NEWS FEATURE: The Shinniga Massacre and the Unhealed Wounds of the Oromo Struggle

A long-silenced, visceral wound in the memory of the Oromo liberation movement is being reopened—not in the pages of official history, but in the raw, contested space of social media debate. At the center is the Shinniga Massacre of April 15, 1980, a dark event where numerous Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and Western Bale Oromo (WBO) cadres were allegedly executed by Somali insurgents during the Ethio-Somali war.

The controversy was sparked when a pseudonymous Facebook user recently dismissed the tragedy as a “fabrication” (saaksiidha). They went further, casting similar doubt on the war injury of Bakar Waare, a military commander wounded in the Ali Changar war. When challenged with a counter-comment, the user responded not with evidence, but with a block—a modern act of erasure that echoes the historical silencing of the event itself.

“What I want to say,” explains a source close to the discussion, “is that people like this have completely adopted the Habesha (Ethiopian highland) historical narrative. When an Oromo speaks their truth, they attack you and demand proof. This is exactly the situation regarding the Shinile Massacre evidence.”

Testimony from the Killing Fields of Galeetti

The proof exists in the testimonies of the survivors. The massacre site, near Galeetti River, was orchestrated by a guide named Sulemaan, a former Somali military officer fluent in the Somali language. The harrowing account of one survivor, detailed in a poignant narrative now circulating, describes a betrayal after days of marching.

After being led to the Shinile area in the Ogaden, the Oromo cadres were disarmed by the Somali insurgents (Guuttada Labaad) under a pretext of safety. What followed was an interrogation laced with ethno-religious suspicion.

“They started questioning us,” the survivor recounts. “Since the others didn’t speak Somali, only Sulemaan and I answered. We told them, ‘We are Oromo and Muslim. We are not Habesha. We are going to the Somali government and we are not enemies of Somalis.’”

Their pleas fell on deaf ears. The insurgents fixated on the label “Habesha,” ignoring their Oromo and Muslim identity. Accused of being the “Oromo army of Ibsa Hordofa” and being held responsible for a past conflict near Gooroo Re’ee, the cadres were condemned.

A chaotic, brutal execution ensued. The survivors were lined up, and a Grad rocket launcher and nine Kalashnikovs were turned on them. “I also prepared myself to die,” the witness states. Miraculously, they survived by playing dead amidst the carnage, a chilling detail they attribute to the killers’ haste to loot the money found on the leaders.

Unanswered Questions and Leadership Scrutiny

The tragedy raises piercing questions about the OLF’s leadership decisions at the time. Why were the cadres led into such obvious peril? Analysis points to two critical failures:

- A Fatal Miscalculation: The OLF leadership is criticized for seeking a political solution through dialogue while failing to adequately assess the imminent danger, highlighting a strategic vulnerability.

- The Betrayal of a Guide: The belief that the guide, Sulemaan, could be trusted because he was paid a significant sum is seen as a catastrophic error in judgment.

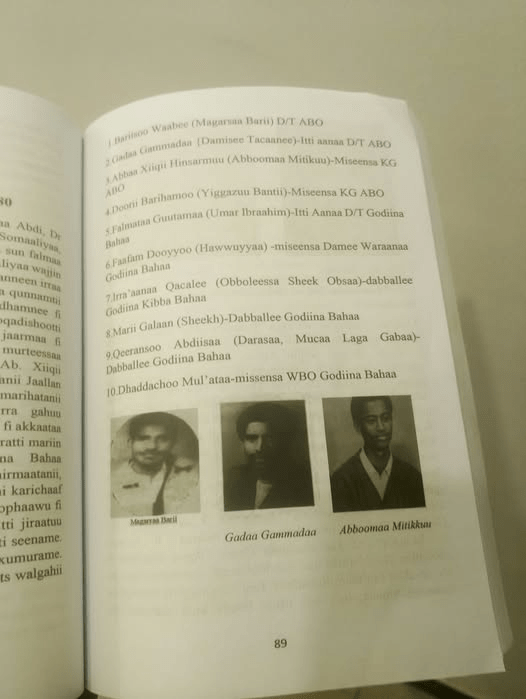

The Shinniga Massacre was a devastating blow in a period of profound loss for the OLF, following the death of strong leader Baro Tumsa in 1978 and the loss of ten other leaders in 1980.

Today, the struggle is not just to remember Shinniga, but to defend its memory from denial. As one commentator concluded, “We are reading the history of the OLF, and we have shared this part with you because you are discussing it. Thank you.” The implication is clear: to discuss Oromo history is to engage with its painful truths, its strategic failures, and the enduring testimonies of those who survived its darkest hours. The Shinniga Massacre remains a somber benchmark of betrayal and a testament to the terrible costs of a struggle where enemies could be on all sides.