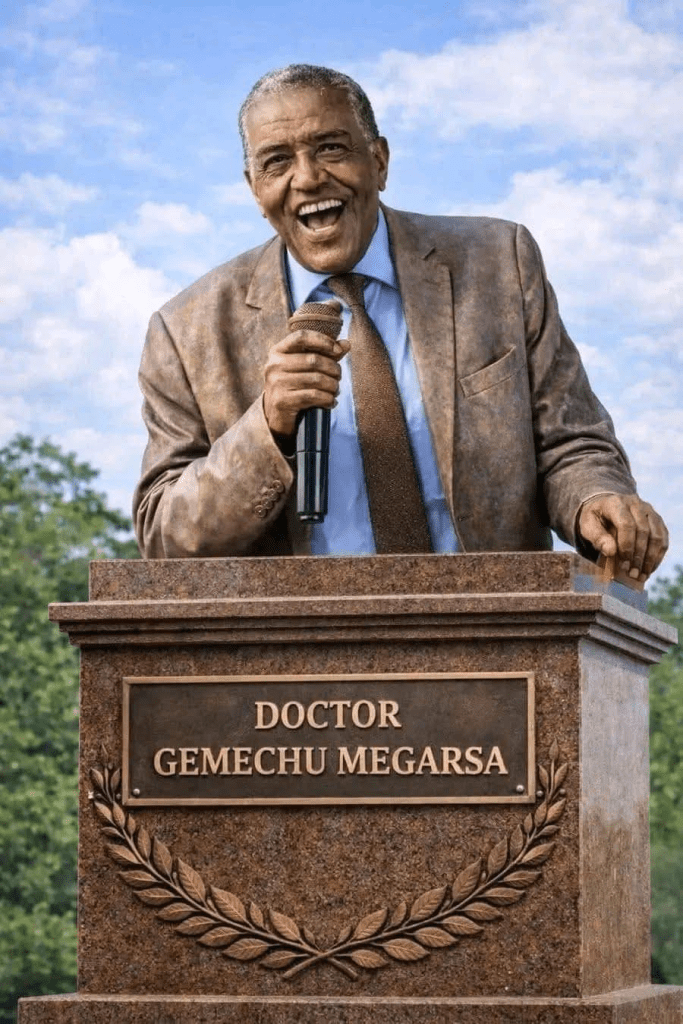

Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa: A Scholar’s Struggle in Oromia

A Scholar in Exile: The Plight of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa and a Community’s Anguish

A quiet crisis is unfolding in the heart of Oromia, one that speaks volumes about the precarious state of its intellectuals. Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa, a revered Oromo scholar, author, and elder, is reportedly in a dire situation, having lost his home and been forced to return to his birthplace in Qeellem Wallagga under difficult circumstances.

The news of Dr. Gammachuu’s troubles first circulated months ago but, as sources lament, “became a topic of discussion and then, while the Oromo community failed to find a solution, it was forgotten and left behind.” The issue was recently brought back to public attention through a poignant interview on Mo’aa Media, where the scholar himself confirmed the severity of his plight.

In the interview, Dr. Gammachuu shared a stark reality. After losing his house—reportedly sold to fund the publication of his scholarly work on Oromo history—he has returned to his ancestral land. “We have returned to our birthplace and are living there, farming our family’s land,” he stated, describing this turn as a significant hardship in his life. He revealed a history of being targeted, mentioning a prior expulsion from Addis Ababa University under the Derg regime.

His current predicament stems from a sacrifice for knowledge: “They sold their house to publish a book about the Oromo people,” he explained of the decision. He expressed frustration that people who know him seem unwilling to acknowledge his struggle, stating, “For the first time, I don’t know how this problem caught up with me, but I also don’t know how to be humiliated by a problem.”

The revelation has sparked profound concern and indignation within the Oromo community, both in Ethiopia and across the diaspora. The case of such an esteemed figure—a PhD holder who has contributed greatly to the preservation of Oromo history and culture—living without a stable home has become a powerful and troubling symbol.

The public reaction is crystallizing around urgent, critical questions directed at the Oromia Regional State government:

- Where is Oromo Wealth? Community members are asking, “The wealthy Oromos, where are they?” The question highlights a perceived disconnect between the region’s economic elite and the welfare of its most valuable intellectual assets.

- What is the Government’s Role? A more direct challenge is posed to the regional leadership: “The government that calls itself the government of the Oromo people spends money on festivals and various things. How is it that Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa, who has served the country with great distinction, has fallen through the cracks and is not provided a house?”

The situation of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa is no longer seen as a personal misfortune but as a test case. It tests the community’s commitment to honoring its elders and scholars, and it tests the regional government’s stated mission to uplift and protect the Oromo nation. His empty study is a silent indictment, and his return to the soil he has spent a lifetime documenting is a powerful, somber metaphor. The Oromo public now watches and waits to see if a solution will be found for one of its own, or if his struggle will remain an unanswered question in the ongoing narrative of Oromo self-determination.

The Crisis of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa in Oromia

A Scholar in Exile: The Plight of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa and a Community’s Anguish

A quiet crisis is unfolding in the heart of Oromia, one that speaks volumes about the precarious state of its intellectuals. Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa, a revered Oromo scholar, author, and elder, is reportedly in a dire situation, having lost his home and been forced to return to his birthplace in Qeellem Wallagga under difficult circumstances.

