In the quiet, determined spaces where movements are nurtured—in whispered conversations, in the careful preservation of a language, in the steadfast refusal to forget—there exists a powerful and often demanding creed: “The day of success comes in long-term patience.”

This is not a slogan of passivity, but a philosophy of deep-time struggle. It is an acknowledgment that the roots of true liberation grow slowly, often invisibly, through seasons of drought and frost before they break the surface. It is the understanding that history’s clock ticks to a rhythm far different from the frantic pace of news cycles or political gambits. For the Oromo people, engaged in a centuries-long quest for self-determination, this patience is not merely a virtue; it is the very bedrock of their resilience.

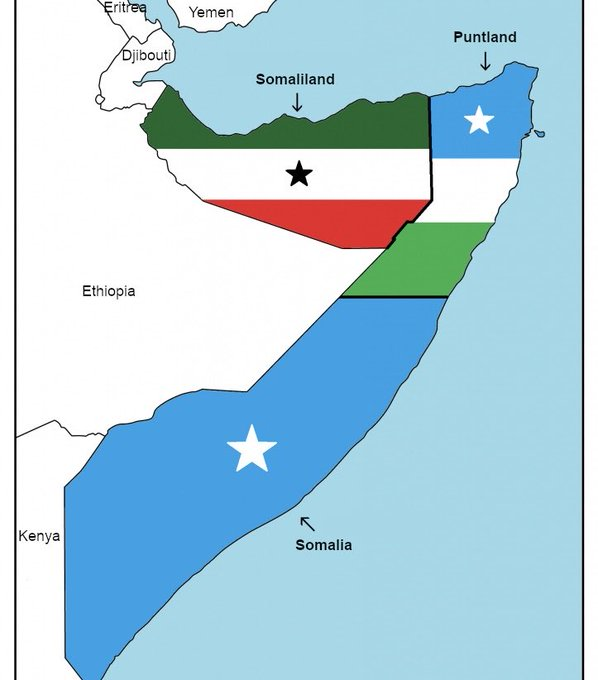

The statement carries a second, more specific hope, one that looks across the arid plains of the Horn of Africa for a precedent: “The day will come when the freedom of Oromo will succeed like that of Somaliland.”

This comparison is profoundly strategic. Somaliland stands as a unique anomaly in the modern world—a de facto nation that has built functioning democratic institutions, maintained relative stability, and sustained a cohesive national identity for over three decades, all without widespread international recognition. Its “success” is not defined by a seat at the United Nations, but by the tangible reality of peace, self-governance, and societal cohesion forged from the ashes of conflict. It is a testament to the power of internal consolidation and the unwavering assertion of sovereignty, even when the world is slow to acknowledge it.

For Oromo nationalists, the Somaliland example is both a mirror and a beacon. It mirrors their own experience of building robust cultural and administrative structures within the Oromia region, preserving the Gadaa system, and fostering a powerful sense of national identity against formidable pressures. It serves as a beacon because it demonstrates that a people’s political destiny can be shaped from the inside out, that legitimacy can be built first on the ground, in the hearts and minds of the people, long before it is stamped in diplomatic passports.

The path implied here is one of strategic patience. It is the patience to continue the meticulous work of nation-building in every sphere: in education that teaches true history, in the cultivation of economic self-reliance, in the strengthening of communal bonds, and in the unyielding, disciplined pursuit of political rights. It is the patience to understand that setbacks are not defeats but intervals in a much longer story.

This perspective does not discount the urgency of the present struggle or the severity of ongoing oppression. Instead, it frames that struggle within a generational context. It asks for a fortitude that can outlast regimes and outmaneuver immediate political crises, focusing on the ultimate horizon of freedom.

The day that dawns after such long-term patience is not merely a day of celebration, but a day of culmination. It is the day when the silent, steadfast work of decades—the cultural revival, the political mobilization, the sacrifices endured—coalesces into an undeniable reality. To believe that this day will come for Oromia, as it has for other nations who have held the line, is to invest in a future that is built not on hope alone, but on the daily, deliberate acts of a people cultivating their own liberation, one patient step at a time. The horizon may be unseen, but the direction is clear, and the journey, however long, is already underway.