Feature Commentary: “Daaniyaa” Unbound—A Heritage Forged in Captivity, Resurrected in Print

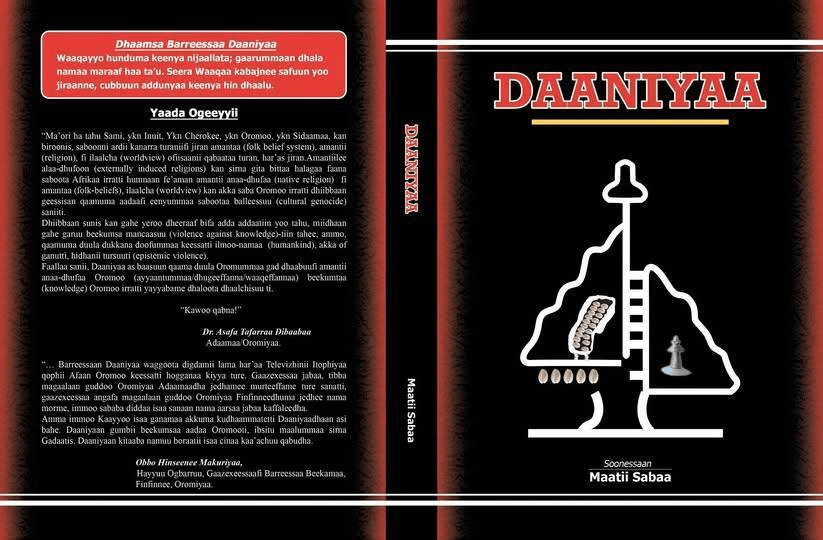

For generations, whispered in the echoes of old songs and the quiet yearning of elders, the Oromo community has held a space for a return. Not of a person, but of a story—a foundational text of memory and identity. That space now has a name, and it is back in triplicate. The release of the third edition of Daaniyaa is not merely a publishing event; it is a homecoming, a defiant act of cultural restoration being sold from a simple bookstore opposite the bus station in Finfinne.

The book’s journey from heart to hand is a map of modern Oromo resilience. The author’s revelation is as profound as the text itself: Daaniyaa was born in the heart but written in a prison cell. In that stark, restrictive environment, where the body was confined, the mind turned toward the most expansive of projects—the reclamation of a people’s soul. The choice of subject was both a deep philosophical strategy and a shrewd act of survival. Focusing on Oromo religion and culture was “a necessary and permissible path” within the walls, but it was pursued with an impermissible ambition: to unify, to strengthen, and to mobilize a nation.

This is where Daaniyaa transcends the page. It becomes a testament to the indestructible nature of heritage under siege. When political discourse was forbidden, cultural discourse became the vessel for liberation theology. When overt calls for unity were silenced, the intricate tapestry of shared history, spirituality, and the Gadaa system—the very bedrock of Oromo society—became the silent, unifying language. The author’s labor in that cell was an act of faith: that by grounding a people in the depth of their own past, they could find the compass for their future. It was a belief that knowing who you have been is the first, non-negotiable step in determining who you will be.

Now, the third edition on the shelves of Elellee Bookstore represents a new phase in this journey. The first edition may have been a spark, a proof of concept birthed from confinement. The third is a signal fire. Its availability in the heart of Finfinne is a quiet, powerful normalization. It says this heritage is not a secret to be guarded, but a legacy to be owned, studied, and debated in the open air. That a book contemplating a people’s essence for over six millennia is sold opposite a busy bus station is its own potent poetry—a deep, ancient current flowing alongside the everyday rhythms of modern life.

Daaniyaa thus operates on two inseparable levels. It is a vital scholarly and narrative contribution to understanding Oromo cosmology and social structure. But more urgently, it is a political artifact, a tool of intellectual sovereignty. It answers attempts at cultural erasure not with protest, but with profound, irrefutable detail. It offers a generation a mirror that reflects not fragmentation, but a coherent, majestic identity.

The long-awaited return is complete. But as the author knew in that prison cell, the return of the story is not the end. It is the beginning. It is an invitation, now widely available, for a people to gather around the hearth of their own history, to find in its ancient flames the warmth and the light to forge a unified path forward. The book is no longer just a testament written in captivity; it is a manual for liberation, sold at a bookstore, waiting to be carried home.