In a quiet office at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada, a professor prepares her lectures on cultural identity and immigrant adaptation. Her story, however, is not one of detached academic theory. It is a living archive of resistance, a testament to the cost of truth-telling, and a continuous journey of making meaning from unimaginable fracture. Martha Kuwee Kumsa is more than a scholar; she is a siinqee feminist, a former prisoner of conscience, and an unyielding voice for the Oromo people—a living bridge between a brutal past, a turbulent present, and a determined future.

The Forging: Journalism, Terror, and the Search for a Husband

Martha’s life took its defining turn in the crucible of the Ethiopian Red Terror. Moving to Addis Ababa with dreams of engineering, she instead found a revolution, a shuttering of universities, and a calling to journalism. Her marriage to Leenco Lata, a founding intellectual of the Oromo Liberation Front, placed her at the epicenter of the Derg regime’s wrath. Her journalistic work—writing a column championing Oromo women’s culture and defiance—became an act of political courage.

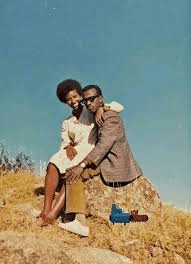

The personal and political catastrophes merged horrifically. After Leenco was seized for the fourth time and disappeared, Martha spent a year turning over corpses in the streets, a mother desperate for answers. She named her newborn daughter Goli—”terror”—an eternal testament to the era. Unknown to her, Leenco had survived and fled. In 1980, her own voice earned her a decade-long sentence in the regime’s gulags.

The Crucible: A Decade in the Dark

For nine years, Martha was detained without charge or trial in conditions of profound brutality. The description of her arrival—the stench, the disfigured bodies, the oozing wounds—is a scar upon the memory of anyone who hears it. She endured torture, including the savage falanga (foot whipping), yet her spirit refused to be extinguished. In a stunning act of intellectual resistance, she learned new languages and taught other prisoners, even the children of her jailers.

Her release in 1989, following international campaigns by PEN and Amnesty International that awarded her the Freedom to Write Award, was as abrupt as her capture. The world outside was alien, and the shadow of the past long. Her subsequent escape with her children through the forests to Kenya, and the miraculous, delayed reunion with a Leenco she believed dead, reads like an epic of survival.

The Reconstruction: Scholar, Advocate, Siinqee Feminist

In Canada, Martha rebuilt a life from its foundations. Earning her degrees in social work, she channeled her lived experience into academic rigor, becoming a professor specializing in the very forces that had shaped her: Oromo culture, identity, and diaspora. Her scholarship is not abstract; it is the systematization of a lived struggle.

Her activism never ceased. She became a powerful voice within PEN Canada and on global stages, advocating for human rights and free speech. Her siinqee feminism—rooted in the Oromo tradition of women’s sacred staves symbolizing law, protection, and collective power—informs her critique of both patriarchal oppression and reductive narratives about her people.

The Unflinching Voice: Confronting Narratives of Power

This perspective fueled her decisive intervention in late 2020 following the assassination of singer Hachalu Hundessa. In The Washington Post, with Bontu Galataa, she challenged the dominant media narrative that framed Oromos as mere perpetrators of violence. She detailed thousands of arrests, the raiding of Oromo media, and an internet blackout that created a vacuum filled by a monolithic, state-aligned story.

She argued this was an “Orwellian” inversion, reframing a historically marginalized people seeking justice as the architects of chaos. She specifically critiqued pan-Ethiopian feminists for broadly associating the Qeerroo (Oromo youth) and Qarree (young women) movements with violence, erasing their diversity, peaceful protest, and role in democratic change.

The Meaning-Maker: Between Past and Future

Martha Kuwee Kumsa’s life is a continuous project of “making meaning,” a term she engaged with during a collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario. From the Women’s Column in Bariisa to a Canadian university lectern, from a torture chamber to international op-eds, she has relentlessly woven the threads of personal trauma, cultural memory, and political analysis into a coherent, compelling narrative.

She is a guardian of history who refuses to let it be simplified or stolen. Her journey—from Dembidolo to a prison cell to a professor’s office—embodies a radical, unbroken hope: that truth, even when punished, can be reclaimed; that culture, even when suppressed, can be a foundation for identity; and that a voice, even after a decade of enforced silence, can emerge with unwavering clarity to challenge the stories of the powerful and speak for the silenced. In an age of manufactured narratives, her life is a testament to the enduring power of a story that is true.