In the shadow of volcanoes and sugar plantations, one of Africa’s oldest pastoral democracies faces extinction.

By Maatii Sabaa

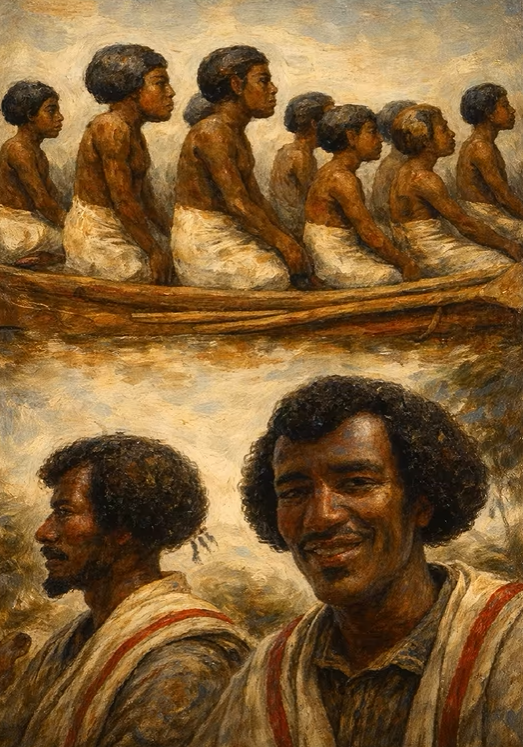

In the vast, volcanic landscapes of the Awash Valley, under the watchful presence of Mount Fentale, the Karrayyu Oromo move with their cattle across a land that has been theirs for centuries. To the casual observer, they might appear as just another pastoralist community surviving in a harsh environment. But to look closer is to witness something extraordinary: the living, breathing legacy of one of Africa’s most sophisticated indigenous civilizations—a civilization now on the brink of being erased.

The Karrayyu are among the oldest Cushitic-speaking groups of the Oromo nation. More than herders, they are widely recognized within Oromia as the guardians of a vanishing way of life, preserving social institutions, rituals, and a democratic governance system that have faded elsewhere. Alongside groups like the Borana and Guji, the Karrayyu represent the last custodians of a classical Oromo civilization. Yet their population has collapsed from an estimated 200,000 a century ago to perhaps fewer than 55,000 today. Their story is not one of natural decline, but of systematic dispossession.

A Land Dispossessed

The unmaking of the Karrayyu world began in earnest during the imperial expansions of the late 19th century, which dismantled indigenous governance and initiated a relentless process of land alienation. This process accelerated in the 20th century with the creation of the Awash National Park, which absorbed over 60% of their traditional territory, and the establishment of the Matahara Sugar Factory in the 1950s.

Over the last four decades alone, the Karrayyu have lost more than 70% of their ancestral lands to state farms and commercial plantations. Dikes built to protect sugar estates have altered the flow of the life-giving Awash River, while industrial pollution has turned sections of it into a toxic hazard. “The river used to give us life,” one elder explains. “Now it brings sickness to our children and our herds.”

Despite the intensive commercial exploitation of their homeland, the Fantalle district remains crippled by underdevelopment, with scant infrastructure, healthcare, or opportunity for the Karrayyu themselves.

The Gadaa System: Democracy in the Dust

At the heart of Karrayyu resilience is the Gadaa system, an intricate form of generational democracy that has governed their political, social, and spiritual life for centuries. It is a system of remarkable sophistication, with a complete cycle spanning 40 years and power rotating every eight.

Every Karrayyu man progresses through a series of nine age grades, from Dabballee (childhood) to Jaarsa (revered elder). By the time a man assumes the leadership grade of Luba at age 40, he has undergone 24 years of rigorous education in law, history, conflict resolution, and ecology.

Leadership is exercised through open assemblies called Chaffee, held under the sacred Odaa (sycamore) tree. Officials like the Abbaa Bokku (president) and Abbaa Seera (custodian of the law) serve strict eight-year terms. The assembly holds the power to remove leaders who fail their duties—a built-in check on power that predates modern democracies.

“Gadaa is not just politics,” says a Gadaa elder. “It is our constitution, our school, our court, and our moral compass. It teaches us to lead by serving and to see the land as a shared trust.”

Identity Marked on Skin and Soul

Karrayyu identity is woven into the very fabric of daily life. Women bear two horizontal facial marks on their cheeks; men style their hair in the distinctive Gunfura. These are not mere decorations but profound statements of belonging, linking the individual to lineage, territory, and collective memory. Their traditional monotheistic religion, Waaqeffata, centered on the supreme creator Waaqa, intertwines spirituality with a deep reverence for nature—a theology of balance, often misunderstood by outsiders as simple animism.

The Looming Silence

Today, the Karrayyu stand at a precipice. Squeezed by land grabs, ecological degradation, and political marginalization, their pastoral economy is under severe strain. Conflicts with neighboring groups over scarce water and grazing lands have intensified, fracturing old systems of reciprocity.

The threat is existential. If the Karrayyu way of life disappears, the world will lose more than a unique culture. It will lose a millennia-old model of social democracy, environmental stewardship, and community-based justice—a model that speaks powerfully to global crises of governance and sustainability.

A Question of Justice and Legacy

The struggle of the Karrayyu is a stark microcosm of the pressures facing indigenous pastoralists across Africa. It poses urgent questions: Who has the right to define progress? Does development require the destruction of ancient, sustainable civilizations?

“We are not against change,” another community leader reflects. “We are against our eradication. We are against being strangers in our own land.”

Preserving the Karrayyu civilization is not an act of nostalgia; it is an act of historical justice and intellectual necessity. It is about affirming that indigenous knowledge systems—honed over centuries of observation, adaptation, and democratic practice—hold vital keys to building more equitable and sustainable futures.

As the sun sets over the Awash Valley, casting long shadows from the sacred Odaa trees, the Karrayyu continue their ancient rhythms. Their fight is not just for survival, but for the right to remain who they are: the guardians of a civilization that has much to teach the world, if only the world would listen.

—

This article is based on historical analysis, field reports, and documentation from indigenous rights organizations. Names of elders have been omitted for their security.