Challenges to PM Abiy Ahmed: Gedu’s Rebuttal on Tigray War

Senior Official Rebuts PM Abiy’s Claims, Alleges Cover-Up in Eritrean Role During Tigray War

[February 4, 2026] – In a scathing and meticulously detailed open letter to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Gedu Andargachew, a former high-ranking official, has issued a sharp rebuttal to the Prime Minister’s recent parliamentary statements, directly challenging the official narrative of Eritrea’s role in the Tigray war and accusing the administration of evading moral responsibility for the conflict’s atrocities.

The letter, dated January 27, 2015, Ethiopian Calendar, was prompted by the Prime Minister’s mention of Gedu by name during a parliamentary address concerning tensions with Eritrea on January 26, 2015, Ethiopian Calendar. Gedu states that this reference compelled him to “place the matter on the public record, without addition or subtraction,” offering a starkly different account of key wartime events.

Disputing the Official Eritrea Narrative

Gedu’s core contention challenges the timeline presented by the government. He asserts that Eritrean forces fought alongside the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) from the war’s outset until the Pretoria Agreement was finalized, contradicting the official line that their involvement was brief or contested.

He provides specific military details to support his claim, recalling a moment in the winter of 2013 E.C. (2020/2021 Gregorian) when Tigrayan forces advanced into the Amhara region. “We remember that the Eritrean army came as far as the Debretabor area and fought,” he writes. He further alleges that the ENDF and the Eritrean military conducted joint operations “in a manner resembling a single national army” until the peace deal was made public.

Alleging a Deliberate Cover-Up and Shift of Blame

The letter accuses PM Abiy of a pattern of deflecting responsibility for the war’s devastating human cost. Gedu expresses disappointment that instead of seeking forgiveness from the peoples of Tigray and Ethiopia, the Prime Minister chose to “simply provide explanations” and “try to find another party to blame.”

He argues this approach is not only a moral failure but also dangerous, stating it prevents the necessary lessons from being learned and “makes the recurrence of similar disasters possible.” Gedu directly links a range of national crises—the wars in Tigray and Oromia, alleged atrocities in Amhara, and conflicts in Benishangul-Gumuz—to what he calls the leadership’s “deficiency” and a flawed mindset that “cannot stay in power without conflict and war.”

Denying a Secret Mission to Eritrea

Gedu forcefully denies the Prime Minister’s insinuation that he was sent to Eritrea as a special envoy concerning the Tigray war. He clarifies he was removed from his post as Foreign Minister the day after the conflict began and states, “There has never been a suspicion that this issue was entrusted to me.”

He confirms a single trip to Asmara in early 2013 E.C. but describes a mission with entirely different objectives: to convey gratitude for Eritrea’s joint military cooperation, deliver a victory message regarding coordinated operations, and discuss mutual caution over mounting international “naming and shaming campaigns” related to human rights abuses.

Critically, Gedu claims that when he raised the international community’s demand for Eritrean troop withdrawal, PM Abiy explicitly instructed him not to request that Eritrea pull its forces out. “You warned me, ‘Do not at all ask them to withdraw your army,'” Gedu writes.

Revealing Contemptuous Remarks Toward Tigrayans

In the letter’s most explosive personal allegation, Gedu recounts a private meeting where he advised caution and the rapid establishment of civilian administration in Tigray to prevent future grievances. He claims PM Abiy dismissed these concerns with contemptuous rhetoric.

Gedu quotes the Prime Minister as allegedly stating: “Tigrayans will not rebel from now on; don’t think they can get up and fight seriously… we have crushed them so they cannot rise. Many people tell me ‘the people of Tigray, the people of Tigray’; how are the people of Tigray better than anyone? We have crushed them so they cannot rise. We will hit them even more; because the escape route is difficult, from now on the Tigray we know will not return.”

A Call for Accountability

The letter concludes not with personal grievances, but with a broader indictment of the administration’s governance. Gedu presents his detailed refutation as a necessary corrective to the historical record and an implicit call for a truthful accounting of the war’s origins, conduct, and consequences—an accounting he suggests is being actively avoided by the highest levels of government.

The Prime Minister’s office has not yet issued a public response to the allegations contained in the letter.

