Feature Commentary: The Living Capital – How Me’ee Bokkoo Weaves Past, Present, and a $25 Million Future

Deep in the Guji highlands of southern Ethiopia, on a 958-hectare expanse of evergreen forest and open grassland, a nation is building its future by honoring the architecture of its past. This is Ardaa Jilaa Me’ee Bokkoo, the supreme ceremonial ground of the Guji Oromo, a site so sacred that for centuries it has been the sovereign, open-air capital of their Gadaa democracy. Today, it is the stage for a profound convergence: the recent, majestic transfer of the Baallii (symbol of Gadaa authority) is being met with the groundbreaking of a one-billion-birr ($25 million USD) cultural center. This is not a museum being built over a dead tradition. It is a permanent parliament rising beside a living one.

The Sacred Grove as Sovereign State

To call Me’ee Bokkoo a “cultural site” is akin to calling Westminster a nice old church. For the Guji Oromo, it is a geopolitical and spiritual heartland. Under the canopy of the sacred Me’ee tree (Ehretia cymosa), the Gumii Bokkoo—the general assembly—has convened for generations. Here, laws are drafted, ratified, and amended. Justice is dispensed. Peace is brokered. Most crucially, every eight years, the Baallii—the staff of authority—is transferred from one democratically elected Gadaa grade to the next in a ceremony that is the very engine of their cyclical governance.

The power of this place lies in its continuity. It is a polity without walls, where sovereignty is enacted through ritual and assembly. When Guji elders describe it as Lafa Woyyuu (a place of law and respect) and one of 423 such ritual centers, they are mapping a decentralized statehood, rooted in ecology and custom rather than in concrete and bureaucracy.

The $25 Million Handshake: Tradition Meets Institutional Will

The recent, colorful transfer of power from the Harmuufaa to the Roobalee Gadaa grade was a spectacular reaffirmation of this living system. Yet, this ancient ritual unfolded alongside a strikingly modern event: the signing of a one-billion-birr contract between the Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau and Walaabuu Construction.

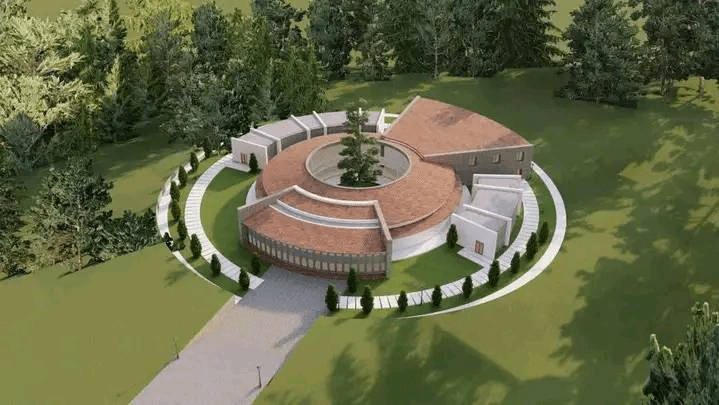

This is the critical new chapter. For decades, the custodians of Me’ee Bokkoo have advocated for its protection and development. They have watched with “worry,” as one elder put it, as their sacred ground was “filled with people” without the infrastructure to support its stature. The new contract is a direct response—a state-level recognition of indigenous sovereignty. It funds the construction of a “Cultural Center” (Galma Giddu Gala Aadaa), a complex designed to include research facilities, archives, and spaces where future generations can study the Gadaa system in situ. It is an investment not in fossilizing culture, but in empowering its continuous practice.

The Gadaa Network: Reuniting a People Across Time and Space

Perhaps the most powerful testament to Me’ee Bokkoo’s enduring role was not in a document, but in a reunion. During the recent ceremonies, a delegation from the Borana sub-group in the distant Aanaa Areeroo arrived after a 723-kilometer journey. Their elders spoke of a poignant historical echo: their ancestors, three centuries prior, had lived in the Babile and Jigjiga areas of eastern Oromia before dispersing. Their pilgrimage to Me’ee Bokkoo was a homecoming, a reconnection of branches separated by time and vast distance. As one attendee marveled, “Truly, the Gadaa system is one that brings together those separated by land.”

This moment encapsulates the project’s deeper purpose. The new cultural center is not just for the Guji. It is envisioned as a central node in a pan-Oromo network of sacred sites, a place where Uraagaa, Maattii, and Hookkuu Guji—and indeed, all Oromo—can reconnect with a shared constitutional heritage. It acknowledges that the Gadaa system’s strength lies in its intricate, interlinked web of Ardaa Jilaa across the nation.

Building on the Sacred, For the Future

The challenge is as delicate as it is monumental: to build a modern facility without violating the sanctity of the forest and the open ceremonial ground. The promise, as stated by officials, is to proceed with “cleanliness and speed,” respecting the elders and the ancient protocols. The center aims to be a tool for the tradition, not a replacement for it.

In an era where many indigenous systems are relegated to history books, Me’ee Bokkoo presents a radical alternative: a living democracy that is now receiving a state-backed infrastructure to ensure its survival and study. The one billion birr is more than a budget line; it is a bet that the future of Oromo identity and self-governance can be built upon the deepest, most sacred foundations of its past. As the concrete is poured for the new center, the ancient Me’ee tree will stand alongside it—a silent partner in a grand project to ensure the next eight-year assembly, and all that follow, have a home that honors their timeless gravity.