Feature Commentary: The “Trainee President” – How the Gadaa System Perfects Power Through Practice

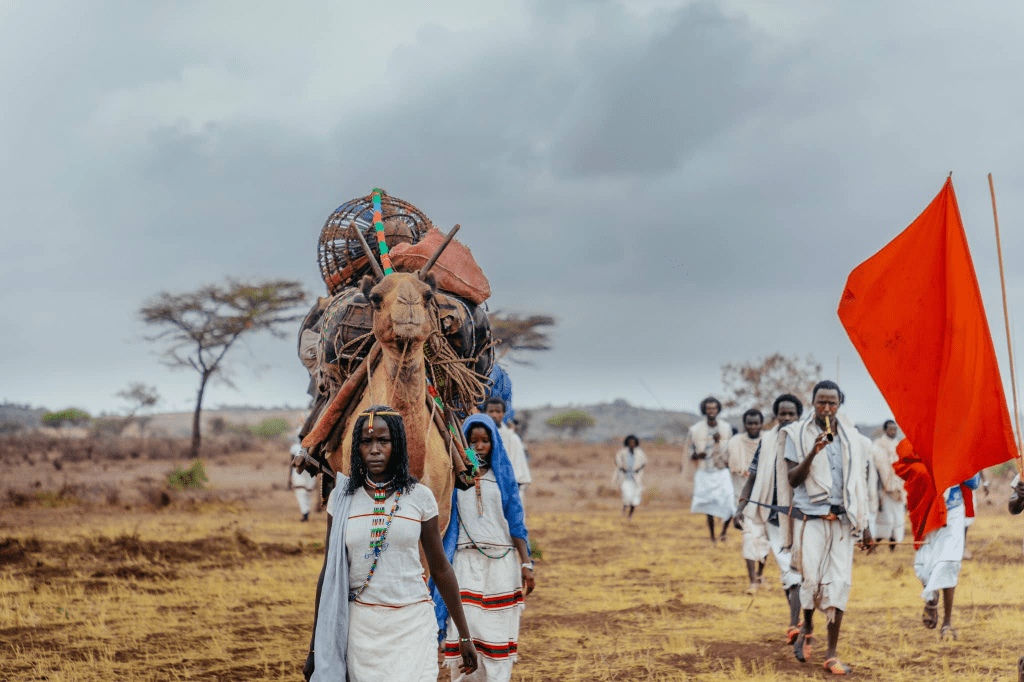

In Adama (Matahara), a city on the edge of the Great Rift Valley, a profound political experiment is in motion. Under the vast canopy of the Tarree Leedii ceremonial ground, the Michillee grade of the Karrayyuu Oromo is preparing not for a campaign rally, but for a constitutional handover. They are engaged in the final stages of Buttaa Qaluu – a meticulous, two-year period of “leadership training” where power is not seized, but patiently, systematically, and symbolically learned. This is the Gadaa system’s masterstroke: the creation of a “trainee president.”

At its core, Buttaa Qaluu is a mandatory political internship. The Michillee grade, which has held the Baallii (the scepter of authority) for eight years, is now obligated to mentor the incoming grade, Halchiisaa. This is not a ceremonial formality. As described by participants, it is a process where “the ruling grade cannot exercise full authority” for the final two years of its term. Instead, it must create space—a “shadow cabinet” period—where successors “learn the art of governing.”

The rules are strict and humbling. The trainee leaders (Halchiisaa) cannot travel widely, cannot independently convene major assemblies where the incumbent leaders are present, and must govern from the sidelines. They are, in essence, governing in a muted, observatory mode. “They hold the instruments of power but cannot sound them loudly,” the commentary notes. Their authority is “hidden” and their practice is discreet, ensuring a transfer based on observation and guided experience, not on sudden, untested assumption of command.

The genius of this system lies in its mitigation of three universal political pitfalls: inexperience, hubris, and destabilizing transition. By mandating a two-year apprenticeship, the Gadaa system ensures that by the time a grade assumes full power, its members are not novices. They have spent eight years in each previous grade (Dabballee, Foollee, Siidaa, Goobaa), and the final two years in direct, understudy observation of executive governance. Hubris is checked by the fact that the outgoing leaders are constitutionally required to share power before leaving, dismantling the cult of the indispensable leader. Finally, transition becomes a slow, overlapping process, not a sudden, cliff-edge event that invites chaos.

The role of the city of Adama and its administration in facilitating this ancient ritual is a striking example of modern-local synergy. The municipal government is not a passive bystander but an active enabler—organizing logistics, encouraging businesses to display Gadaa symbols, and treating the event as a major civic and cultural moment. This collaboration between a timeless indigenous system and a modern municipal structure underscores the Gadaa system’s enduring relevance as a viable, sophisticated model of governance, not a relic.

Thus, at Tarree Leedii, we witness more than a cultural festival. We see a working political academy. The Buttaa Qaluu is the Gadaa system’s built-in “transitional governance” protocol. It answers a critical question that bedevils modern states: how do you ensure new leaders are ready on day one? The Karrayyuu Oromo’s answer is elegant and ancient: you make them practice for two years under the watchful eyes of their predecessors. In doing so, they perfect a truth that eludes many political systems: true power is not in its fierce seizure, but in its wise and practiced transfer.