For more detail see the official Amharic letter of Gedu Andargachew

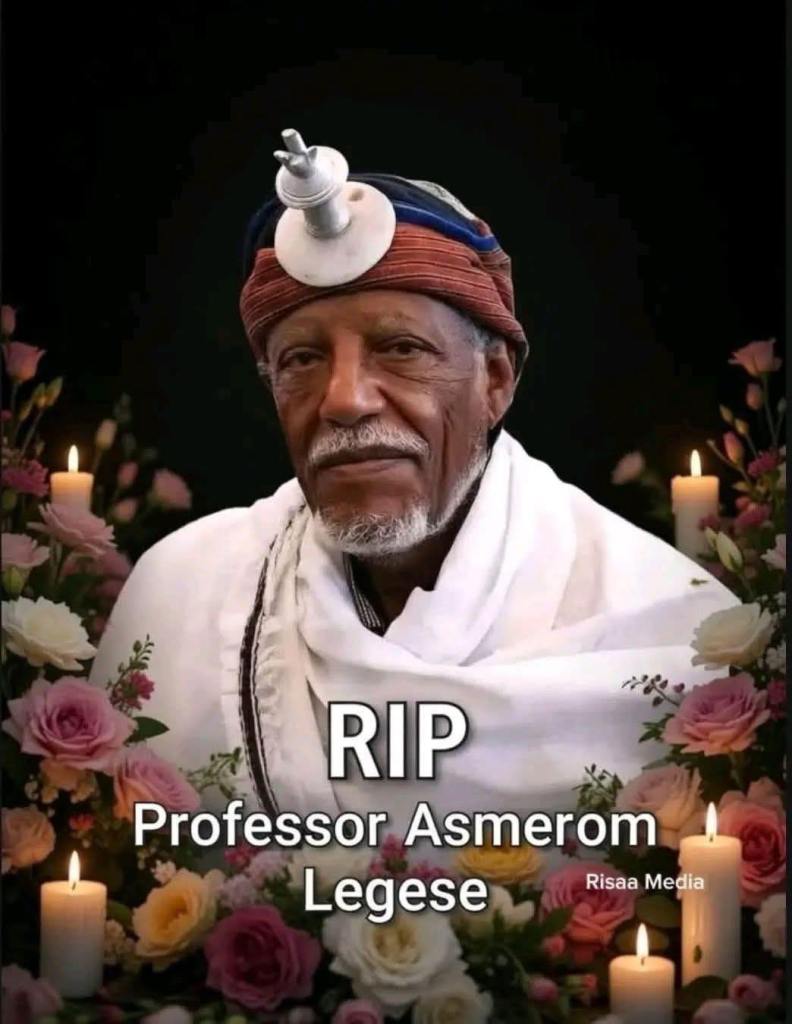

Borana University Mourns a Beacon of Indigenous Knowledge: Professor Asmarom Legesse

Borana University Mourns a Beacon of Indigenous Knowledge: Professor Asmarom Legesse

(Yabelo, Oromia – February 5, 2026) Borana University, an institution deeply embedded in the cultural landscape it studies, today announced its profound sorrow at the passing of Professor Asmarom Legesse, the preeminent anthropologist whose lifelong scholarship fundamentally defined and defended the indigenous democratic traditions of the Oromo people. The University’s tribute honors the scholar not only as an academic giant but as a “goota” (hero) for the Oromo people and for Africa.

In an official statement, the University highlighted Professor Legesse’s “lifelong dedication to understanding the complexities of Ethiopian society—especially the Gadaa system,” crediting him with leaving “an indelible mark on both the academic and cultural landscapes.” This acknowledgment carries special weight from an institution situated in the heart of the Borana community, whose traditions formed the bedrock of the professor’s most celebrated work.

The tribute detailed the pillars of his academic journey: a Harvard education, esteemed faculty positions at Boston University, Northwestern University, and Swarthmore College, and the groundbreaking field research that led to his seminal texts. His 1973 work, “Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society,” was cited as revolutionary for revealing “the innovative solutions indigenous societies developed to tackle the challenges of governance.”

