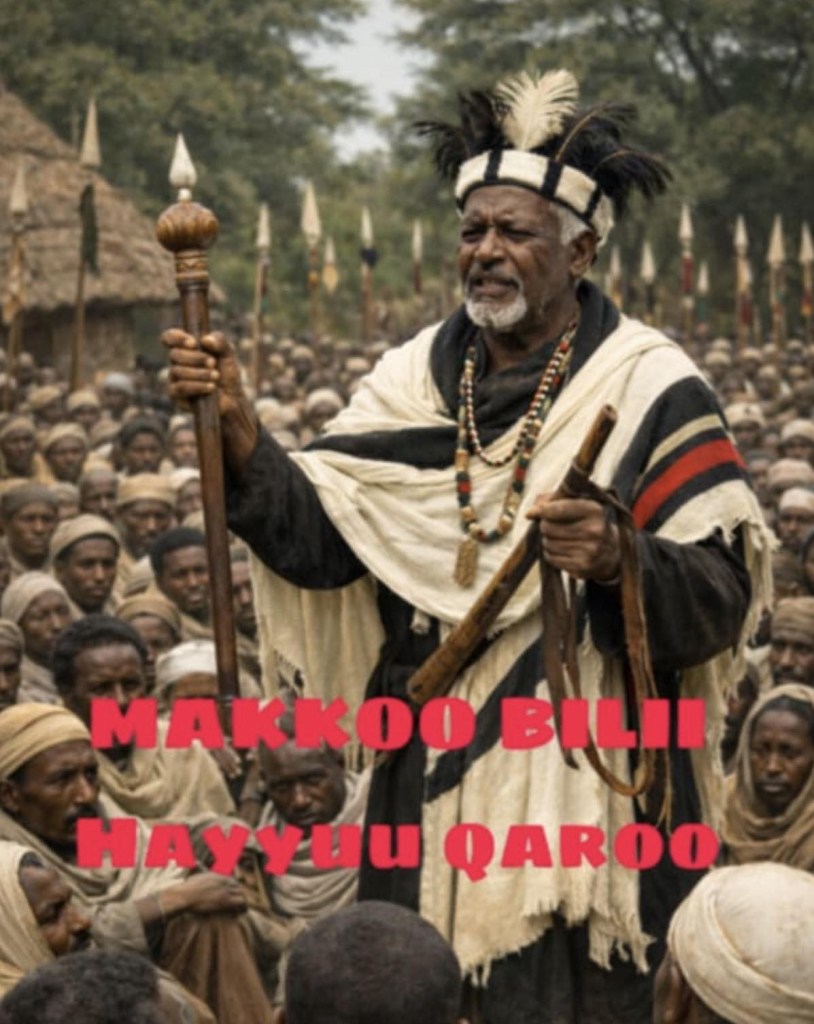

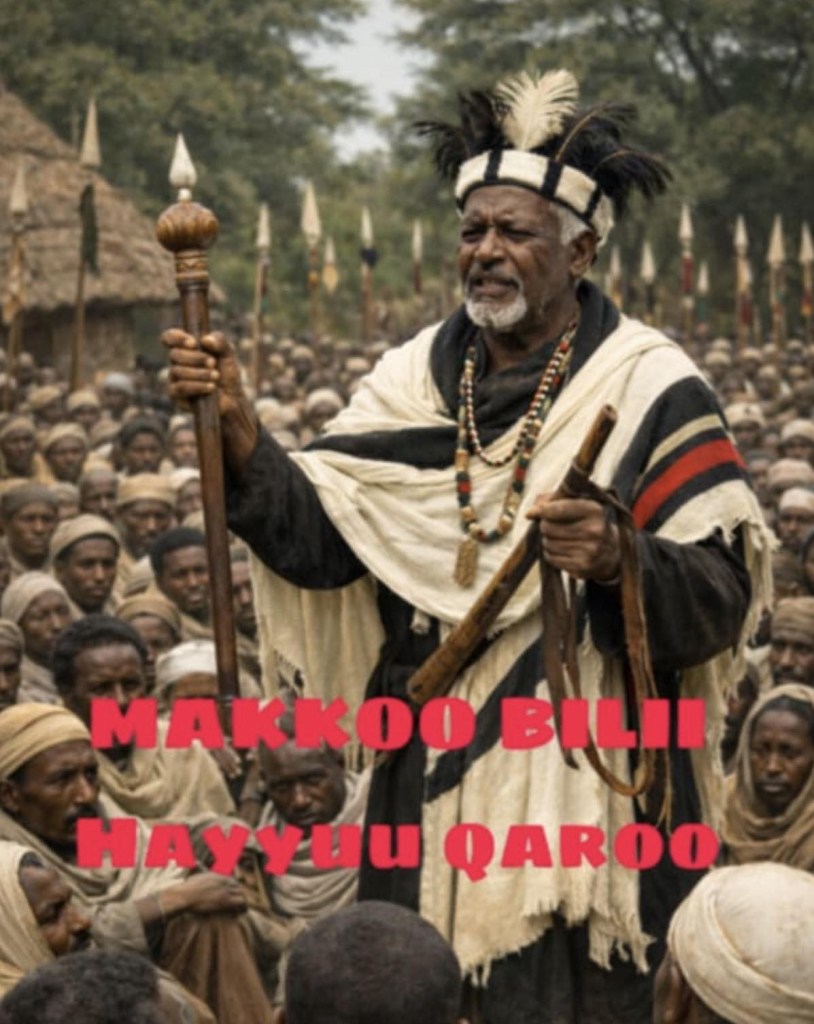

Feature Commentary: The Lost Legacy of Makkoo Bilii – The Unwritten Constitution

In the heart of Oromia, particularly among the Macca Oromo, a name echoes through the centuries not as a faint whisper of folklore, but as the potential architect of a foundational legal system. The name is Makkoo Bilii.

Historical fragments suggest Makkoo Bilii was born in the 16th century, with his life and leadership spanning roughly from the 1580s to around 1618. He is not merely remembered as a leader, but as a giddu galeessaa – a pivotal mediator, a powerful organizer, and a master strategist. His era was one of immense challenge, as the Oromo people expanded and solidified their presence, necessitating strong governance and unifying laws.

His crowning achievement, and the core of his fading legacy, is his role in codifying the Gadaa system for the Macca Oromo. In the wake of displacements and the struggle to reclaim rights, the Oromo established various assembly sites known as Caffees or Oddis. Makkoo Bilii is credited as the founder of the pivotal Caffee Odaa Bisil.

But he went beyond founding a meeting place. He is said to have promulgated a comprehensive legal code, a collection of over 65 distinct laws, which were inscribed at Sayyoo in Yemalogi, Qellem Wallagga. This was not merely administrative law; it was a constitution for his society, a framework for justice, governance, and social order.

The genius and democratic spirit of Makkoo Bilii’s system extended to his military. His army, thousands strong, was not organized along clan lines, but strictly according to the Gadaa class system. Soldiers were chosen and fought based on their Gadaa grade, transcending parochial loyalties for a unified Oromo identity. This principle was so embedded that places were even named after the Gadaa classes that controlled them (e.g., “Boojjii Birmajjii” – the land where the Birmajji Gadaa class halted).

His leadership bore tangible success. Oral histories speak of a golden age under Makkoo Bilii: a peaceful, self-governing Oromia that stretched, by some accounts, as far as present-day Tanzania.

