In the long and arduous struggle of the Oromo people for freedom and equality during the second half of the 20th century, a constellation of heroes emerged. Their sacrifices became the bedrock of the resistance. Among them stand the children of Baroo Tumsaa, whose contributions were carved not from a life of privilege, but from profound personal loss, relentless study, and a conscious choice to live not for themselves, but for their nation.

Four children of Baroo Tumsaa and his wife, Naasisee Cirrachoo—including the prominent Lubi Guddinaa Tumsaa and the focus of this tribute, Baroo Tumsaa himself—were forged in the crucible of the Oromo struggle, a movement cemented by thought, blood, and bone. This article seeks to honor this family’s immense legacy, with particular focus on the visionary life of Baroo Tumsaa.

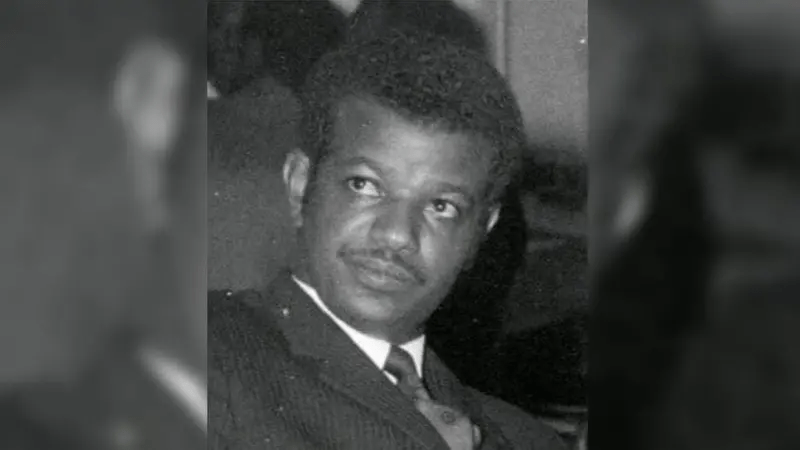

Baroo Tumsaa was born in 1938 in Boojjii Karkarroo, Western Oromia, and died in Harargee in 1978. Though his physical life was brief, his impact on the Oromo quest for equality was immeasurable. His is a story that transcends his lifetime, a truth that outlives death and continues to resonate today.

A Childhood of Loss and the Foundation of Resolve

Baroo, alongside his elder brother Lubi Guddinaa Tumsaa, his sister Raahel Tumsaa, and another brother, Nagaasaa Tumsaa, experienced early tragedy with the loss of their parents. This orphanhood thrust Baroo and his siblings into the care of their eldest brother, Lubi Guddinaa, planting seeds of resilience and interdependence that would later define his revolutionary dedication.

Education and the Awakening of Political Consciousness

After primary school in Naqamte, Baroo pursued his secondary education in Bishooftu. His academic journey took him to Haile Selassie I University (now Addis Ababa University’s Faculty of Pharmacy), where he graduated in 1966 as one of the first Oromo students to study pharmacy under the government’s sponsorship program.

It was here that his political consciousness blossomed. Alongside fellow students like the writer Baqqalaa Galataa, he began to engage with the ideas that would shape his future. Close comrades and fellow architects of the Oromo liberation movement, Dr. Diimaa Noggoo and Leencoo Lataa, remember him as a foundational figure. Dr. Diimaa recalls Baroo’s early leadership in student movements, including championing the slogan “Land to the Tiller” (Mareet Laaraashuu), a stance that foreshadowed his lifelong commitment to land justice.

Leencoo Lataa notes that Baroo was elected president of the university student union, a platform he used to build networks and discuss the Oromo cause. Even after Leencoo left for studies in America, Baroo remained, working with others to strengthen associations like the Macca and Tuulama Association, a key precursor to organized political struggle.

The Strategist: Building the Movement from the Shadows

Returning to Ethiopia, Baroo took a position at the Ministry of Community Health, a cover for his clandestine political work. His thesis, “Decentralization and Nation Building,” advocated for a federal Ethiopia where power was devolved to the regions—a visionary document that remains relevant in ongoing constitutional debates.

His brilliance lay in strategy and unity. Colleagues describe a man of profound political acumen, a “walking encyclopedia” on Ethiopian and global affairs. He understood that the Oromo struggle needed a structured vehicle. With Leencoo Lataa and Dr. Diimaa Noggoo, he spent two years meticulously drafting the political program for what would become the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF).

Recognizing the need for broader alliances, Baroo also helped establish Icaat (The Union of Ethiopian Oppressed Peoples), a coalition with southern nationalities. While some saw this as a tactical maneuver to build a wider front or even as a cover for the nascent OLF, it demonstrated his strategic mind and his belief that the Oromo struggle was interconnected with the liberation of all oppressed groups in Ethiopia.

His work was perilous. During the Derg regime, he operated under intense surveillance, using his government position and the guise of Icaat to covertly recruit, organize, and lay the groundwork for the OLF. He played a crucial role in supporting early Oromo media, including the first Afaan Oromo newspaper, Bariisaa, often intervening to secure the release of detained journalists like its founder, Maahdii Hamiid Muudee.

The Unifier: Weaving a Nation from Fragments

Perhaps Baroo Tumsaa’s greatest legacy was his unmatched ability to unite. He traversed Oromia, connecting people from all regions, religions, and social strata. He believed a liberation front must be built from Oromo from every corner, every faith.

“Without Baroo, the OLF could not have been born,” stated Leencoo Lataa emphatically. His comrade, Obbo Kabbadaa Qajeelaa, echoed this: “Baroo brought our people together from Wallagga to the East, from the North to the South. His ability to unite was decisive.”

Final Days and Enduring Impact

By 1977, as the Derg’s repression intensified, Baroo was forced underground in Harargee. There, he continued to politicize and train young Oromos. His life was cut short in April 1978 under circumstances his comrades describe as a tragic accident during a military engagement, unrelated to political or religious conflict.

His death was a devastating blow. “It took us ten years to produce new leadership,” Leencoo Lataa reflected. Baroo’s vision was clear: he believed in democracy and Oromo rights within a democratic Ethiopia. But he also held that if a just union was impossible, Oromia’s right to independence was a valid path.

A Personal Life Mirroring the Struggle

Baroo’s commitment extended to his personal choices. He married Warqinash Bultoo, from a central Oromia family, in a wedding ceremony that symbolically connected regions from Finfinnee to Baakkoo. They named their children with purpose: their first daughter, Naasisee, after Baroo’s mother; their son, Ejersa, after his grandmother. These choices were a subtle, profound act of preserving history and identity.

Conclusion: The Architect’s Blueprint

Baroo Tumsaa was more than a martyr. He was the chief architect of modern Oromo political organization—a strategist, a unifier, and a democratic visionary. His story is not one of a fiery battlefield death, but of the meticulous, courageous, and intellectually rigorous work of building a liberation movement from the ground up.

He worked with humility, fulfilled his promises, and dedicated his salary to support struggling comrades. As Dr. Diimaa Noggoo summarized, he was a man who knew how to collaborate, empower others, and see his commitments through to the end.

Today, as his widow and three children live in North America, the legacy of Baroo Tumsaa endures. It lives on in the very existence of the Oromo national movement he helped design and in the unfinished quest for the democratic, just, and free Oromia he dedicated his life to building. His was a life cut short, but the blueprint he drafted continues to guide the path forward.