It was his 2000 magnum opus, however, that solidified his legacy as the definitive voice on the subject. In “Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System,” Professor Legesse meticulously documented a system characterized by eight-year term limits for all leaders, a sophisticated separation of powers, and the Gumi assembly for public review—a structure that presented a centuries-old model of participatory democracy. “His insights challenged prevalent misconceptions about African governance,” the University noted, “showcasing the rich traditions and political innovations of the Oromo community.”

For his unparalleled contributions, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters from Addis Ababa University in 2018.

Perhaps the most powerful element of the University’s statement was its framing of his legacy beyond academia. By “intertwining the mechanics of the Gadaa system with the broader narrative of Oromo history and cosmology,” Professor Legesse was credited with fostering “a profound understanding of Oromo cultural identity.” It is for this work of preservation, interpretation, and transmission that he is declared “a hero—a goota—to the Oromo people and to Africa as a whole.”

Looking forward, Borana University management has called upon its students and faculty to honor his memory through “ongoing research and discourse on indigenous governance systems,” ensuring his foundational work continues to inspire new generations of scholars.

The entire university community extended its deepest condolences to Professor Legesse’s family, friends, and loved ones, mourning the loss of a true champion of Oromo culture and a guiding light in the study of African democracy.

About Borana University:

Located in Yabelo, Borana Zone, Oromia, Borana University is a public university committed to academic excellence, research, and community service, with a focus on promoting and preserving the rich cultural and environmental heritage of the region and beyond.

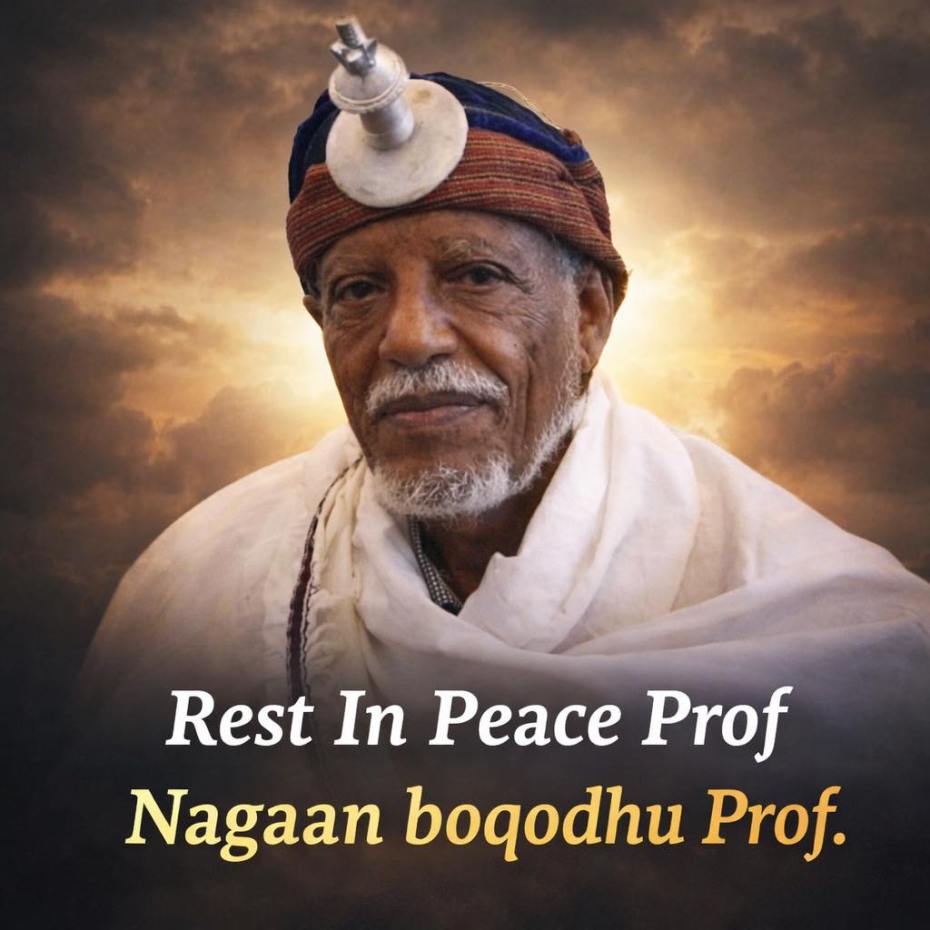

Remembering Prof. Asmerom Legesse: A Legacy of Oromo Scholarship

By Daandii Ragabaa

A Scholar Immortal: Prof. Asmerom Legesse’s Legacy Lives in the Hearts of a Nation

