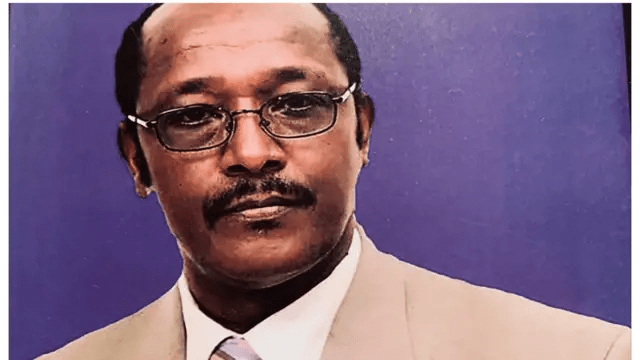

Feature Article: The Man Who Became “Abbaa Caalaa”: The Enduring Journey of a Revolutionary

In the annals of revolutionary struggle, names are not simply given; they are often forged in the fires of shared hardship, inside jokes, and sudden, defining moments of camaraderie. For one of the Oromo liberation movement’s stalwarts, his enduring name was born from a spontaneous challenge among friends in a Sudanese refugee camp in 1979.

“Abbaan Caaltuu geeraree, Abbaan Caalaa dhiisaaree!” (If Abbaa Caaltuu can roar, can Abbaa Caalaa stay silent?). With this defiant retort to a friend’s boast, the man then known as Abrahaam Lataa seized the moment, and a new identity was cemented. His friends, fellow fighters in the nascent Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), never let it go. From then on, he was Abbaa Caalaa Lataa—and the nickname outlived the moment, becoming the name history would remember.

This anecdote, shared by Abbaa Caalaa himself in a recent reflection, opens a window into the human spirit within a protracted political struggle. It reveals a story not just of ideological commitment, but of personal transformation, profound loss, and an unyielding belief in a cause that has defined a lifetime.

From “King of the Playground” to University Agitator

Born in the 1950s in Dambi Dolloo, Wallagga, Abbaa Caalaa’s early life was one of rural simplicity, herding livestock and playing with an inventive dominance he humorously recalls. His path took a pivotal turn at Addis Ababa University in the early 1970s, where he studied Economics. The campus was a crucible of political thought, and like many Oromo students of his generation, he was radicalized.

He immersed himself in the clandestine political discussions and writings that challenged the imperial and later the feudalistic structures of Ethiopia. “We would gather, debate, and disseminate ideas,” he recalls. The works of activists like Wallelign Mekonnen and Ibsaa Gutama were instrumental. For Abbaa Caalaa and his peers, the university was not just an academic center but the “epicenter” for organizing the foundational cells of what would become the OLF.

The Double Life: A Derg Official by Day, an OLF Organizer by Night

In a striking chapter of his life, Abbaa Caalaa, after a brief stint as a teacher, returned to Wallagga with a covert mission. Using a cover as a “Rural Development Expert” within the very Derg administration his movement sought to overthrow, he worked under high-ranking Derg officials like Abbiyyu Galata and Tesemma Nagari, who were secretly sympathetic to the Oromo cause.

“It was a dual life,” he explains. While publicly performing bureaucratic duties, he was privately building the OLF’s underground network. This dangerous game of shadows highlights the complex, layered nature of resistance during the Derg’s brutal reign.

The Horrors of War and the Resilience of Survival

The transition to armed struggle was marked by searing tragedy. As a commander in the western front, Abbaa Caalaa recounts the devastating Sagalee massacre of 1981, where a Derg force led by the notorious Nigusee Faantaa ambushed his comrades. His unit, led by Daawud Ibsaa, was almost wiped out by artillery fire.

“The day that group was hit by shells, we too would have perished if we had stayed with them,” he states somberly. He describes the immense grief and the subsequent fierce battles to regroup and retaliate. Daawud Ibsaa, captured and imprisoned for years, later escaped to rejoin the fight, a testament to the movement’s tenacity. Through these trials, Abbaa Caalaa rose to lead both the military and political wings of the OLF in the western region.

A Legacy of Awakening and a Warning for the Future

Now in his seventies and living in the United States, Abbaa Caalaa reflects on the journey from a time when speaking Oromo in Addis Ababa was an act of clandestine defiance to an era of profound Oromo political consciousness. “We used to speak Oromo loudly in the streets on purpose, to provoke thought, to make people ask questions,” he says. The primary goal of awakening Oromo identity, he believes, has been largely achieved.

Yet, his tone turns cautionary when discussing contemporary Ethiopia. The veteran revolutionary warns that the state cannot indefinitely suppress the fundamental quest for self-determination through force. “A government that sits down to talk with all stakeholders, including political prisoners, can find a solution,” he asserts. “Using force to answer demands will not bring a lasting solution.”

The Elder Statesman and the “Yuuba” Phase

Alongside his brother, the prominent Oromo politician Leencoo Lataa, Abbaa Caalaa now sees himself in the “Yuuba” stage of life—a Gadaa concept referring to elders who have stepped back from frontline politics to offer counsel and wisdom from behind the scenes. The two brothers, having dedicated their youth and middle age to the struggle, now debate, advise, and reflect.

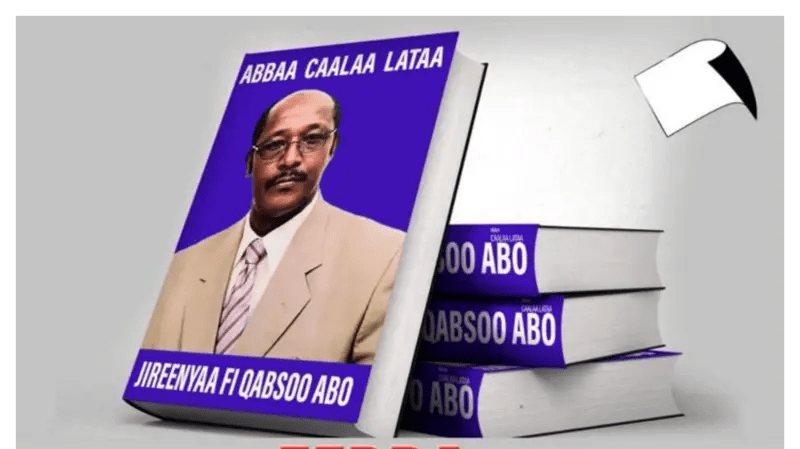

His final mission is to pass on the torch of memory. Having penned his memoir, “Jireenya fi Qabsoo ABO” (Life and the Struggle of the OLF), his driving concern is ensuring the sacrifices and lessons of his generation are not lost. “I have fulfilled my duty,” Abbaa Caalaa concludes. “I have done what I could. My final task is this book. If the Oromo struggle deviates, I will not be silent. How can I remain silent, seeing all that I have dedicated my life to?”

From a playful retort in a Sudanese camp to a lifetime of sacrifice, the story of Abbaa Caalaa Lataa is a microcosm of the Oromo struggle itself—a narrative of identity forged in resistance, tempered by unimaginable loss, and sustained by the unwavering hope that future generations will carry the cause forward, informed by the price paid by those who came before.