In the long and winding narrative of a people’s struggle for self-determination, certain figures become more than leaders; they become symbols. They embody a foundational moment, a spark that ignites an institution. For the Oromo nation, Mr. Hasan Alii Ibrahim, the first President of the Oromia Regional State, is precisely such a symbol. Today, as he concludes 27 years of exile and returns to his homeland, his legacy is not being revisited—it is being reclaimed. A powerful declaration echoes: “Seenaan Hasan Alii Hin Dagatamne!” – “The Legacy of Hasan Alii is Unquenchable!”

His presidency was born in a crucible of historic transition. Following the ratification of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) constitution on December 8, 1994, the monumental task began: to translate the promise of regional autonomy into a functioning government. Hasan Alii did not build Oromia alone. He stood shoulder-to-shoulder with a pioneering council—figures like Dr. Nagaso Gidada, Obbo Kumaa Dammaqsaa, Prof. Jamaal Abdulqaadir, and Hajji Musa Ababulgaa—who collectively deliberated, designed, and certified the birth of the Oromia Regional State. Among these architects, history records that Hasan Alii played the “lion’s share” in its establishment and organization.

His brief but pivotal tenure etched irreversible marks on Oromia’s identity. Three foundational acts stand as pillars of his enduring legacy:

1. The Affirmation of Finfinnee and Oromo Language: In a move of profound cultural and political significance, his administration legally established Finfinnee (Addis Ababa) as the capital of Oromia and Afan Oromo as the region’s working language. Furthermore, it mandated the Qubee (Latin) script for writing Oromo, ensuring its place in the region’s statutes and its future. This was not mere policy; it was an act of reclamation.

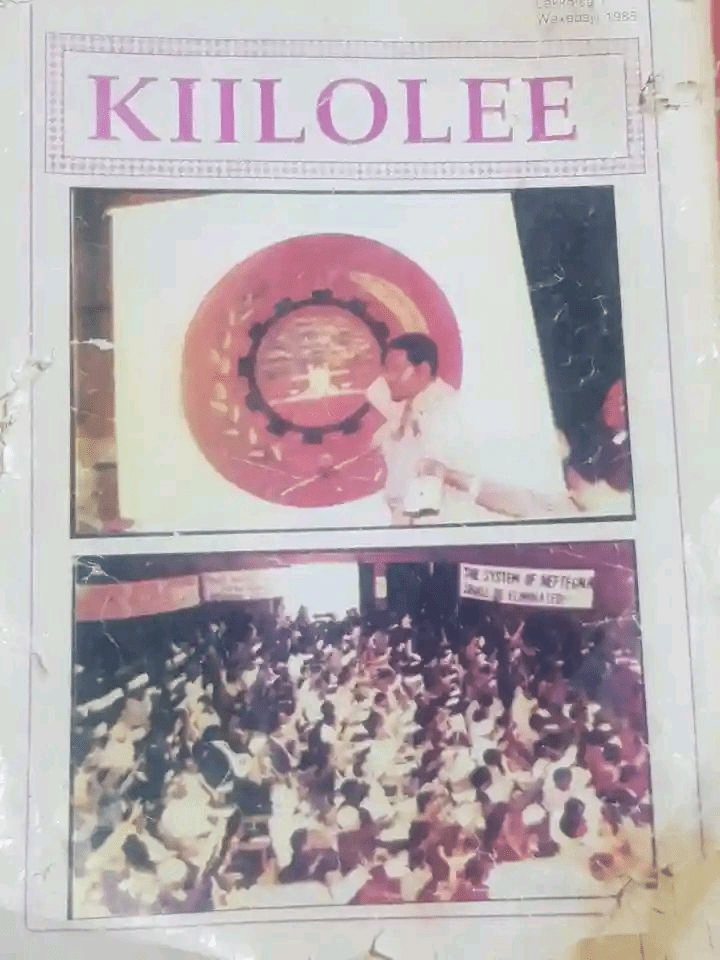

2. The First Seeds of a Literary Tradition: In 1993, shortly after the formation of the Oromia government, he oversaw a landmark moment: the publication of the region’s first document in the Qubee script, titled “Kiilolee” (“Steps” or “Foundations”). This was the tangible beginning of a modern Oromo literary and administrative tradition, the first official step in a long walk toward intellectual sovereignty.

3. Honoring the Martyrs of Calanqoo: Perhaps most poignantly, his leadership officially recognized and memorialized the sacrifices of the martyrs of Calanqoo, ensuring that the blood spilled in the struggle for Oromo rights would be woven into the fabric of the new state’s historical consciousness.

Today, the return of this “struggle hero, father of the struggle, and beloved leader” is more than a personal homecoming. It is a moment of national reflection. His return, facilitated by the invitation of current President Shimelis Abdisa, represents a symbolic bridging of generations—a recognition that the house of Oromia stands upon the foundation he helped pour.

The “unquenchable legacy” is not frozen in 1994. It lives on in every government document written in Qubee, in the cultural confidence of a generation that learned to read in its mother tongue, and in the very existence of Oromia as a political entity. Hasan Alii’s journey back is a powerful reminder that while pioneers may walk through wilderness, the flames they ignite—of identity, language, and self-rule—are designed to burn forever. His return is not just a conclusion to exile, but a reaffirmation that the foundational truths he fought for remain the bedrock upon which Oromia’s future must be built.