Feature Commentary: The Sycamore and the Plough – How a Sacred Oromo Assembly Ground is Being Erased

Under the sprawling, ancient branches of the Odaa Nabee sycamore, history doesn’t just live in stories; it is embedded in the earth. For generations of the Tuulama subgroup of the Oromo, this has been more than a tree. It is one of the Five Sacred Odaas, a living parliament, a court of law, and a church. Every eight years, as the Gadaa cycle turns, it transforms into the beating heart of their democracy—the place called Ardaa Jilaa, the ceremonial ground where power is transferred, laws are proclaimed, and the community is renewed.

But today, the sacred ground of Odaa Nabee tells a different, more urgent story. It is a case study in the slow, quiet erasure of indigenous heritage, not by conquest, but by encroachment.

The conflict is starkly modern, rooted in land deeds and ploughshares. The Ardaa Jilaa, a site of profound spiritual and political significance, has no formal legal boundary or protected status. “The ceremonial ground exists in history, but not in law,” explains Abba Gadaa Goobana Hoolaa. While the five great Odaa trees themselves have some recognition, the vital communal land surrounding them—the stage for the grand, eight-year gatherings—does not. Into this legal vacuum has moved the pressure for agricultural land.

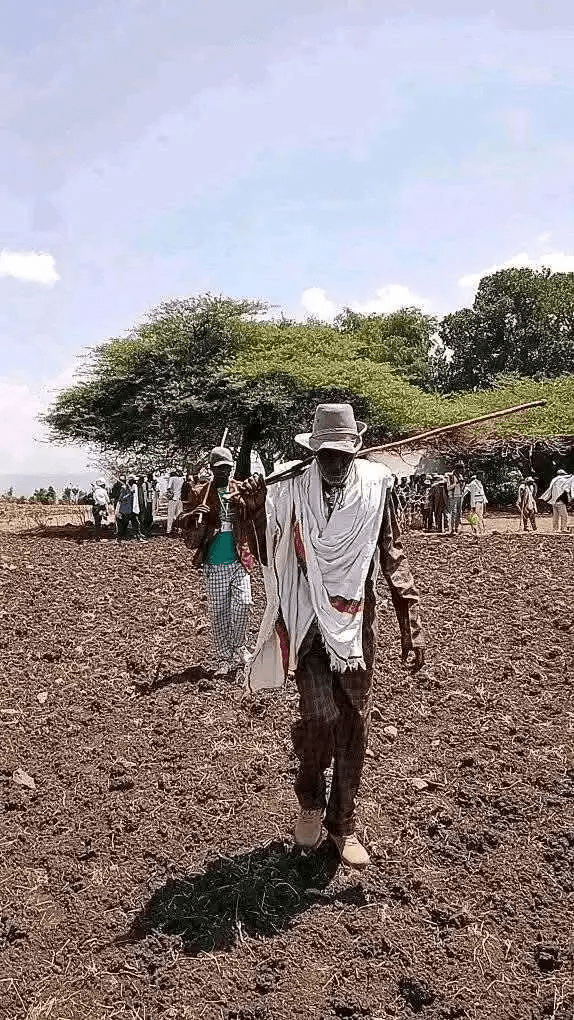

What was once a sacred clearing for thousands to assemble is now, in large part, a patchwork of ploughed fields. Farmers, citing their own need for livelihood and the lack of clear demarcation, have steadily expanded their plots onto the historic ground. The Odaa custodians describe a cycle of heartbreaking frustration: promises of protective fencing are made, a token foundation ditch is dug, and then all action ceases. The ploughing continues.

“We have been trying to get it preserved,” says Midhaksoo Gurmuu, Speaker of the Tuulama Gadaa Council. “But we have not been able. Now, this land is being farmed to its end.”

The implications are catastrophic for the cultural continuum. The Gadaa system operates on an intricate, unbroken eight-year calendar. The last full ceremony for the Michillee grade was held here. The next, for the Halchiisaa grade, is already on the horizon. The custodians voice a terrifying question: “When the Halchiisaa Gadaa assembly comes in eight years, what will happen? We don’t know.”

Their fear is that the physical space for their democracy will literally have been sown under. The ritual cannot simply be moved; its power derives from its specific, ancestral location. The erosion of the Ardaa Jilaa is, therefore, an attack on the very mechanism of Oromo self-governance and memory.

The response from local government has been described as a mix of bureaucratic failure and neglect. The land has been placed under the jurisdiction of the nearby town of Bishoftu, whose administration reportedly drafted a plan to demarcate only 8 of the site’s 13.2 hectares—a plan that has itself stalled. Requests for information from the local Culture and Tourism office go unanswered.

This story at Odaa Nabee is not isolated. Custodians report similar pressures on other Tuulama assembly sites at Dongora and Tumaati. It reveals a fundamental clash of values: the intangible, cyclical time of ritual and community versus the linear, economic time of agricultural expansion and private ownership.

The silent crisis at Odaa Nabee poses a monumental question: Can a nation preserve the living roots of its indigenous democracy in the face of modern development pressures? The Odaa tree itself still stands, a venerable witness. But if the ground where its people gather is lost, the tree becomes a monument to a severed tradition, rather than the centerpiece of a living one. The fight for Ardaa Jilaa is not just about saving a field; it is about ensuring that the next generation of leaders still has a sacred ground on which to stand and receive the staff of authority, as their ancestors have done for centuries.