5 February 2026 – Across the globe, from the halls of academia to the living rooms of the diaspora, the Oromo community is united in a chorus of grief and profound gratitude. The passing of Professor Asmerom Legesse at the age of 94 is not merely the loss of a preeminent scholar; it is, as countless tributes attest, the departure of a cherished friend, a fearless intellectual warrior, and an adopted son whose life’s work became the definitive voice for Oromo history and democratic heritage.

The outpouring of personal reflections paints a vivid portrait of a man whose impact was both global and deeply intimate. Olaansaa Waaqumaa recalls a brief conversation seven years ago, where the professor’s conviction was unwavering. “Yes! It is absolutely possible,” he declared when asked if the Gadaa system could serve as a modern administrative framework. “The scholars and new generation must take this mantle, think critically about it, and bridge it with modern governance,” he advised, passing the torch to future generations.

This personal mentorship extended through his work. Scholar Luba Cheru notes how Professor Legesse’s 1973 seminal text, Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society, became an indispensable guide for her own decade-long research on the Irreecha festival. She reflects, “I never met him in person, but his work filled my mind.”

Ituu T. Soorii frames his legacy as an act of courageous resistance against historical erasure. “When the Ethiopian empire tried to erase Oromo existence, Professor Asmarom rose with courage to proclaim the undeniable truth,” they write, adding a poignant vision: “One day, in a free Oromiyaa, his statues will rise—not out of charity, but out of eternal gratitude.” Similarly, Habtamu Tesfaye Gemechu had earlier praised him as the scholar who shattered the conspiracy to obscure Oromo history, “revealing the naked truth of the Oromo to the world.”

Echoing this sentiment, Dejene Bikila calls him a “monumental figure” who served as a “bridge connecting the ancient wisdom of the Oromo people to the modern world.” This notion of the professor as a bridge is powerfully affirmed by Yadesa Bojia, who poses a defining question: “Did you ever meet an anthropologist… whose integrity was so deeply shaped by the culture and heritage he studied that the people he wrote about came to see him as one of their own? That is the story of Professor Asmerom Legesse.”

Formal institutions have also affirmed his unparalleled role. The Oromo Studies Association (OSA), which hosted him as a keynote speaker, stated his work “fundamentally reshaped the global understanding of African democracy.” Advocacy for Oromia and The Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau hailed him as a “steadfast guardian” of Oromo culture, whose research was vital for UNESCO’s 2016 inscription of the Gadaa system as Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Binimos Shemalis reiterates that his “groundbreaking and foundational work… moved [Oromo studies] beyond colonial-era misrepresentations.” Scholar Tokuma Chala Sarbesa details how his book Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System proved the Gadaa system was a sophisticated framework of law, power, and public participation, providing a “strong foundation for the Oromo people’s struggle for identity, freedom, and democracy.”

The most recent and significant political tribute came from Shimelis Abdisa, President of the Oromia Regional State, who stated, “The loss of a scholar like Prof. Asmarom Legesse is a great damage to our people. His voice has been a lasting institution among our people.” He affirmed that the professor’s seminal work proved democratic governance originated within the Oromo people long before it was sought from elsewhere.

Amidst the grief, voices like Leencoo Miidhaqsaa Badhaadhaa offer a philosophical perspective, noting the professor lived a full 94 years and achieved greatness in life. “He died a good death,” they write, suggesting the community should honor him not just with sorrow, but by learning from and adopting his teachings.

As Seenaa G-D Jimjimo eloquently summarizes, “His scholarship leaves behind not just a legacy for one community, but a gift to humanity.” While the physical presence of this “real giant,” as Anwar Kelil calls him, is gone, the consensus is clear: the intellectual and moral bridge he built is unshakable. His legacy, as Barii Milkeessaa simply states, ensures that while “the world has lost a great scholar… the Oromo people have lost a great sibling.”