And here lies the profound tragedy and the central question of this commentary: What happened to Makkoo Bilii’s laws?

The commentary suggests a stark answer: they were lost not to time, but to conquest and cultural subjugation. “Makkoo Bilii was born from an Oromo society that did not yet know how to preserve its heroes and its documents… his name and laws have been obscured.” His legal code, a potential written counterpart to the oral Gadaa tradition, did not survive the subsequent turbulent centuries of external pressure and the suppression of Oromo written expression.

While the resilient spirit of Gadaa endured orally, the specific, detailed constitution of Makkoo Bilii—a 16th-century legal framework that organized an army and named the land—faded into the realm of hushed reverence and fragmented memory.

This is more than a historical curiosity. It is a cultural wound. Imagine a society whose founding father and legal pioneer is a vague figure in its own education. The line “If only he had been born from another nation, his laws would be studied as formal education by generations today” is a poignant critique of the historical erasure faced by the Oromo people.

The legacy of Makkoo Bilii today is thus a duality:

- A Symbol of Peak Indigenous Organization: He represents the capability of the Oromo to develop complex, democratic, and effective systems of law and statecraft entirely from their own worldview.

- A Ghost of Lost Potential: He embodies the severing of a written legal tradition, a “what could have been” that asks painful questions about historical preservation, sovereignty, and the recovery of intellectual heritage.

The final call, “Let us be a generation that knows and defends its own strong history!” is the essential takeaway. The story of Makkoo Bilii is not just about honoring a hero. It is a urgent imperative for research, recovery, and reclamation. It is about searching for those 65 laws at Sayyoo, studying his strategies, and formally integrating his legacy into the narrative of Oromo—and indeed, Ethiopian and African—political thought.

His name means “Owner of the Season.” Perhaps now is the season for Makkoo Bilii to be truly owned, studied, and understood by the people whose laws he once so brilliantly forged.