Ethiopia’s Strategic Crossroads: When Criticism Blurs the Line Between Government and Nation

By Maatii Sabaa

Feature News

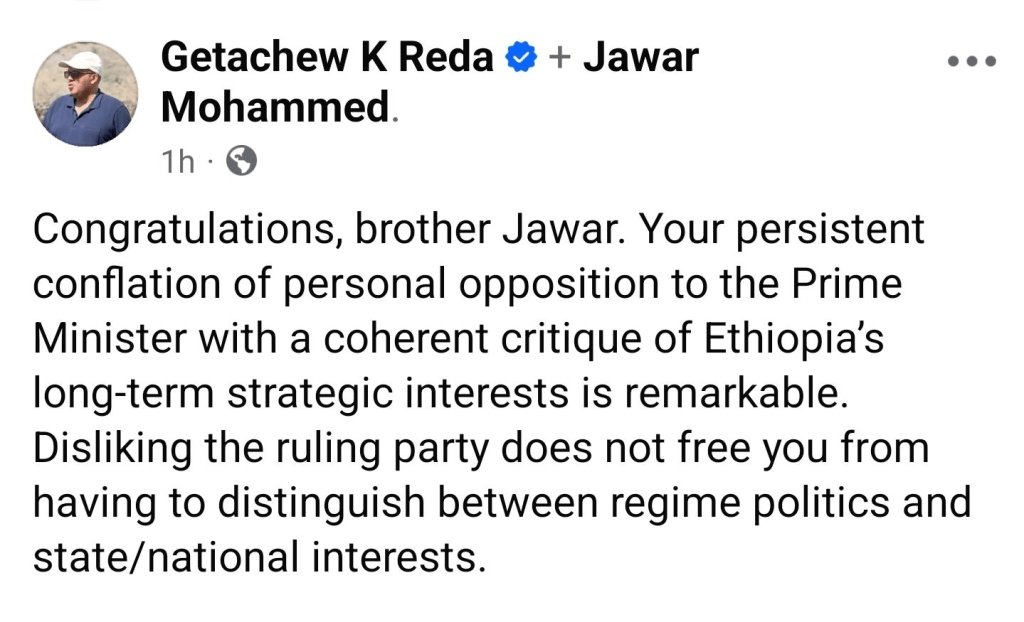

In the high-stakes arena of the Horn of Africa, where geopolitics shifts like tectonic plates beneath ancient soils, a troubling pattern has emerged in Ethiopia’s opposition discourse—one that increasingly conflates personal grievances against a sitting prime minister with the nation’s enduring strategic interests.

Over the past several days, Jawar Mohammed, once a close ally of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and now one of his most prominent critics, has launched a series of attacks against Ethiopia’s posture toward the deepening crisis in neighboring Sudan. His criticism, while occasionally resting on isolated facts, appears to systematically strip those facts of their broader strategic context—reducing complex national security calculations to evidence of government incompetence or malice.

The distinction being lost, critics argue, is one upon which stable democracies are built: the difference between the party in power and the state itself.

Facts Without Context: The Strategic Vacuum

Some of the reports circulated by Mohammed and his associates may be factually accurate in their narrowest sense. Ethiopia has indeed sought to protect its strategic interests amid Sudan’s collapse. It has engaged with actors on the ground. It has not adopted the posture of a passive observer.

Yet to present these moves as evidence of strategic folly—without reference to the regional power competition, Ethiopia’s existential stake in Sudanese stability, or the active interventions of other external actors—is to substitute selective outrage for sober analysis.

“The tragedy unfolding in Sudan is indeed exacerbated by foreign intervention,” one regional analyst noted, speaking on condition of anonymity. “But Ethiopia is hardly unique in pursuing its interests. What’s unique is Ethiopia’s vulnerability.”

No country in the region, and perhaps few beyond it, stands to lose more from a permanently destabilized Sudan. Ethiopia shares a 744-kilometer border with its northern neighbor. It hosts hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees. Its access to critical trade routes, its management of transboundary water resources, and its exposure to cross-border armed group proliferation are all directly implicated in Sudan’s trajectory.

Egypt and other regional actors are not neutral mediators. They have been actively shaping the conflict’s trajectory to favor preferred belligerents. To suggest that Ethiopia should operate as though this were not the case—or that acknowledging these realities somehow constitutes aggression—reflects what one foreign policy specialist described as “an aversion to the very language of national security.”

The Luxury of Abstraction

Mohammed positions himself as a politician-activist, a hybrid role that in theory could bridge grassroots mobilization and high-level policy engagement. But his recent posture suggests discomfort with the hard currency of statecraft: strategic interest, national security, geopolitical positioning.

In the Horn of Africa—a region defined by proxy competition, transboundary militant threats, and zero-sum maneuvering among rival states—such discomfort is not a virtue. It is a liability.

“States do not have the luxury of moral abstraction when core national interests are at stake,” said a former Ethiopian diplomat who requested anonymity to speak candidly. “You can critique how a government pursues those interests. You can propose alternative strategies. But to pretend that Ethiopia should have no strategy at all—or to frame every strategic move as evidence of malign intent simply because it originates from this prime minister—is not analysis. It’s partisan grievance dressed in policy language.”

The pattern has raised concerns among observers who note that Mohammed, widely believed to harbor ambitions for higher office, appears to be adopting what one analyst termed a “scorched-earth posture” not merely toward the Abiy administration but toward the Ethiopian state itself.

Governments Change. Geography Doesn’t.

This conflation carries implications beyond the immediate policy debates.

Governments are transient. Parties rise and fall. But strategic geography is stubborn. Ethiopia’s long-term national interests—its access to the sea, the security of its borders, the stability of its neighborhood, the viability of its water security arrangements—will outlast any single administration.

A credible political alternative, analysts argue, must demonstrate the capacity to distinguish between the party temporarily in power and the permanent interests of the nation. It must show that it can inherit the state without seeking to dismantle it.

“Thus far, Jawar has shown a near-pathological inability to make that distinction,” said Meheret Ayenew, a political scientist at Addis Ababa University. “The criticism never stops at the government. It bleeds into delegitimization of the state’s very right to defend its interests. That’s not opposition. That’s something else entirely.”

The Accountability Question

To be clear: critique of government policy is not only legitimate but essential. Ethiopia’s approach to the Sudan crisis, like any foreign policy posture, warrants scrutiny. Questions about coordination, consistency, and effectiveness are fair game.

But critique demands an alternative framework. What, precisely, should Ethiopia be doing differently? Should it abandon its engagement in Sudan entirely? Should it defer to Cairo’s preferred outcomes? Should it pretend that its national security is not implicated in the fate of its neighbor?

These questions, conspicuously absent from Mohammed’s recent broadsides, are the ones that distinguish serious opposition from performance.

Beyond the Immediate

The tragedy in Sudan has already claimed thousands of lives and displaced millions. For Ethiopia, the stakes are not abstract. They involve real security threats, real economic costs, and real humanitarian obligations that will persist regardless of who sits in the prime minister’s office in Addis Ababa.

In such moments, the distinction between government and state matters. A political culture that cannot sustain that distinction is one that struggles to produce durable alternatives—only perpetual opposition.

Whether Mohammed and his allies can evolve beyond this posture remains to be seen. But the clock is ticking. The region does not pause for Ethiopia to resolve its internal political debates.

And strategic interests, neglected or denied, have a way of asserting themselves regardless.