Feature Commentary: Oda Bultum – The Lost Constitution Beneath the Sycamore

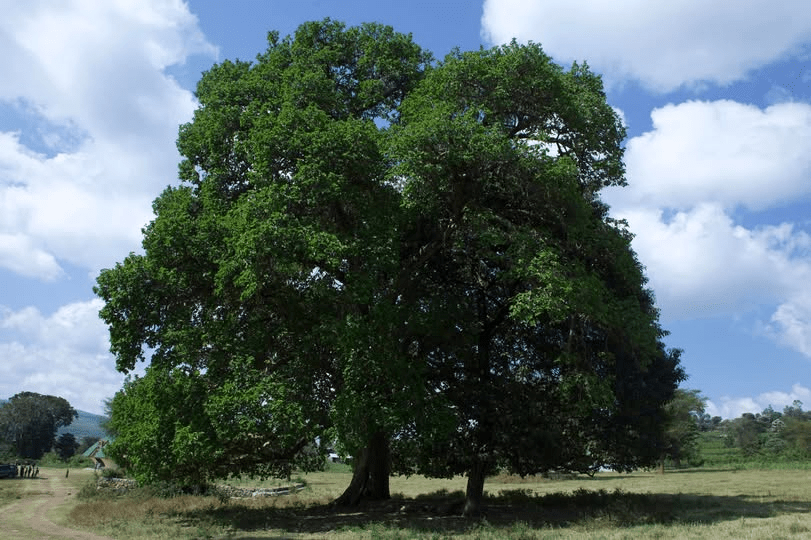

To stand at Oda Bultum today is to stand in a quiet field near Badesa, with the wind whispering through a surviving giant sycamore. To understand what it was, however, is to witness the ghost of a sophisticated state—a full-bodied democracy with a legislature, an executive, a judicial review body, and a detailed military chain of command, all humming under the open sky every eight years. This was not merely a “cultural site”; it was the capital of a nation without walls, and its story is a masterclass in the anatomy of indigenous governance and the tragedy of its erosion.

The Capitol Complex Under the Tree

The common description of Oda Bultum as a “Gadaa center” sells short its complexity. It functioned as a complete governmental campus. The main event was the Caffee Gadaa, a bicameral-seeming assembly. The elected Luba delegates, all over 40, formed a representative house. They debated, evaluated the outgoing administration, and under the moderation of the Abbaa Gadaa, crafted new laws. This was the legislative session.

But Oda Bultum’s process displayed a stunning sophistication with its built-in system of checks and balances. The laws written under the Oda tree did not simply take effect. They were sent two kilometers north to Garbii Darrabbaa, a congress of constitutional lawyers (Abbaa Heeraa). Here, each law was scrutinized for its constitutionality. Unconstitutional laws (Heer malee) were rejected. This was a dedicated judicial review body, separate from the executive Minister of Justice (Abbaa Seeraa).

From the legislature, power flowed to a meticulously elected executive. The Lubas elected the Shanan Gadaa—a five-minister cabinet covering War, Justice, Economy, Land, and Foreign Affairs—and their president, the Abbaa Bokkuu. This cabinet then governed for a strict, single eight-year term, advised by a Mana Hayyuu, a council of retired elders providing non-partisan wisdom. The structure intentionally prevented the consolidation of power, prioritizing cyclical renewal and collective wisdom over individual strongmen.

The Military & The Fatal Shift

Perhaps most revealing is the detailed military organization, the Raayyaa. Its structure—from a 9-person Saglii to the massive Raayyaa commanded by the Abbaa Duulaa—shows a society that could mobilize with breathtaking efficiency and discipline. The existence of the elite Qeeyroo unit underscores a professional military ethos.

This makes the site’s 19th-century decline not a fade-out, but a coup. The commentary notes the pivotal shift: the military council, Raabaa Dorii, grew dominant. The Abbaa Duulaa (Minister of War) usurped full authority. Concurrently, wealth replaced skill and wisdom as the criterion for leadership. This was the moment Oda Bultum’s essence died. The system designed to prevent autocracy and prioritize meritocracy was hollowed out from within, its balance of powers overturned by militarism and corruption. The “well-spring of Oromo wisdom” was poisoned.

The Echo in the Silence

The last full transfer of power here was in 2008. The physical site now faces the same threats as other sacred Odaas: encroachment, legal ambiguity, and the slow severing of practice from place. But Oda Bultum’s story poses a question larger than preservation: It challenges us to recognize what was lost.

This was not a primitive chieftaincy. It was a peer to other global democratic traditions, evolving in its own ecological and social context. Its collapse—first from internal decay and then from external invasion—represents the loss of a specific political technology, one built on term limits, meritocratic elections, bicameral deliberation, and constitutional review.

Today, Oda Bultum is a monument to a profound political possibility. The sycamore stands as a witness to a time when the state was a periodic gathering, leadership was a temporary service, and law was born from debate and ratified by scholars under a different tree. Its silent field echoes not just with lost rituals, but with the blueprints of a forgotten republic. To honor it is not merely to celebrate culture, but to grapple with the sophisticated governance it once anchored, and to ask what wisdom that “well-spring” might still hold for reimagining community and power today.