding. Across multiple villages, a community-led initiative titled “Soil and Water Conservation Campaign for National Pride” has been underway for weeks. This is not a temporary project, but the steady, ongoing work of building a legacy.

The message from local leaders, like Administration and Natural Resources Office Head Obbo Tashoomaa Baqqalaa, is clear and compelling: “We are working to create a clean and fertile country for future generations.” This statement reframes environmental work from a technical chore into a moral and patriotic duty—a gift to the unborn.

The campaign’s objectives are a masterclass in integrated community development. It aims to:

- Enhance natural resource productivity and quality, turning existing assets into greater wealth.

- Combat soil erosion, directly addressing the creeping threat to Ethiopia’s agricultural backbone.

- Increase soil fertility and water availability, the twin pillars of food security and resilience.

What makes the effort in Dirree Incinnii particularly noteworthy is its stated methodology. Officials emphasize that the work is being carried out “at all levels and in an organized manner.” This suggests a holistic framework that moves beyond scattered plots of land. It implies coordination from household to village to district levels, ensuring the work is sustainable and scalable. The phrase “organized manner” points to planning, training, and community mobilization—the essential ingredients that separate a fleeting effort from a lasting movement.

Furthermore, the commitment to “participate and facilitate participation” reveals a crucial insight. The leadership understands their role is not just to direct, but to enable. True, lasting environmental stewardship cannot be imposed; it must be adopted, owned, and championed by the community itself. By actively facilitating broad-based involvement, the campaign sows the seeds of long-term stewardship alongside the physical conservation structures.

Commentary: Beyond Trenches and Terraces

This initiative in Shawa Lixaa represents more than the construction of physical soil bunds (misooma sululaa). It is the construction of a new environmental consciousness.

Firstly, it localizes a global crisis. Climate change and land degradation can feel abstract. By framing the work as creating a “clean and fertile country for our children,” it makes the imperative intimate, urgent, and actionable. It connects the trench dug today to the dinner table of tomorrow.

Secondly, it redefines “national pride.” Too often, national pride is linked solely to history, sport, or military achievement. Here, pride is being cultivated literally in the soil. The health of the land becomes a measure of collective responsibility and a source of dignity. A conserved landscape becomes a badge of honor, a “National Pride” earned through collective sweat and foresight.

Finally, it presents a model of proactive legacy building. In a world where future generations often inherit problems—pollution, debt, degraded ecosystems—this campaign is an act of intergenerational justice. It is about bequeathing an asset: productive, resilient land.

The challenge, as with all such endeavors, will be continuity. Will the structures be maintained? Will the participatory spirit endure beyond the campaign period? Yet, the foundational vision is precisely right. By tying soil and water conservation directly to national pride, community well-being, and the right of future generations to a fertile home, Obbo Tashoomaa and the people of Dirree Incinnii are not just conserving land. They are cultivating hope, responsibility, and a tangible, green legacy. Their work reminds us that the most profound patriotism can sometimes be found not in grand speeches, but in the quiet, determined act of planting a seed, or building a terrace, for a future one may never see.

Calgary’s Oromo Festivities: Heritage and Liberation Celebration

Oromo Community in Calgary Celebrates WBO Day and Amajjii Festival with Cultural Pride

28 January 2026, CALGARY, CANADA – The Oromo community in Calgary gathered this past weekend for a vibrant celebration of WBO Day (Waaqeffannaa, Boorana, and Oromo Heritage) and the traditional Amajjii festival. The event, held with great enthusiasm, served as both a cultural celebration and a reflection on the Oromo liberation struggle.

The festivities highlighted the spiritual and cultural significance of Amajjii, celebrated in accordance with the traditions of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). Speeches and presentations honored the legacy of past sacrifices in the Oromo freedom struggle, connecting the diaspora to ongoing narratives of resilience.

A powerful moment occurred as the Oromo flag was raised, drawing applause and reverence from the audience. Organizers used the gathering to educate the community about the enduring history and ongoing journey of the Oromo people’s quest for freedom.

“This event is about preserving our identity, honoring our heroes, and uniting our community across borders,” said one of the event’s organizers. “It is a day of both celebration and solemn remembrance.”

The celebration featured traditional Oromo music, dance, and poetry, transforming the venue in Calgary into a hub of cultural pride and collective memory. The event successfully reinforced cultural bonds for Oromos in diaspora while affirming their support for the cause of self-determination back home.