Feature Commentary

By Afendi Muteki

September 20, 2015 | Harar

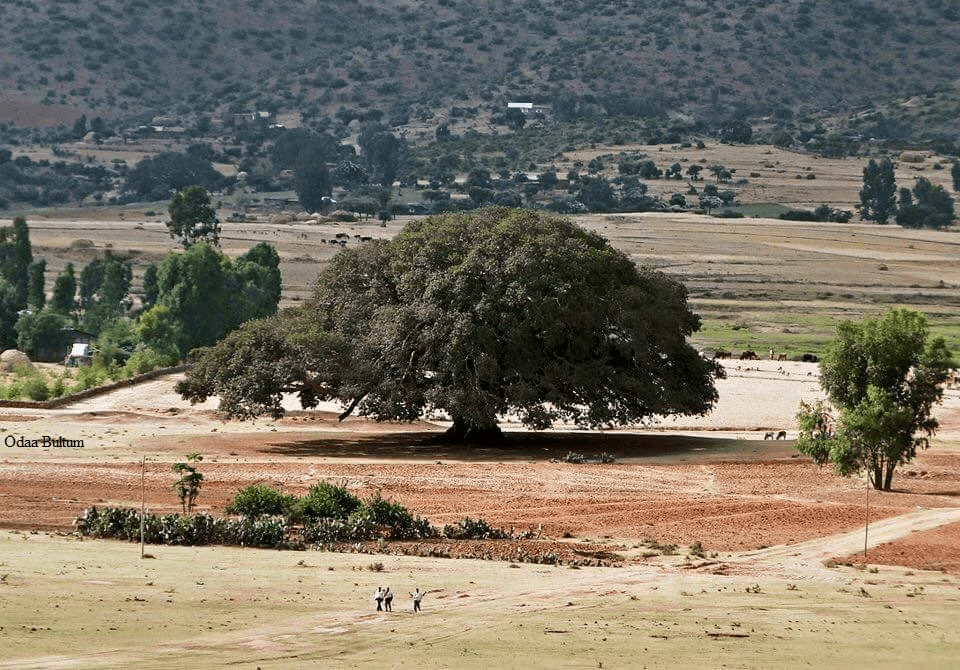

In the highlands of Eastern Oromia, beneath the shade of ancient acacias and in the halls of clan gatherings, a profound and ancient art form keeps the soul of a people alive. It is not written in books, nor is it performed on stage for mere entertainment. It is Mirriga — an elite, epic song tradition that serves as the living repository of Oromo law, history, and identity.

Among the Ittu, Karrayyu, and Afran Qalloo communities, Mirriga is not just a song; it is the sonic embodiment of wisdom. For the Ittu Oromo of Carcar in particular, it is inseparable from the legacy of Oda Bultum — one of the five sacred assembly trees of the Oromo Gadaa system. As they say:

Fooni nyaatti malee adurree ilkaan meetaa

Namaatu hinbeyne malee mirrigaa kheessi heera.

(The cat eats meat, yet its teeth remain silver.

Mirriga is law within, yet many do not understand.)

Mirriga is not for everyone. It is reserved for elders, leaders, and learned poets known as qondaala. It is performed only on significant occasions: during clan assemblies where laws are debated, or during the commemorative gatherings at Oda Bultum. In these spaces, Mirriga functions as both ritual and record — a melodic archive of social order.

The Poems That Hold a Nation

Mirriga poetry comes in two forms: the traditional and the non-traditional. The traditional poems are passed down orally and contain what the Ittu regard as their “golden constitution.” One such poem meticulously lists the symbolic items — eight bulls, eight spears, eight spoons, eight wells — used in rituals at Oda Bultum. Each number, each object, encodes part of a complex socio-political and spiritual system.

These verses map the clan structures: the four clans of the Galaan moiety who draft laws under the Oda tree, and the five clans of the Khura branch who deliberate under the Garbii Darrabbaa acacia. Through Mirriga, one doesn’t just hear a song — one witnesses the legislative and judicial architecture of a nation.

The Poet as Lawmaker, the Song as Court

Non-traditional Mirriga poems, composed by qondaala for specific events, test the poet’s ingenuity and reflect contemporary realities. One poignant example from the Haile Selassie era lamented:

Bakkan baanu nindhaqe waanin baanu nindhabe…

(I went where I said, but didn’t find what I wanted…

Except saying bow down, except saying pay tax…)

Here, Mirriga becomes a subtle vehicle of resistance and social commentary, proving its adaptability and enduring relevance.

Performance is dialogic and deeply communal. The qondaala begins with the call:

Dhagayi Dhageeffadhu (Hear me, and listen to me)

Guurii gurraa guuradhu (Take the dust from your ears).

The assembly responds with “hayyee” — “let it be” — or erupts with affirmations like “buli!” (long live!) and “kormoomi!” (be strong as a bull!). This is not a concert; it is a conversational liturgy of governance.

A Fading Echo in a Modern World?

Today, Mirriga remains a marker of cultural continuity. As the Ittu say:

Bakka guuzni oole darasiidhaan beekhani

Bakka gosti bulte ammo mirrigaadhaan beekhani

*(Where the *guuzaa* bird spent the day is known by the Darasii bird’s call*

Where the clan spent the night is known by the performance of Mirriga.)

Yet, this profound oral tradition faces the quiet threat of erosion. In an age of digital media and shifting social structures, the contexts for Mirriga are shrinking. The elders who hold its deepest verses are passing, and with them, volumes of unwritten history and jurisprudence.

Mirriga is more than folklore. It is the jurisprudence of the Oromo, sung into existence. To lose it would be to lose a constitution — not of paper, but of memory, melody, and moral order. Documenting Mirriga is not an academic exercise alone; it is an act of cultural preservation, a reclaiming of voice, and a testament to the fact that sometimes, the most powerful laws are not written—they are sung.