The news of Dr. Gammachuu’s troubles first circulated months ago but, as sources lament, “became a topic of discussion and then, while the Oromo community failed to find a solution, it was forgotten and left behind.” The issue was recently brought back to public attention through a poignant interview on Mo’aa Media, where the scholar himself confirmed the severity of his plight.

In the interview, Dr. Gammachuu shared a stark reality. After losing his house—reportedly sold to fund the publication of his scholarly work on Oromo history—he has returned to his ancestral land. “We have returned to our birthplace and are living there, farming our family’s land,” he stated, describing this turn as a significant hardship in his life. He revealed a history of being targeted, mentioning a prior expulsion from Addis Ababa University under the Derg regime.

His current predicament stems from a sacrifice for knowledge: “They sold their house to publish a book about the Oromo people,” he explained of the decision. He expressed frustration that people who know him seem unwilling to acknowledge his struggle, stating, “For the first time, I don’t know how this problem caught up with me, but I also don’t know how to be humiliated by a problem.”

The revelation has sparked profound concern and indignation within the Oromo community, both in Ethiopia and across the diaspora. The case of such an esteemed figure—a PhD holder who has contributed greatly to the preservation of Oromo history and culture—living without a stable home has become a powerful and troubling symbol.

The public reaction is crystallizing around urgent, critical questions directed at the Oromia Regional State government:

- Where is Oromo Wealth? Community members are asking, “The wealthy Oromos, where are they?” The question highlights a perceived disconnect between the region’s economic elite and the welfare of its most valuable intellectual assets.

- What is the Government’s Role? A more direct challenge is posed to the regional leadership: “The government that calls itself the government of the Oromo people spends money on festivals and various things. How is it that Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa, who has served the country with great distinction, has fallen through the cracks and is not provided a house?”

The situation of Dr. Gammachuu Magarsaa is no longer seen as a personal misfortune but as a test case. It tests the community’s commitment to honoring its elders and scholars, and it tests the regional government’s stated mission to uplift and protect the Oromo nation. His empty study is a silent indictment, and his return to the soil he has spent a lifetime documenting is a powerful, somber metaphor. The Oromo public now watches and waits to see if a solution will be found for one of its own, or if his struggle will remain an unanswered question in the ongoing narrative of Oromo self-determination.

Lessons from Oromo Liberation: The Pitfalls of Factionalism

A Commentary on Factionalism and Fidelity: Lessons from the Oromo Liberation Struggle

The history of any protracted liberation movement is often marked not only by external conflict but by the internal tremors of factionalism and dissent. The Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), as the vanguard of the Oromo national struggle for self-determination, has been no stranger to these internal fractures. A recurring narrative emerges across decades: groups breaking away in protest, creating a moment of internal chaos and heightened rhetoric, only to ultimately seek refuge or alignment with the very forces the movement was founded to oppose.

This pattern is worth examining. In 1998, a faction rebelled, sowing what is described as “chaos” within the struggle’s camp. Soon after, figures like the Biqilcha Sanyii group gathered and surrendered to the TPLF camp—the ruling party in Ethiopia that the OLF was fundamentally contesting. A decade later, in 2008, a group styling itself “Change” staged another revolt, creating a similar atmosphere of internal terror before fragmenting and, like the earlier Lichoo Bukuraa group, entering the TPLF fold.

These episodes, and the more recent schisms post-2018—such as the faction led by Jireenyaa Guddataa—follow a disturbingly familiar script. The dissidents frame all the struggles’ challenges and failures as creations of the OLF leadership itself. They present their rebellion as a necessary corrective, a purifying force. Yet, their trajectory often leads not to the renewal of the struggle, but to its weakening and, paradoxically, to the camp of the adversary.

This recurring fate points to a fundamental, painful lesson for liberation movements: The problem of struggle is not solved by rebellion against one’s own political home.

The immediate allure of schism is clear. It offers a clean break from perceived stagnation, a platform for new voices, and a dramatic claim to moral or strategic superiority. It channels frustration into action, even if that action is turned inward. However, when such rebellions are rooted primarily in opposition—in defining oneself against the parent organization rather than for a coherent, sustainable alternative—they often become politically orphaned. Lacking a deep, independent base and a clear path to victory, they become vulnerable to co-option or absorption by external powers eager to exploit divisions within their opposition.

The commentary concludes with a powerful, counterintuitive axiom: “The problem of struggle is solved by submission to one’s own values and principles, patience and determination to overcome it.”

This is not a call for blind obedience, but for a deeper, more difficult fidelity. It suggests that the solution to internal crisis lies not in fragmentation but in rigorous recommitment to the core values and principles that birthed the movement: self-determination, democratic practice, justice, and the primacy of the Oromo people’s cause. It calls for the patience to engage in internal reform, dialogue, and criticism without the poison of treachery. It demands the determination to endure hardship, strategic setbacks, and internal debate as part of the long march toward liberation.

The historical pattern within the OLF suggests that splits which are reactions, not revolutions—that are born of frustration without a foundational vision—ultimately serve to validate the resilience of the original struggle’s framework, even as they wound it. They become cautionary tales, reminding current and future generations that the most perilous terrain for a liberation movement is often not the battlefield ahead, but the divisive ground under its own feet. True strength, the narrative implies, is found not in the ease of walking away, but in the hard labor of staying, rebuilding, and holding fast to the principles that make the walk meaningful.